That leaving the EU would damage the overall economy is now being treated as more of a fact than a speculation. But those for Brexit argue that the rich will be negatively affected while the poor will benefit. This is not the case, write Holger Breinlich, Swati Dhingra, Thomas Sampson and John Van Reenen. Middle and low income households will be negatively affected as well the rich.

That leaving the EU would damage the overall economy is now being treated as more of a fact than a speculation. But those for Brexit argue that the rich will be negatively affected while the poor will benefit. This is not the case, write Holger Breinlich, Swati Dhingra, Thomas Sampson and John Van Reenen. Middle and low income households will be negatively affected as well the rich.

In recent days, pro-Brexiteers have been saying that leaving the EU may hurt the rich but it will help the poor. Although there is now a strong consensus that leaving the EU would damage the overall economy (HM Treasury, 2016; IFS, 2016; OECD, 2016; NIESR, 2016, The Guardian 28 May 2016) there has been almost no breakdown of what the effects would be on different types of people.

To tackle this, our new report examines the likely effect of Brexit on the prices of goods and services. We combined this with ONS (2012, 2014) data on what kind of things different households spent their money on. This enabled us to figure out who will win, and who will lose after Brexit.

We start by looking at the narrowest short run effects of trade (as in Dhingra et al, 2016a), before moving on to the more long-run effects. Trade costs will rise between the UK and the EU after Brexit as we will not have such complete access to the Single Market as we currently enjoy. Higher tariff and non-tariff barriers will mean higher prices.

The degree of price rise depends on the exact form of the deal we strike with the EU after Brexit. An ‘optimistic’ scenario is that we negotiate a high degree of Single Market access like Norway in the European Economic Area (EEA). However, this requires accepting all EU immigrants which seems to have been ruled out by the Leave campaign. Under a ‘pessimistic’ scenario where the UK were simply a member of the World Trade Organization, we would face much higher trade costs.

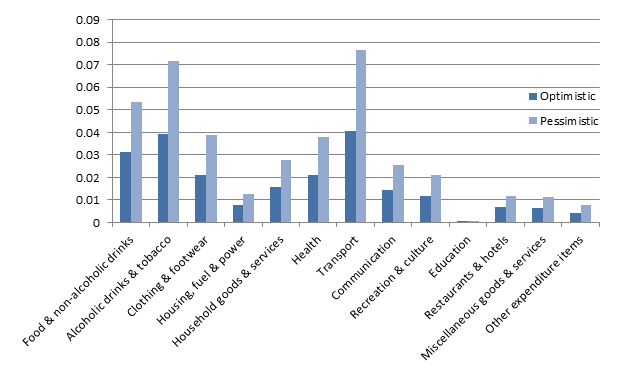

Figure 1 gives expected price increases across 13 product groups. Prices would go up most in transport (a price hike of between 4 and 7.5 per cent), alcohol (4 to 7 per cent), food (3 to 5 per cent) and clothing (2 to 4 per cent). These product groups rely a lot on imports, which would become more expensive due to tariffs and non-tariff barriers. By contrast, prices for services which are mainly provided locally would rise the least.

Figure 1: Price increases of goods and services after Brexit

Predicted price increases are based on the model by Dhingra et al (2016a)

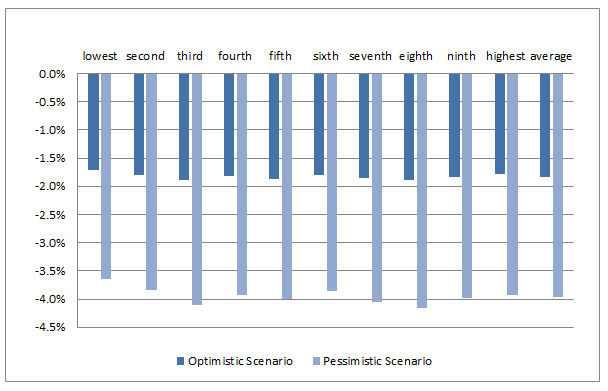

Since prices rise, the living standard of every income group would be lower after Brexit. We look at ten income groups, from the poorest 10 per cent to the richest 10 per cent of household income in Figure 2. This shows that the pain of Brexit is shared very democratically across all parts of the income distribution.

The income (not GDP) of the average UK household would drop by 1.8 per cent (£754) per year in our most ‘optimistic’ scenario. Income would fall by four per cent per year (£1,637) in our more realistic ‘pessimistic’ scenario. For the poorest tenth of households (the bottom decile), real income losses would be 1.7 to 3.6 per cent. For the richest households, the short-run losses would be 1.8 to 3.9 per cent. So the middle class would lose out the most, but only by a bit.

Figure 2: Real income losses by household income decile (%)

Predicted real income losses based on the model by Dhingra et al (2016a).

In the longer run, lower trade will have larger negative effects on income through lowering productivity. If we take account of these ‘dynamic effects’ the average household would lose between 6.1 and 13.5 per cent of their real incomes per year (£2,519 to £5,573) compared to remaining in the EU. The poorest group will be 5.7 to 12.5 per cent worse off and the richest will be 6 to 13.4 per cent worse off.

We summarise these results in the Table below, showing the loss in both proportionate terms and in terms of cash. Note that these are in terms of household income not GDP. Looking at specific households such as pensioners, families with children and single people, we find that the pain would also be widely shared. For example, even in the short run, pensioners would lose between 2 and 4 per cent of their income.

Summary of distributional effects of Brexit in cash terms

Notes: 2015-16 gross incomes figures projected from ONS (2012, 2014). Optimistic is the EEA/Norway scenario and Pessimistic is the WTO scenario. Dynamic model includes productivity effects of trade, static model does not.

Trade and wages

Could changing trade patterns have additional effects on cash wages? Our calculations focus on price changes and assume that nominal wage changes are proportional across income groups. This seems reasonable as the changes in prices across sectors are only weakly correlated with average earnings across sectors.

Economists for Brexit recommend that the UK unilaterally abolishes all trade barriers after leaving the EU. They claim that this will increase UK incomes. Their model predicts extremely large increases in wage inequality, which would mean that lower income groups would lose out much more from Brexit than we find. However, Dhingra et al show that their approach is riddled with errors as it ignores the most basic empirical facts, so their projected improvements in GDP will not materialise.

Immigration

The Leave campaign argues that EU immigration has had a negative effect on the UK labour market and that Brexit would help this by reducing migration. But as Wadsworth et al (2016) show, EU immigration has not increased unemployment or reduced the wages of the UK-born. Areas where EU immigration has risen the most have had no worse wage or job outcomes than other areas. They also demonstrate that on average the less skilled did not suffer major economic harm from EU immigration (Centre for European Reform, 2016). The problems in the labour market (and in public services for that matter) are due to the global financial crisis and austerity, not EU immigrants.

In fact, the most likely national impact of EU immigration on GDP per head is positive because immigrants are better educated and more likely to work than the UK born. So changes to immigration patterns will not materially alter the pattern of income losses reported here.

Conclusions

Economists consistently find that Brexit would lower real incomes in the UK. The cost of lower trade and foreign investment would not be outweighed by a reduction in the net fiscal transfer to other parts of the EU. The pain of Brexit will be evenly shared across the income distribution, with average losses of between 1.8 per cent (£754 per year) and 13.5 per cent (£5,573 per year).

When it comes to the pain from leaving the EU, it appears that no one would be spared.

___

Notes: This article is based on the paper Who Bears the Pain? How the costs of Brexit would be distributed across income groups and was originally published on LSE Business Review.

Holger Breinlich is Professor of International Economics at the University of Nottingham. He held previous positions at the University of Essex and the University of Mannheim. He is also a research associate at the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) and a research affiliate at the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

Holger Breinlich is Professor of International Economics at the University of Nottingham. He held previous positions at the University of Essex and the University of Mannheim. He is also a research associate at the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) and a research affiliate at the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

Swati Dhingra is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics at LSE. Before joining LSE, Swati completed a PhD at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and was a fellow at Princeton University.

Swati Dhingra is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics at LSE. Before joining LSE, Swati completed a PhD at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and was a fellow at Princeton University.

Thomas Sampson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at LSE. He holds a PhD in Economics from Harvard University and an MSc in Econometrics and Mathematical Economics (with distinction) from LSE.

Thomas Sampson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at LSE. He holds a PhD in Economics from Harvard University and an MSc in Econometrics and Mathematical Economics (with distinction) from LSE.

John Van Reenen is a Professor in the Department of Economics and Director of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. He received the European Economic Association’s Yrjö Jahnsson Award In 2009 (jointly with Fabrizio Zilibotti), as the best economist in Europe under the age of 45. In 2011 he was awarded the Arrow Prize for the best paper in the field of health economics.

John Van Reenen is a Professor in the Department of Economics and Director of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. He received the European Economic Association’s Yrjö Jahnsson Award In 2009 (jointly with Fabrizio Zilibotti), as the best economist in Europe under the age of 45. In 2011 he was awarded the Arrow Prize for the best paper in the field of health economics.

You say:

“Economists for Brexit recommend that the UK unilaterally abolishes all trade barriers after leaving the EU. They claim that this will increase UK incomes. Their model predicts extremely large increases in wage inequality, which would mean that lower income groups would lose out much more from Brexit than we find. However, Dhingra et al show that their approach is riddled with errors as it ignores the most basic empirical facts, so their projected improvements in GDP will not materialise.”

but, you cite:

“Although there is now a strong consensus that leaving the EU would damage the overall economy (HM Treasury, 2016; IFS, 2016; OECD, 2016; NIESR, 2016,”

without disclosing that these analyses have been criticised for lacking any grounding in macro-economic theory.

http://goo.gl/vXkOTd and http://goo.gl/bcs3ST

,” EU immigration has not increased unemployment or reduced the wages of the UK-born.”

In fact it has been shown that substantial depression of wages has been caused almost exclusively by EEA immigration:

Discussion Paper Series CDP No 22/13

Christian Dustmann and Tommaso Frattini

“By 2011, the percentage of natives with a degree had nearly doubled, to 21%, while the percentage of EEA and non-EEA immigrants had increased even further, to 32% and 38%, respectively19. Similarly, about one in two native born individuals fall into the “low education” category (defined as those who left full- time education before 17), while only one in five EEA immigrants and one in four non-EEA immigrants do so. EEA immigrants arrived since 2000 tend to include a slightly lower share of university graduates (although our measurement is imperfect because of problems coding foreign qualifications) but also a substantially lower share (around 10% in all years) of “low education” individuals than earlier immigrant cohorts from the same origin origin. Likewise, recent (arrived since 2000) nonEEA immigrants, although they show similar rates of university degrees as earlier immigrants, include a considerably lower share of “low education” individuals. These stark educational differences between immigrants and natives are not, however, reflected by wage differences, as we show in Table 2a: the median wages of natives and non-EEA immigrants are nearly the same, while the median wages for EEA immigrants are substantially below those of natives, by about 15% in 2011 …..

…….Interestingly, although in all years, recent immigrants, both EEA and non-EEA, have lower wages than earlier immigrants, they have similar or higher employment rates, especially in recent years. Recent EEA immigrants, in particular, have very high employment rates, just below 80% since the late 2000s. Conversely, over the same period, the employment rate of recent non-EEA immigrants has hovered consistently around 60%.”

“The common element in the consensus outside Economists for Brexit is that after Brexit, under the World Trade Organisation option, the UK continues to maintain protectionist tariffs and other trade barriers against the rest of the world, including the EU. By contrast, EfB assumes unilateral free trade after leaving the EU.”

“What has emerged from considering all these approaches used by different modelling groups is that they all assume post-Brexit, the pursuit of protectionist policies on imports by the UK. This reduction of the scope of free trade predictably would damage UK output and productivity whatever methodology is used.”

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jun/02/economists-brexit-eu-referendum-leave-recession-predictions-imf-treasury

Quite obviously pro-eu economic forecasts have intentionally excluded the WTO option of removing tariff barriers entirely which if reciprocated by the eu would keep prices the same in relation to eu goods and services and reduce prices in relation to non-eu goods and services.

The fact that pro-eu economic forecasts have failed to incorporate this option makes their overall forecast incomplete and so unsubstantive.

Wages are affected by immigration quite substantially.

https://fullfact.org/europe/2-junes-bbc-question-time-factchecked/