Alongside a suite of other constitutional reforms, the coalition government also plans to change electoral registration from household to individual registration. Toby S. James argues that this change will be expensive to implement and will actually lead to a decline in registration levels, something that the UK can ill afford given its current poor international ranking in this area.

Alongside a suite of other constitutional reforms, the coalition government also plans to change electoral registration from household to individual registration. Toby S. James argues that this change will be expensive to implement and will actually lead to a decline in registration levels, something that the UK can ill afford given its current poor international ranking in this area.

The Coalition government has sought to introduce rapid change across a wide range of policy areas. Electoral law has been amongst these. The Coalition introduced the first UKwide referendum since 1975 on the electoral system. It has torn up the rule book on how electoral boundaries are drawn with the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act. Elections for Police Commissioners are promised. No less important, but much less reported on, are the changes that are being proposed to electoral administration in the government’s white paper, published in June. These are the most dramatic changes since the foundations were last laid in the Representation of the People Act 1918.

The headline changes are that registration will become an individual rather than a household basis. Whereas a ‘head of household’ completes a registration form for all residents at a property, each individual will now have to complete a form themselves. They will also have to provide their national insurance number and date of birth which will be verified before names are entered on to the register. Moreover, registration will be effectively voluntary, a matter of ‘choice’, according to the White Paper. Citizens will be able to tick an ‘opt-out’ box to indicate that they don’t want to be on the register. These changes will be introduced in time for the 2015 general election, although the government has promised to carry over anyone who drops off the register in 2014 forWestminsterelections. It will therefore be the Scottish and Welsh government elections in 2016 that will get the first major impact.

What effect will individual registration have?

Evidence from an ongoing study of election administration funded by the McDougall Trust and Nuffield Foundation, involving in-depth interviews with electoral administrators reveals that individual registration will have three effects:

- Firstly, we should expect there to be a decline in levels of registration. The experience of election staff is that additional bureaucracy puts citizens off registering to vote. The young will be hit hard, especially when they have relied on someone else to complete the form for them in the past. At the moment, parents, University vice-chancellors and social landlords register many citizens on their behalf. They will no longer be able to do this.

- Second, there will be data-issues for local authorities. Using personal identifiers throws up a number of data-quality problems, especially when the public make errors completing the paperwork to be registered (entering incorrect national insurance numbers and dates of birth).

- Third, (and much less publically discussed) there will be enormous resource implications for local authorities. Electoral administrators have stressed that individual rather than household registration will be a much more resource intensive process. Some expect that they may have to double staff to deal with the new system. Stationary costs will increase, canvasser costs will increase and processing time will increase. At a time when local government funding is being reduced, administrators expect that they will have no time or money for ‘extras’ anymore, like public awareness or civic engagement activity. Individual registration may therefore have unintended consequences.

What effect will voluntary registration have?

The main debate about the proposals, however, has focussed on the impact of the ‘opt-out’. There are few guides about what impact this might have on levels of registration. It has been criticised by some Labour MPs as undermining the ‘civic duty’ to participate in politics. Nick Clegg has suggested that he is minded to drop it from the proposals. Evidence submitted to the Select Committee on Political and Constitutional Reform suggested that the effect on levels of registration could be dramatic. The Electoral Commission suggested that registration levels could fall to around 65%. This calculation was based on the idea that levels of registration will fall to the same levels as voting at the 2010 general election. However, (that the author is aware of) there are no more sophisticated analysis of the change. We can learn a little from overseas, however.

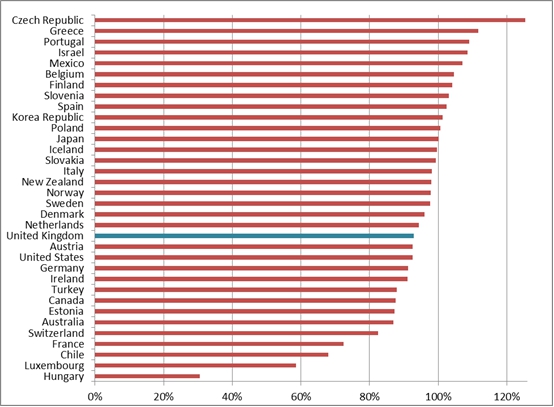

The government claims that the UKdoes not have a problem with registration levels. In the White Paper it suggests that it is ‘comparable to other similar developed countries’ and it provides a table of 5 other countries to support this point. Figure 1 shows the electoral registration levels at the last legislative election for all 34 OECD countries. The Czech Republic comes in first with a bizarre registration rate of 125% (it is common for registration rates to exceed the population rates because population rates are often estimates and registers can be inaccurate!). The UK ranks in 21st place, a good 5 percentage points behind some Scandinavian countries. It therefore isn’t ‘bottom of the league’, but nor is it challenging for a Champions League place either.

Figure 1: Registration Rates in OECD countries, at their last parliamentary election.

Note: The registration rates provided are for the latest legislative election in each country. Registration rates are calculated by the author by dividing the total numbered of registered citizens by the total voting population age. This data was extracted from the IDEA Voter Turnout Database, on 24th November 2011.

Perhaps what is more worrying, however, is that levels of registration are in decline in the UK. This was about 95% of the voting age population in the 1950s and 1960s. Estimates based on Census records suggest that the completeness of the registers was at 93.5% in 1980, 91.3% in 1990 and 91.2% in 2000. It might not be a relegation struggle yet, but there are good reasons to be concerned about what the Electoral Reform Society has termed the ‘Missing Millions’ rather than making registration levels higher.

How do countries with voluntary registration procedures compare to those with compulsory? Of the OECD states, of which the UKis one, 6 countries have voluntary registration. According to International IDEA, these areIreland,Turkey,Iceland,Canada,Chile and theUnited States. The remaining 28 have compulsory.

These six states are not all at the bottom of the league, but they are generally in the bottom half. Nowhere quite compares to Luxembourg or Hungary, butChile,IrelandandCanadaare all relatively low. Registration levels amongst these six have a mean average of 88% compared 95% to those in which it is compulsory. This is a 7 percentage point gap.

Some of the headlining grabbing claims from the Electoral Commission might therefore overstate the expected decline in registration levels that an opt-out might bring. However, it seems almost certain to have a considerable effect. When we consider that individual registration will also cause a further decline, the net effect could be dramatic. Not all those who register, subsequently vote. But contests in plurality electoral systems are often won by small margins so this could be decisive for who wins power in future elections.

We need more data on international electoral laws to learn more and take this analysis further (new research on the UK’s registration levels is expected to published by the Electoral Commission by the end of 2011). Levels of registration rates are multi-causal and these data only provides a very crude form of analysis. However, the past decade has seen considerable concerns expressed about dwindling electoral turnout, civic engagement and scepticism about in British politics. Policy makers would be wise to introduce measures to increase registration levels rather than decrease it. Lessons can also be learnt from overseas about how to achieve this. In the U.S., citizens can register to vote when accessing other government services such as their drivers licence. Such innovations are needed in theUKas well.

Toby James recently gave evidence on this topic to the Select Committee on Political and Constitutional Affairs . For a ‘menu’ of reforms that can be introduced to increase voter registration and participation, see Toby James’ article in Representation (which is free to download).

Please read our comments policy before posting

________________________________________

Toby S. James – Swansea University

Toby S. James – Swansea University

Dr Toby S. James is Lecturer at the Collegeof Artsand Humanities, at the Universityof Swansea. His research focuses on: (i) election laws and practices (particularly election administration); (ii) statecraft theory and political leadership; and, (iii) theories of policy change. He has written commissioned policy reports for national and international organisations. His research has been externally funded by the AHRC, ESRC, Nuffield Foundation and the McDougall Trust.

STOP PRESS: The UK Electoral Commission has just published a new report on the current levels of registration: http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/145366/Great-Britains-electoral-registers-2011.pdf

This suggests that UK registration levels are as low as 82.3%. Based on this and the above data from International IDEA, this would place the UK 30th/34 OECD countries.