The Conservative and Liberal Democrat government has already overturned decades of the conventional wisdom about UK governance, suggesting instead that coalitions will work stably in Britain, as they do in much of Europe. Françoise Boucek wonders if coalition governance in Britain’s current party system may even lead to future election pacts on the French model?

The Conservative and Liberal Democrat government has already overturned decades of the conventional wisdom about UK governance, suggesting instead that coalitions will work stably in Britain, as they do in much of Europe. Françoise Boucek wonders if coalition governance in Britain’s current party system may even lead to future election pacts on the French model?

In June, Prime Minister David Cameron told his MPs that the new Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government represented a ‘clean break from the past and a new start for our country’. But while it is novel in Britain, in Europe, coalitions have been the norm for decades. Currently across the 27 countries of the European Union, 20 (or nearly two thirds) are currently coalition governments.

Looking in more detail, ten EU countries (including France, Germany and the UK) have governing coalitions are composed of a mainstream centre-right party in coalition with a Liberal party. Two other countries have coalitions governments including only rightist parties (Italy and Poland) and three centre-left coalition governments are struggling with major crises of public spending (Spain, Portugal and Cyprus), all in the south. Four other countries have ‘grand coalitions’ made up of centre-right and centre-left parties. Three countries have a single party of the right in power (as in Hungary, Bulgaria, and Malta), and one of the left (Greece, also in the south and struggling with austerity pressures).

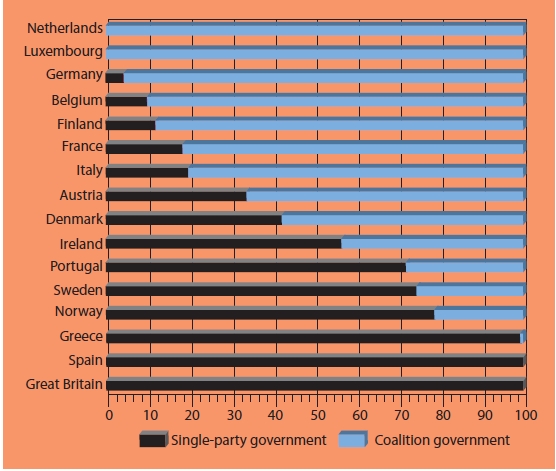

As as my chart below shows from 1945 to 1999 and based on the proportion of time in office, only three countries in western Europe (Britain, Spain and Greece) had no significant experience of coalition government.

Percentage of time of single-party governments vs. governments that were coalitions in western European countries, 1945–99

Source: Müller and Strøm, 2000

Coalition government and decision-making

Forming a coalition government was quite a U-turn for Cameron, who had castigated hung parliaments and coalitions as unworkable during the election campaign. Yet British public opinion has been generally supportive of the new coalition, at least in the short term, helped by the swift and efficient manner in which Cameron and Clegg agreed on a programme for government. The two leaders drew on the most coherent and less divisive aspects of each party manifesto. They agreed to some sensible trade-offs on education, civil liberties, constitutional reform and fiscal policy, and they generally allocated cabinet portfolios on merit rather than partisanship. Amazingly, this did not provoke any apparent discontent among the Conservative shadow cabinet members, who had to forgo their prospective slots to allow the Liberal Democrats five cabinet posts and several junior ministers.

Coalitions are often accused of being incapable of making tough decisions, unable to implement the radical policies necessary to kick-start recovery in times of economic crisis. Critics on the right often argue that, under any form of power-sharing agreement, Margaret Thatcher, for example, would have never been able to implement her neo-liberal agenda of privatisation and union restraint. Yet history shows that Thatcher faced deep divisions within her own cabinet, party caucus and British business when, in the midst of a recession, Chancellor Geoffrey Howe introduced a controversial and highly deflationary budget, described by his successor Nigel Lawson as the ‘political equivalent of the Battle of Britain’. Coalition-building pressures inside the Conservative party and the country presented as much, if not more, of a challenge for Thatcher than they did for Cameron since today both Conservative and Lib Dem have everything to gain by keeping the government coalition going.

Critics often cite Belgium as a case in point for why coalition government cannot work in the UK, but, on closer inspection, it soon becomes clear that the Belgian experience bears little resemblance to Britain’s new Con–Lib coalition. In Belgium, parties are first divided along ideological lines and then further divided along regional/linguistic lines; furthermore, the Belgian Parliament is less than a quarter of the size of the British House of Commons but 13 different parties are represented in it. Obviously, coalition building in such an environment is a complex, unstable process and the resulting government is often extremely vulnerable to the whims of its varied participants. Belgium may or may not dissolve into two separate countries but the example highlights how different the structure of the British party system is from its Belgian counterpart.

The British party system is only moderately fragmented due to a relatively homogeneous society and an electoral system that has a strong reductive effect on the number of parties. The first past the post electoral system (more accurately labeled ‘plurality rule’ in single-member districts) is strongly biased in favour of the two dominant parties.

Looking at more systematic data, do these show that there is any advantage of coalition over majority single-party government? The Dutch political scientist Arend Lijphart has examined the performance of 36 modern democracies in recent decades by contrasting the Westminster model of majoritarian democracy with the continental model of consensus democracy (characterised by power-sharing arrangements generated by proportional electoral systems). Lijphart concluded that consensus democracies were as good as majoritarian democracies in stimulating economic growth, controlling inflation and unemployment and limiting budget deficits, although coalitions tended to spend more than single-party governments. However, consensus democracies outperformed majoritarian systems on measures of political equality, women’s representation, voter turnout and greater proximity between voters’ preferences and government policies.

Where next for the UK’s coalition?

Paradoxically, coalition government offers advantages to Cameron and Clegg in dealing with potential rebels on their parties’ fringes. John Major’s government was wrecked by disunity and factional fighting over Europe. His administration began life with a majority of only 21 seats and this had dwindled to zero by the end of the Parliament, forcing Major to play complex games with back-bench rebels in order to to keep his government from collapsing.

By contrast, the Cameron–Clegg coalition has a majority of 37 seats, largely neutralising the blackmail potential of dissenting MPs on either the Conservative or Liberal Democrat back-benches. Moreover, several bills contained in the Queen’s Speech serve to pre-empt intra-party rebellions, notably by right-wing Conservatives. For instance, the European Communities (Amendment) Referendum Lock Bill promises to give Parliament and the British people a say on any proposed transfer of powers to the EU, and new government legislation promises to limit the number of non-EU economic migrants entering Britain.

Despite the government’s claim that Britain faces a fiscal hole after years of economic mismanagement by Labour, and the consequent decision to opt for severe spending cuts, it looks like the Con–Lib coalition government may survive for at least the medium term. Ministers of both parties have stressed the severity of the economic crisis and see a need to deal with it quickly.

That said, the reality of the hard grind is just beginning. The spending review due this autumn will likely call for yet more spending cuts than those announced in the emergency Budget and will severely test the coalition’s ability to survive and build consensus. Former Canadian minister of finance Paul Martin indicated recently that it is absolutely vital for deficit-cutting governments to maximise public consent if a multitude of public spending programmes have to be cut. But countrywide public consultation takes time, a luxury that Britain’s coalition government does not possess. And when Martin spearheaded such cuts in the 1990s, Canada was enjoying strong economic growth, not the recession from which the UK is desperately trying to crawl out.

If the coalition government seems to be working and if the electoral system has not been changed to the Alternative Vote in time for the next election in 2015, it is entirely possible that new patterns of party competition will emerge, energized by the experience of what a modern coalition government looks like and works like, especially if Labour is otherwise strongly resurgent.

For instance, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats might decide to co-ordinate their electoral strategies, suggesting electoral pacts between the two in certain Labour-held constituencies where the third-placed party withdraws in favour of the coalition partner’s candidate. That candidate effectively then fights the seat on behalf of the entire coalition, as in run-off legislative elections in France. Now, that really would be a clean break from the past!

Click here to leave a comment on this article.

A longer version of this article originally appeared in the magazine, PoliticalInsight; September 2010 issue, pgs 48-51.

4 Comments