There is a renewed debate for devolving power to English regions and instituting elected regional assemblies. While there are certainly undeniable justifications for doing so, public support spells doom for any new referenda on the matter. Paul Benneworth maintains that pro-devolution campaigners need to think outside the box and find ways to stimulate political mobilisation if they are to be successful.

There is a renewed debate for devolving power to English regions and instituting elected regional assemblies. While there are certainly undeniable justifications for doing so, public support spells doom for any new referenda on the matter. Paul Benneworth maintains that pro-devolution campaigners need to think outside the box and find ways to stimulate political mobilisation if they are to be successful.

English regions are making a reappearance on the national political agenda. But campaigners for a more thoughtful regional policy are falling back into their comfort zone, arguing that elected assemblies are the solution to these regional problems. Regional campaigners need first to find an innovative solution to create a regional political class that can square new authorities with Northerners’ deep-seated aversion for sub-national regional governance.

Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland were all granted directly elected authorities under the last Labour government, reflecting the relative disadvantage of these three nations to England. But it is a seductive mistake to think that comparable bodies make sense for the English regions.

The North-South Divide

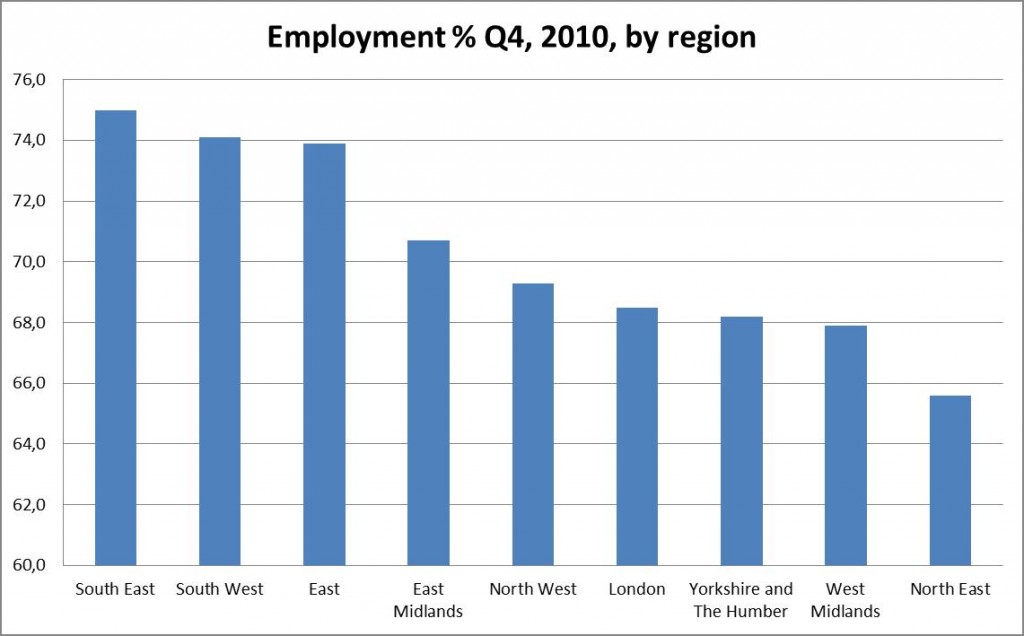

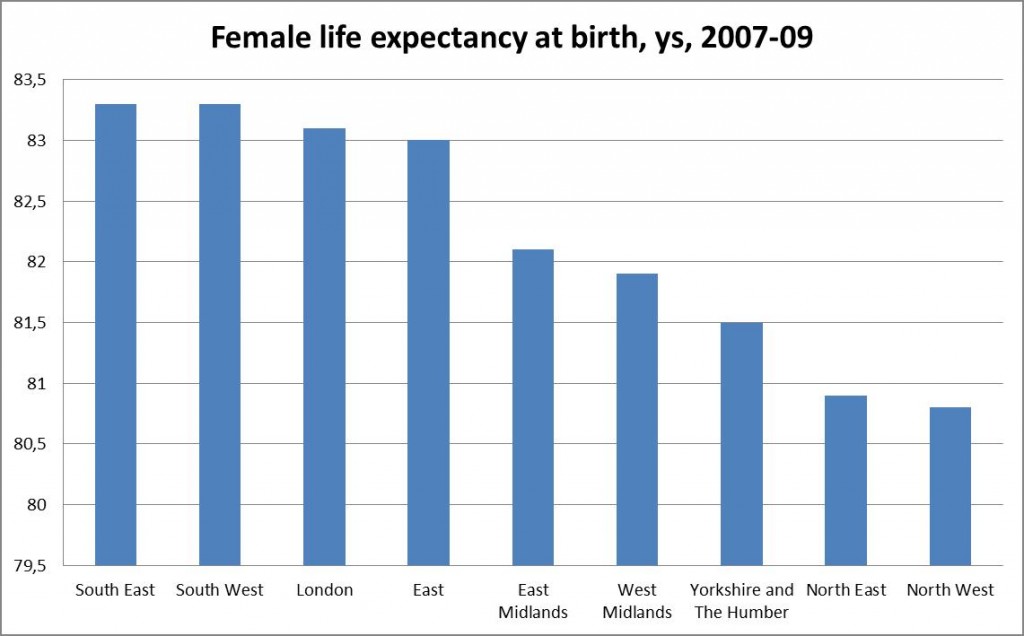

There is an undeniable regional problem in England. Northern and western regions are visibly trailing London and the south east in key indicators of social and economic development, as the charts below show.

Source: Office for National Statistics

Source: Office for National Statistics

The underlying cause of this divide is the geography of the UK’s recent economic transition in which manufacturing has declined and been replaced by new service industries. Manufacturing dominated the northern and western regions while the most profitable services emerged in the wider London city-region.

London did not notice the loss of its manufacturing as dynamic new service industries emerged. But England’s outlying regions suffered from the failure to replace those lost jobs. This started a cycle of weakness, where jobs and investment gravitated to London attracted by its strength, at the same time weakening provincial towns and cities.

A further problem is that this uneven geography means a national policy affects different parts of the country in very uneven ways. Recent government policy has followed the principle of rewarding strength rather than compensating for weakness, locking-in and even reinforcing these differences.

This is where the idea of elected assemblies for the English regions comes in – to create bodies able to understand regions’ real needs, able to tailor policy to specific problems, and ultimately, to unlock all regions’ development potential.

English Regional Assemblies or Apathy?

This idea is not recent, but dates back at least a century and a half. Churchill’s papers remind us that prime minister William Gladstone, as early as 1866, contemplated English regional devolution as part of a solution to the Irish Home Rule crisis. But, as the Empire evolved into the Commonwealth, various constitutional changes took place without fundamentally altering the position of England as a coherent political entity.

The link between assemblies and regional development re-emerged in the face of escalating unemployment in manufacturing regions during the 1981 recession. A Parliamentary Spokesman’s Working Group published proposals for newly elected regional authorities. One of the Working Group members was John Prescott who, as deputy prime minister, was later to have the opportunity to implement the proposals.

In 2002, Prescott published the Devolution White Paper; Your Region, Your Choice. In November 2004, a referendum was held in the north east on the proposal for an elected assembly with powers over regional planning and economic development. The problem for campaigners was their half-heartedness.

Political wrangling within Whitehall had greatly restricted assemblies’ proposed powers. The only sensible rationale for these proposals was technical; filling a democratic deficit. This denied campaigners a big idea as the basis for a positive campaign, and made it easy for opponents to play on public cynicism about politicians and their grandiose, money-wasting projects.

The proposal was rejected by 78 per cent of those voting with a turnout of 47.8 per cent. There was clearly no interest or desire in the region for a new tier of government as a solution to these longstanding economic problems. Shortly afterwards, Prescott shelved plans for referenda in the North West and Yorkshire & the Humber, and subsequently any further regionalisation of government activity.

The last eight years have not seen a resurgence in popular desire for elected assemblies. Recent IPPR research reported that since 2004, polling has shown a slumping of public support for assemblies, reaching a low of 10 per cent in 2011.

Real democratic renewal

With Wales having been granted another tranche of new powers, and the prospect looming of a referendum on Scottish independence in 2014, the time is certainly ripe for re-opening the English political settlement. The persistence of the north-south divide adds further impetus to the need for new institutions to address these issues.

A group of northern MPs have just launched the Hannah Mitchell Foundation to campaign for elected regional government in the north. This foundation was founded on the basis that the distinctiveness of the north necessitates political arrangements that are able to reflect and accommodate the difference. It plans to study options for devolution to the north and influence political debate in campaigning for new regional bodies.

But more of the same clearly will not be attractive to the general public, whose support is vital if the technical questions around England’s democratic deficit and policy myopia are to be addressed. The Scottish and Welsh parliaments did not just emerge because of a sense of common national identity or economic gaps with the rest of the UK. The additional element was a living political community, formed around:

- the Welsh and Scottish Offices in Whitehall,

- nationalist parties seeking votes only within those nations, and

- a strong set of civil society organisations identifying with the national political space.

None of these additional elements are present in the case of England. The vital next step for any campaign for English assemblies is to explain how this political mobilisation will take place. History has little to teach us about how this happens in different places. Perhaps the next generation of regional campaigners will be able to fill this gap and mark the start of a new phase in English regional politics.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Paul Benneworth is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Higher Education Policy Studies at the University of Twente, the Netherlands, and co-author of the Routledge book The rise of the English Regions?

A substantial problem is that the “regions” as laid out in the 1960’s which related to 1940’s war time needs in military terms are nowhere applicable in the context of England as it is now and developing. It will take some serious thinking to lay out a regional context as it might be and might work.