Next spring UK voters will get the chance to introduce the Alternative Vote system for Westminster elections. A commonly repeated claim is that the system would do away with the tactical voting that many voters resort to under the current First Past the Post system. Yet Roger Mortimore demonstrates that this received wisdom is not true. Instead new forms of tactical voting could open up under AV.

Next spring UK voters will get the chance to introduce the Alternative Vote system for Westminster elections. A commonly repeated claim is that the system would do away with the tactical voting that many voters resort to under the current First Past the Post system. Yet Roger Mortimore demonstrates that this received wisdom is not true. Instead new forms of tactical voting could open up under AV.

Describing the referendum choice that the coalition government will offer UK voters in May 2011, LSE’s Simple Guide to Voting Systems says that:

The key difference in the AV system from FPTP is that in each local contest voters fill in a ballot paper where they number the candidates in order of preference – that is, they put 1 for their first preference; 2 for their second choice; 3 for the party they like 3rd, and so on.

We count all the first (top) preferences that voters have given, as now. If any candidate gets majority support (i.e. 50% +1), they immediately win the seat. If not, the candidate who has the fewest 1st preference votes is knocked out of the contest, and we look at the second preferences of their voters, redistributing these votes to the remaining candidates in line with these voters’ number 2 choice. This process of knocking out the least popular candidate and redistributing their voters’ choices as voters intended continues until one candidate gets 50 per cent.

Many pro-AV commentators have argued that because all of a voter’s preferences are recorded under the Australian version of AV, this accordingly eliminates any need for any voter to do tactical voting. They can instead just vote sincerely 1, 2, 3, 4 etc for the candidate they prefer, confident that whoever stays in the race to win a local majority, the system will ensure that one of their preferences counts.

This claim is simply untrue. In fact there is a complex mathematical proof, the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem, mentioned also in a recent blog on AV by Raffa Hortala-Vallve. It says that no meaningful electoral system can eliminate the possibility of tactical voting. This claim is very easy to demonstrate in the case of AV.

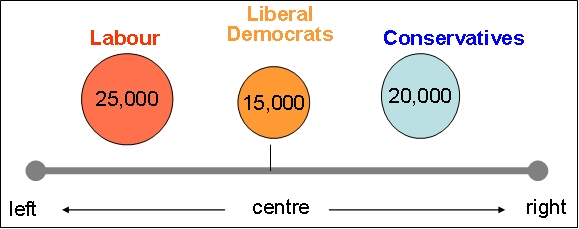

Consider the simple case of a constituency of 60,000 voters of whom 25,000 support Labour, 20,000 support the Tories and 15,000 support the Liberal Democrats. Let us assume that these people are distributed on left-right ideology scale with Labour voters on the centre-left, the Liberal Democrats grouped around the centre and the Conservative voters on the right as shown below:

Under first past the post this would be a Labour seat. But under AV whichever candidate comes third will be eliminated and their voters’ second preferences will be redistributed between the remaining two to see who wins. Given the set-up above, then Labour and Tory second preferences will split overwhelmingly in favour of the Liberal Democrats rather than to each other. But Liberal Democrat second preferences will split pretty evenly between the other two parties – let’s say 7,000 to Labour and 8,000 to the Tories.

So put yourself in the position of a Conservative voter whose main consideration is to stop the Labour candidate winning. If the Conservative candidate finishes second and qualifies for the final count, then the Liberal Democrat voters’ second preferences will split as above, boosting the final votes for the other two candidates but otherwise not affecting the final result. Labour will still win:

OUTCOME 1: No tactical voting

| First round votes | Transfers of votes | Final votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | 20,000 | +8,000 | 28,000 |

| Liberal Democrat | 15,000 | eliminated | |

| Labour | 25,000 | +7,000 | 32,000 |

But now, what if some Conservatives were so determined to prevent a Labour win that they are prepared to vote tactically for the Liberal Democrat candidate, giving her their first preferences? If enough of them did so to just push the Liberal Democrat ahead of the Conservative and into the final round, then the Liberal Democrat beats the Labour candidate with the help of all the other Conservatives’ second preferences. In the table below, 3,000 tactical votes moved from Conservative to Liberal Democrat are enough to ensure that Labour loses:

OUTCOME 2: Some Tories vote tactically

| First round votes | Transfers of votes | Final votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | 17,000 | eliminated | |

| Liberal Democrat | 18,000 | +15,000 | 33,000 |

| Labour | 25,000 | +2,000 | 27,000 |

So under AV there is a real incentive for tactical voting, because the order in which candidates are eliminated affects the result. And situations like this are unlikely to be especially rare under British conditions.

Yet if this gambit was ever applied then there is a further aspect to the possibilities for tactical voting under AV. Suppose that in this situation 1,500 Labour voters realize that Outcome 2 above will come about, and they are determined to prevent a Lib Dem win. Their best solution (perversely enough) is to switch their vote to the Conservatives. Now look what happens below!

Outcome 3: Some Tories and some Labour supporters both vote tactically

| First round votes | Transfers of votes | Final votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | 18,500 | +11,000 | 29,500 |

| Liberal Democrat | 18,000 | eliminated | |

| Labour | 23,500 | +7,000 | 30,500 |

Note: I have not got my maths wrong here: the Lib Dem second preferences split more to the Tory this time, because in Outcome 2 above 3,000 of the LibDem first round total are the concealed Tory tactical voters, and of course they will all cast their second preference for the Tory..

The Labour switchers are now just enough to push the Tory back ahead of the Liberal Democrat candidate, who is knocked out. Once again in a straight fight between the two old parties, Labour once again wins the final count (albeit with a much narrower margin than before).

So in this situation Labour supporters might need to vote tactically for the Conservative, so as to ensure that Labour wins! Of course that situation would be harder to engineer in practice – because too many Labour tactical votes would have precisely the opposite effect and give the seat to the Tories. But it is, nevertheless, real.

So in certain circumstances voting sincerely under AV can actually be counter-productive for voters, and voting tactically (i.e. not for your real first preference party) can make a lot of sense. This is a weakness of the AV system that its opponents have made surprisingly little noise about. But to repeat, tactical voting is possible in some form or another in all voting systems.

Here’s a math PhD explaining this visually and far more succinctly.

So in your example, 3,000 Conservatives vote Lib Dem so that their party don’t win, but at least Labour don’t win either?

Yeah right.

For that outcome to really work, Conservatvie voters would have to be overly-bitter fools AND be psychic.

I don’t think this works in practice simply because it is based on the premise that a large number of ordinary voters can figure this out. It’s certainly not a big deal down here in Australia.

Your examples are severely flawed.

You have judged tactical voting using a three party system. Nearly ever constituency has more than three candidates. Therefore the person(s) eliminated first are not going to be one of the three.

I realise that the majority of votes are likely to go to the three, but where UKIP, Greens, strong Independents etc are involved, the outcome will not be as simplistic as your argument and I would hazard to guess that the average voter in the street would not bother to work out permutations.

Worth reading this response: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/?p=3915

To respond to Patrick Dunleavy’s point.

Fair point. Perhaps a touch utopian.

Multiple candidates from each party may not happen in the first few elections. It may not ever happen. The threat of it, however, I think will be a potent way of moving power from central offices to local activists and from local activists to the general electorate.

AV lowers the barriers to entry for new parties or split ticket candidates because it reduces the risk of splitting the vote for both party and voter.

It works the same way as Microsoft’s monopoloy. The fact that it is comparatively easy for new entrants to create a better product keeps Microsoft’s quality and price at a level closer to that expected in a fully competitive market with many actors. The same, I think, with AV. The fact that with AV if I don’t like my party’s candidate in an election I can run myself without fatally damaging my party or my philosophy’s chances of winning should keep parties and politicians honest.

Perhaps I could respond to Mark Wilson’s comment and say that on this blog LSE has already assembled quite a lot of high quality information that we hope will be useful for citizens considering the AV reform, including the following recent blogs, taking different points of view:

• Tactical voting can still occur under the Alternative Vote, and it may lead to unexpected outcomes

• Every key ‘Westminster model’ country now has a hung Parliament, following Australia’s ‘dead heat’ election

• How much of a change would the Alternative Vote really be? Why all MPs should support reforming the electoral system. It is a key step in restoring their own legitimacy with the public

• Is Alternative Vote a better voting system? It depends…

• The AV referendum could still let voters choose between Australian AV and the London form of AV

• Where to now for the UK? Some lessons from New Zealand

• Why the Cameron-Clegg coalition will be a shock to both Tory and Liberal Democrat voters

• The LSE’s simple guide to voting systems

• Constitutional reform – what the three parties are promising

• How unfair or disproportionate is the UK’s voting system for general elections?

For Dan Sutton’s interesting point, can I add a dampening thought which explains why his utopian vision will not happen. Under the type of Alternative Vote being proposed, voters only fill in as many or as few preferences as they choose. In UK conditions, a good proportion of voters will only fill in one or two choices, and probably only around a third or less will fill in more than four or five choices. So no party will risk splitting their vote across multiple candidates for fear that their voters will not fill out a complete slate of their choices and thus that the total party vote will be less than if they put up only one candidate.

The only way around that is to do what Australia used to do (but has long since abandoned), which is to require all voters to number all the candidates in a sequence – and to reject ballot papers that do not cover all the candidates. This is objectionable because it may force people to express preferences they do not have.

So, nice idea Dan, but it will never happen so long as parties can prevent it. However, if there are local party splits (e.g. a dissident candidate from one party with a local following stands against the official candidate), then AV might act to limit the damage more than in FPTP. Both Labour and the Conservatives are worried by this though – fearing that AV may encourage more splits than FPTP.

For me one of the most attractive features of AV is the ability to have implied primaries.

At the moment the debate is focused on the situation that might arise if each party only put up one candidate.

However, there is no reason why a party should not field two or more candidates in the same seat.

That would allow me as a voter to pick which party I preferred and then pick which of their candidates or wings I preferred. I could also choose between supporting a candidate who was a good constituency MP, or one who contributed to national debate or one who firmly voted with the whips as my notion of a good MP struck me.

I could also influence which of the candidates from parties that I don’t get want to hold the seat did well. A left wing Tory might be more likely to get my vote than someone to the far, far left of the Labour Party. The Conservative and Labour Parties could see from the rankings which of their candidates attracted votes.

It would mitigate the situation where local branches are heavily influenced by Central Office or by radicalised factions. There would be nothing to stop a Europhile Conservative standing if she felt that her constituency party had been taken over by a cabal of Euroskeptics, for example. MP’s who did a good job for their constituents could defy the whips knowing that even if they were deselected as an official candidate they could stand on a quasi-party basis and still hope to be returned. Corrupt MP’s could be punished by voters without necessarily hurting the party that they support.

The choice of MP shifts more towards the electorate and away from Party HQ or Local Constituency Offices.

AV with multiple candidates from various parties would allow me as a voter to vote for the person, policies and principles of my choice.

Glad to see that the LSE has joined the debate on Electoral Reform. Given the organisation’s rich past for political debate it would disappointing not to see the LSE’s viewpoint on this subject. So I was disappointed to see an article such as this. Regrettably this is a ‘dancing on a pin head’ article in terms of the importance of the much wider debate on Electoral Reform. Indeed I would expect the LSE to be at the forefront of the debate on AV and perhaps the bigger questions surrounding PR.

For those of us who advocate for at very least a ‘proper’ debate on the merits PR and i have only been doing this since 1981, and I am now 47 years old,this is a debate who’s time has come. Yes AV is not a perfect answer to the faults of First Past the Post (FPTP), indeed many of us involved in the PR debate would want alternatives debated but those options are not on the table at present. But to simply trash the idea of AV on the merits of Coalition is very short sighted. Lets kill this debate once and for all. In any electoral system there will be good coalitions and bad coalitions. The acid test is if you have a bad Coalition can you the people vote it out?

With the proposed change to our voting system we should see this more of another of Britain’s pivotal moments in its history, and specifically on the history of voting. We may have finally achieved universal franchise but did we also overcome the issue of whether we also have a fair voting system. This has been as equally important issue as achieving universal franchise. Regrettably the ideologically pure Left, and Right would say YES, the rest of us have now said NO! The debate now begins!!

As a voter, I would find it very confusing if a canvasser for the party I intend to vote for told me to vote for another party’s candidate instead. Also just because I support that party, it does not follow that I would be willing to vote exactly as the party managers tell me to.

I disagree with some people’s assessment that “it’s so confusing, so everyone will just vote honestly.”

No, what they’ll actually tend to do is vote for what they consider the least-risky choice; whichever of the two leading parties they like most (or, if you prefer, dislike least).Which, by the way, is exactly the same tactical decision that voters are encouraged to make under FPTP: to pick the “lesser of two evils”, driven mostly out of fear. Humans are, by nature, risk-averse.

The actually change from using AV rather than FPTP would be very minimal because of precisely this similarity; the biggest difference would be the increased cost for counting the ballots.

As an aside, the “too hard to coordinate, so it doesn’t matter” I think has an equilibrium (in the 3-candidate case) when half of all voters are voting tactically. So the proper coordination may be to instruct everyone to flip a coin in the voting both; heads, vote honestly, tails, vote tactically.

As a further aside, there ARE, in fact, voting methods which have no such bizarre tactical strategies *in 3-candidate contest* (in other words, methods which beat the Gibbard-Saiterwaite theorem for 3-candidate elections): approval voting (vote for as many or as few candidates as you want; most votes wins) and score voting (give each candidate a score from anywhere in a given range; highest score wins).

Under these methods, it is always–honestly or tactically–best to give your favorite an approval/the top score, and your least-favorite no approval/the bottom score. There is some consideration to be given on what to do with your middle-favorite, but the fear-full consideration is that you’ll get your second-choice instead of your first, while under all other voting methods, it is that you’ll get your last instead of your first; so it’s a clear improvement.

You say something which is contradictory here —>”So under AV there is a real incentive for tactical voting, because the order in which candidates are eliminated affects the result. And situations like this are unlikely to be especially rare under British conditions”. – ahh. just before this sentence you have shown Conservatives voting tactually and they lost – can you please explain what incentive there is to vote tactically then. You have presented information and then put a statement which is totally contradictory to the facts to ‘prove’ your point !!!!!! So as people have already said under PRP tactical voting can work – under AV it can produce even worse results for those tactically voting. There is no incentive to do it under AV whereas there is a real incentive under FPTP

Its a nice contrived bit of number work but it is completed meaningless. – What would be more useful is to work out statistically how unfair FPTP is compared with AV. – ahh, this is already presented on the ERS website which shows that AV is fairer and more democratic.

So to sum up having considered both the article and the comments:

Tactical voting is technically feasible under AV in some cases, but difficult to reliably accomplish and therefore fairly unlikely to actually happen in a parliamentary election.

Spot on Dan! In short: you can vote tactically if you insist, but it is more in your interests to vote sincerely.

With first past the post, the opposite is usually the case.

In the scenario given I think the Conservatives have only to persuade 2,250 Lib Dem voters to cast their second preference for the Consertatives instead of Labour for the Conservatives to win the seat. I don’t know how easy this would be compared to persuading 3,000 Conservative voters to vote Lib Dem in order to make sure that Labour doesn’t win.

It’s a bit of an even prize. If you put effort into shift Conservative voters to LD you get a LD seat not a Labour one, with no guarantee that the LD you’ve helped elect will support a Con Dem coalition. If you put effort into persuading LD voters to vote for you get a seat.

The scenario also ignores the situation where there are more than three parties. Flanking parties on either side of Labour (Socialist Workers or Respect) and the Conservatives (UKIP) would make for interesting tactics. As does the addition on non-linear spectrum parties like the Greens or the Nationalists or extremisst like the BNP.

The tactical position for voters is so murky that the only credible position is to vote sincerely. The tactical position for parties is also so murky that any attempt to manage a tactical voting campaign is going to be very difficult, with many chances to misread the situation and get it wrong and only a narrow chance of getting it right. Getting it wrong crucially would be career suicide for party manager who tried and failed.

You could have a tactical campaign but it’s so risky for voters, parties and party managers that I don’t see it ever happening.

So to come back to your examples, Roger, let’s have a think about campaign strategy in a constituency of this type.

You have constructed a constituency where the Labour candidate has ~25,000 supporters, the Conservative ~20,000 and the Lib Dem ~15,000.

Now, given that Lib Dem transfers split pretty evenly (or even slightly in favour of the Tory at the moment), we’d only need a Lab-Con swing of about 2,000 votes for the Tories to be in with a strong chance of taking the seat. That kind of swing is within the margin of error of most polls, and could happen in a single day.

You claim that the optimal strategy for Conservative voters would be to accept the constituency is lost, and try to shoehorn in the Lib Dem candidate.

Would any Conservative candidate in their right mind advise their supporters to vote in this fashion, when they themselves have a clear chance of winning?

Therein lies the difference between tactical voting under FPTP and so-called ‘tactical’ voting under AV. Under FPTP, it is the supporters of rank outsiders who can confidently cast a tactical vote for another party. With AV, voters are not forced to vote tactically, and the risks of voting tactically outweigh the (unlikely) rewards.

As for Tim Roll-Pickering’s laughable attempt to prove that tactical voting happens in Australia — a couple of misguided comments on websites do not amount to a campaign of tactical voting. You acknowledge yourself that boundary changes (or how about just a change in voter opinion?) were behind the Nationals taking that seat.

In Britain, we have tactical voting websites, tactical voting guides in national newspapers, huge numbers of voters (at least 15%) claiming to vote tactically, and a productive tactical strategy for voters to follow.

Vote ‘Yes’ for the Alternative Vote if you’d like the chance to vote honestly and effectively for your local MP.

Tim,

The problem with your argument is that if a tactical voting campaign isn’t ‘transparent’ it won’t work. You try explaining it on the doorstep.

How can any of that be boiled down to a message that is as simple as a bar chart or “it’s a two horse race”.

It is also quite clearly the case that this example only applies to three way marginals where tactical voting falls apart under any system (see Watford, Hampstead and Kilburn and Camborne and Redruth) because all the parties spend all their time and energy putting out conflicting messages. In the case of a two way marginal, which is to say the vast majority of non-safe seats (where tactical voting would be equally pointless), it wouldn’t work at all.

As I say, this is fascinating sums, but it has no practical real world application. The best thing you could say for it is that it might make some small impact on the handful of 3 way marginals. Given that tactical voting is the norm for all marginal constituencies under FPTP, the only thing this debate serves to do is to highly how much worse FPTP is than AV.

Roger, you’ve misrepresented my argument (nothing to do with whether the Australian version is used), so I’ll quote it in full:

“t is simply not practical to vote tactically under AV. You would need detailed knowledge of the kind only available AFTER the count.

Let’s look at the kind of constituency profile needed to vote tactically under AV. The rules are quite basic:

1. The 1st place party (Party A) can lose to the 2nd place party (Party B) on preference transfers — i.e. Party A has less than 50% first preference support.

2. The Party A can shed enough ‘tactical’ first preferences to the 3rd place party (Party C) to switch the order of elimination without losing its own place in the ranking — i.e. the difference in first preferences between Party A and Party B is greater than that between Party B and Party C.

Already we’re envisaging something pretty difficult to predict, even with accurate polling. If you could predict constituency results to this level of accuracy then you would make an absolute fortune in the betting markets.

Given that Party A, in this context, would stand a reasonable chance of winning (based on pre-election expectations), it would be insane for that party to ask its voters to switch to Party C in order to prevent Party B from winning.

This is very different from FPTP tactical voting, where it is supporters of Party C (the third-placed party) who are encouraged to vote tactically — to choose between Parties A and B.

What I’m saying is that, in the real world (where elections happen), the secrecy and unpredictability of elections means that tactical voting is not an optimal strategy under AV.”

Andy White

Electoral Reform Society

James, I don’t think you’re right – party machines are perfectly capable of doing polling in marginal seats on second preferences. They will only ever want small numbers of people to vote tactically (clearly the above examples would fail if too many voters voted tactically), so they can rely on tight networks of party members (plenty of seats where party members plus their immediate families equals well over a thousand voters) or else send carefully targeted direct mails out to solid party supporters explaining the situation.

Of course, this does mean AV will give a further advantage to parties with more money to spend who can afford more polling, targeted mail etc.

What is fair to say is that FPTP encourages more voters to vote tactically than AV, but does it in a more honest, transparent way than AV would. AV allows elites to manipulate the result more effectively.

There has been some tactical voting in the recent Australian election, mainly to get third force candidates and independents into the last two. In the seat of O’Connor the National Party has been challenging the Liberals for a long time but until now has never been able to overtake the Labor Party to reach the final two, even though the sitting Liberal MP Wilson Tucky is widely disliked on the left. A new set of boundaries complicates things but in the run-up to this election a number of Labor inclined voters stated online they would vote Nationals 1 Labor 2 despite their (main) preferences being the reverse because they wanted Tuckey out. This time the Nationals made the final two and took the seat.

There’s also tactical campaigning whereby parties can and do run a light campaign in order to allow themselves to be overtaken to achieve this effect. In some by-elections a major party (usually a sitting government in opposition vacancies) doesn’t even stand candidates and forces their rival to face a challenge on the flank.

Nice theory, but outside the ivory towers of academia, does it really have a real world application?

Under FPTP, political parties plough considerable resources into persuading voters to vote tactically. Despite this, and despite having very simple messages to push (“vote blue get red” for instance), they rarely have more than a marginal effect, even in target constituencies.

Under your theory, organisations would have to exist to be able to plough serious resources into pushing out targeting strategies that are far more complicated. In place of bar charts, you are purporting leaflets going out explaining the “Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem”.

You are right to say that no system cannot be gamed. What you can’t claim is that AV would result in more tactical voting than FPTP. It is transparently not the case that that would happen. I would suggest that the reason the ‘no’ campaign is unlikely to make a lot of noise about this is that it knows full well that under FPTP tactical voting is not a bug but a feature.

If you want to make tactical voting less of a feature of UK politics, then you will vote for AV on 5 May. Nothing you have written here changes that fact.