(Credit: Bob Jones via Wikimedia Commons)

Jules Birch decries the new legislation against squatters. Whilst squatting where someone else is living is rightly criminal, doing so in a long-empty house should not be.

Back in the early 80s I did what many people arriving in London did: I squatted in a house that had been left empty. Anyone doing the same after this past Saturday will be a criminal.

The house in question was owned by the Greater London Council (GLC) and like many others owned by local authorities all over London it had been left empty for years because of a road scheme or a slum clearance scheme that was never finished. Nobody was living there and, given the big hole in the floor of one of the bedrooms and the water streaming down the walls of most of the others, that was understandable. So when we squatted it we were not denying anybody else a home, we were simply fixing it up and creating one for ourselves in what became one more squat in a whole street of squats. Given that we were all on the dole (this was 1981, the worst time to be a graduate until now) we were probably even saving the taxpayer money.

After several months we were taken to court by the GLC but at the last minute we were helped by a local short-life housing association (the first time I had ever heard the term) that was allowed to take over the house on a proper license. Last time I looked it was still there although I had soon moved on. Ironically enough, years later I was to meet the man who signed the eviction notice on the editorial board of ROOF magazine. I also realised that I had come in at the tail-end of a wave of squatting across London that included everyone from Robert Elms to the cousin of a certain future housing minister (the 101ers, the forerunner of The Clash was even named after the squat where they lived in Walterton Road). Then, as now, there were people who suffered because of squatting but the vast majority of squatters simply wanted somewhere to live. In the process, they must have saved thousands of abandoned homes across London.

The trigger for memories of those days is obviously the imminent passing into law of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (LASPO). Government ministers have been all over the air waves proclaiming that they are ‘criminalising’ squatting. In fact, as they very well know and were told by 160 housing academics, solicitors and barristers, it was already a criminal offence to occupy a home where someone is living or is about to live. LASPO makes it criminal to enter any residential building regardless of how many years it has been empty and regardless of whether it has simply been abandoned. Crispin Blunt told the Today programme this morning that it was about ‘fairness and justice for homeowners’.

For more about the details of the Act and about its enforcement, see the excellent Nearly Legal blog. There are already doubts about how it will work, with worries that it could be used by unscrupulous landlords to evict their tenants matched by concern that clever squatters could delay things so much by making up fake tenancy agreements that the police will get sick of enforcing it and resort to the usual ‘it’s a civil matter’ cover they use in other housing cases (see @LettingFocus on Twitter for more on this).

Obviously my squatting past and the fact that I write so much about housing put me on the side of those who maintain that the really criminal thing here is keeping homes empty rather than using them as homes. It makes me sit up and take notice when Crisis points out that the new law will leave vulnerable homeless people facing up to six months imprisonment or a fine they cannot pay. It makes me think about how many people who end up working in or in some way involved in housing used to be squatters.

However, it also makes me look for something to go with such a draconian crackdown: tough new measures against property owners who leave homes empty in the middle of a housing crisis. Prodded into action by the Liberal Democrats, the coalition has at least done something with extra funding and new homes bonus for work to bring empty homes back into use and legislation to waive council tax relief on some empties. What’s needed though is a simple and enforceable way to take over the management of long-term empty properties from owners who refuse to do anything with them. Back in 1981, many empty homes were already owned by local authorities or government departments, which made things easier for a wave of short-life housing associations to get involved. However, as last year’s Great British Property Scandal showed, 88 per cent of long-term empties are now privately owned.

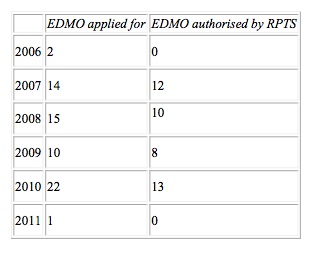

One mechanism already exists and has done since 2006: an empty dwelling management order allows a local authority to take over a long-term empty for 12 months (on an interim basis) or up to seven years (for a final order) and let it out. The trouble, as the table below from a parliamentary answer last year makes clear, is that councils have applied for less than 100 EDMOs since 2006 and less than 50 have been granted.

That’s out of 279,000 homes in England that have been empty for more than six months.

Whatever the reasons for that, whether EDMOs were too cumbersome or too expensive or both, you might have thought that the priority would be to make them easier to use while retaining protection for owners whose property is empty for good reasons. Instead the opposite happened. Exactly the same papers that have cheerled the clampdown on squatting mounted a sustained assault on EDMOs with a succession of questionable anecdotes. In 2006 the DCLG even felt moved to issue a statement denying misleading claims made in the press.

In 2011, Eric Pickles at last promised action. However, far from making EDMOs more effective in tackling the scandal of empty property, he was actually intent on making them much more difficult to use. In future, he said, EDMOs would only apply to properties that ‘have become magnets for vandalism, squatters and other forms of anti-social behaviour’ and the property would have to be empty for more than two years with owners given at least three months’ notice. For a full account of EDMOs, see this research briefing from the Commons Library.

A real solution to the scandal of long-term empty property would of course involve far more than just EDMOs. The point of interest here though is the language in which the policy was framed and the ideology behind it. In a phrase that could have been lifted straight out of Crispin Blunt’s interview or statement today on squatting, the headline on the Pickles press release was ‘Pickles acts to protect the rights of homeowners’.

Just like the clampdown on squatting, this was really about protecting property rights. Squatting somewhere someone else is living is rightly – and already – a criminal offence. However, properties that are left empty in the long term are no longer homes. They become homes when someone lives in them. That is what I was doing back in 1981 and that is what people in far more housing need who will now become criminals are doing in the middle of a housing crisis in 2012.

A version of this article was originally posted on Jules Birch’s blog: http://julesbirch.wordpress.com/

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Jules Birch is a freelance writer and journalist, mostly about housing and social affairs. He is currently studying for a doctorate in social science at Bristol.

It’s not as simple as you say. If a private owner leaves their property empty, that is their choice and does not entitle squatters to just break in, causing damage. Even with unoccupied Local Authority property, there has to be some sort of law and rules, otherwise itls just anarchy, a free for all.