Recent weeks have seen large scale student protests over the Liberal Democrats’ ‘betrayal’ over tuition fees, and Nick Clegg’s party is now seen by some as the scapegoat of the coalition. While coalition style-politics are relatively new in Britain, according to Chris Gilson, New Zealand can offer some important lessons in how coalition governments might continue – or end — in the UK.

Recent weeks have seen large scale student protests over the Liberal Democrats’ ‘betrayal’ over tuition fees, and Nick Clegg’s party is now seen by some as the scapegoat of the coalition. While coalition style-politics are relatively new in Britain, according to Chris Gilson, New Zealand can offer some important lessons in how coalition governments might continue – or end — in the UK.

It is now clear that the honeymoon period for the coalition government is over. Net approval of the government is now well into the negative, at minus 14 per cent, and Labour has had as much as a 5 per cent poll lead over the Conservatives in the past month. It’s been a rough time of late too for the Liberal Democrats, with massive student protests and Nick Clegg facing often severe criticisms over his apparent u-turn on tuition fees.

Tremors in the Liberal Democrats are not new, though. In June, barely two weeks after taking up the deputy leadership of the Liberal Democrats, Simon Hughes announced his plans to challenge the post-Budget finance bill, and since then has taken major issue with David Cameron’s plans to end lifetime tenancy for social housing, and floated the idea of a Lib Dem veto on government policy. Nick Clegg’s party is learning the hard way that a junior coalition partner must fight, and fight hard to push its agenda, or they risk becoming a mere adjunct to the Conservative party.

Such battles within government are not new in New Zealand politics, a Westminster style democracy where hung parliaments have been the norm for almost 15 years. Prior to this, under the First Past the Post (FPTP) system, Kiwis consistently experienced the kind of electoral disproportionality that is commonplace in the UK, with elections throughout the 20th century giving results favouring the two largest parties, National and Labour.

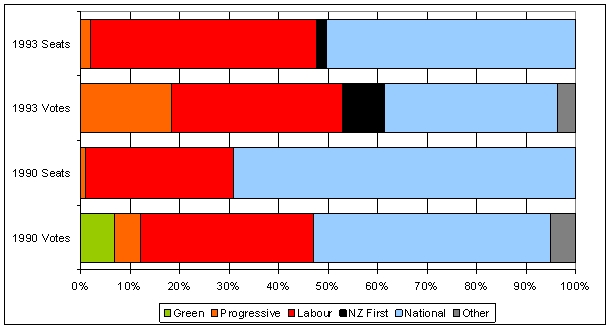

In the 1993 election, the ruling party, National, had won a narrow majority with 50 seats in the 99 member assembly with only slightly more than 35 per cent of the popular vote (Labour gained 34.7 per cent of the vote and 45 per cent of the seats). Only two smaller parties were able to break through with four seats between them. In 1990, it was even more disproportionate; National won nearly 70 per cent of the seats with only 48 per cent of the popular vote:

Seats and Vote shares in New Zealand General Elections 1990, 1993

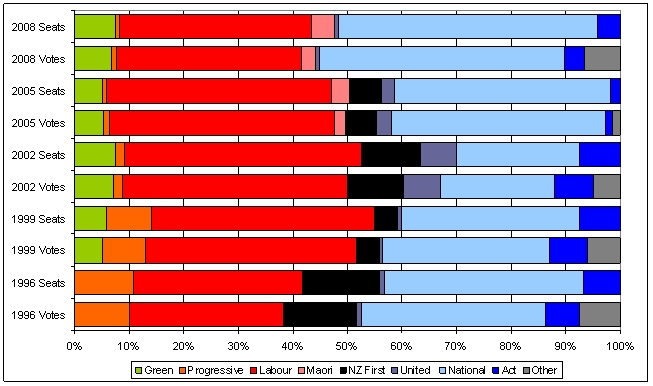

After a sustained pro-proportional representation (PR) campaign, Kiwis chose the Mixed Member Proportional system (known as the Additional Member System in the UK) in 1993 after two referendums. The first election under that system was held in 1996; looking at seats and vote shares from then to now, we can see that the New Zealand parliament has become much more representative:

Seats and Vote shares in New Zealand General Elections 1996-2008

The 1996 election took New Zealand into relatively uncharted political waters. In the enlarged 120 seat parliament, the National party had won 44 seats and the Labour/Alliance left-wing bloc, 50. The centrist New Zealand First, under Winston Peters, had won 17 seats, and he became ‘kingmaker’, as Nick Clegg was after our own election in May. At the time, most commentators expected Peters to support the Labour/Alliance bloc, and put an end to the National government which had been in place since 1990. Instead, after leaving the country waiting for a month without a government, and receiving overtures from both parties, Peters announced that New Zealand First would enter a coalition with the National Party.

While the government was initially stable, by the end of the 3-year parliamentary term there had been numerous defections from New Zealand First and the coalition had fallen apart. In the 1999 election, voters punished New Zealand First for choosing National, and the party was reduced to only 5 MPs (and 4 per cent of the vote), and thus lost the balance of power. Sensing the electorate’s dissatisfaction with the way the 1996 coalition agreement had been formed, Labour leader Helen Clark moved quickly to form an agreement with the Alliance Party, and an informal agreement was made with the Green Party, newly entered to parliament. This agreement was reached two weeks after the election in stark contrast to the 59 days that New Zealand First kept the country waiting in 1996.

In the 2002 election Labour was returned with 52 seats, but the implosion of its former coalition partner the Alliance (and its replacement with the 2-seat Progressives) meant that they had to extend their informal coalition to another party, the more centrist, United Future (the Greens were eschewed this time due to policy clashes). Finally, in 2005, Labour was returned with 50 seats and sought support from three other parties; the Progressives, now with one seat, New Zealand First and United Future, all on an informal confidence and supply basis.

In 2008 the Labour government lost power to John Key’s National Party – who formed a coalition agreement with the Maori Party, the far-right ACT party and the now one-seat United Future Party. This agreement was made within in days of National’s election result, echoing Helen Clark’s quick government formation in 1996. However, Key’s coalition has been under much strain since; with the larger party being seen by some to be playing the smaller ones off each another (John Key has earned the moniker ‘Teflon-John’ from some commentators on the New Zealand left).

In April, Maori Party co-leader Pita Sharples went on an apparently covert trip to the UN to sign to the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, much to the consternation of the government’s right-wing coalition partner, ACT. Since then ACT have recently seen the resignation of their deputy leader and an MP, and a plummet to their poll ratings which could see them kicked out of parliament in the next election. New Zealand may well face a different coalition configuration in 2011.

So what can Nick Clegg and the Liberal Democrats learn from the Kiwi example?

As experienced by smaller parties in New Zealand, coalition government can eventually lead to electoral destruction, as voters punish smaller parties for the failings of the government. David Cameron has cannily positioned Chief Secretary to the Treasury, and Liberal Democrat, Danny Alexander as the ‘face’ of the coalition’s cuts programme – his name and position have been mentioned in the news media nearly 5 times a day since he took up the post. Contrast this with Liam Byrne who held the post for Labour for nearly a year and was mentioned less than twice a day over that time.

While the Conservatives have been sitting relatively comfortably on polling results of over 40 per cent (although Labour is now often matching or beating them in the polls), the Liberal Democrats now have regular results as low as 9 per cent, a very long way from their post-debate highs before the election, and current seat predictions have them on as little as 17 seats in an election.

The result of the AV referendum next May is now looking more likely to result in defeat for the pro-AV lobby, which has lead many commentators to ponder whether or not Clegg will continue to support the coalition if it fails, especially with the government pursuing a largely Conservative agenda. However, given the Liberal Democrats’ recent poll results, Clegg may not have a choice but to continue to support the government and gain whatever meagre concessions he can.

In any case, even if AV does succeed, we will not be seeing a substantial realignment of the electoral map beyond the ‘Big 3’ parties – under some predictions given current polling, the Liberal Democrats may get as little as 32 seats under AV. Only with the adoption of a an actual PR system will we see smaller parties and groups actually represented in parliament, as is the case in New Zealand.

Unlike New Zealand, however, there is no obvious coalition partner to step up and take the Liberal Democrats’ place in government, so their place is secure in that sense. But in reality, Clegg has little power to really influence government policy on the major issues, such as Trident and welfare reform, and may well be facing electoral doom in 2015 with an electorate ready to punish him for the Conservative’s cuts. By abandoning AV and pushing for a referendum on real PR, as New Zealand did, as well as listening to party rebels, the Liberal Democrats’ may yet win back the respect of voters and ensure they are no one-term-wonder.

This article previews the McDougall Trust Workshop ‘Hung Parliaments, Coalition Governments and Proportional Representation: the New Zealand experience’ on 9 December. Please click here for further details.

Click here to respond to this post

Please read our comments policy before posting

1 Comments