This month marks 25 years since a national minimum wage was introduced in the UK. Once a controversial policy, due to fears that it would lead to fewer jobs, it has instead proven to be highly successful. The minimum wage is now a fully accepted part of the labour market. Stephen Machin reflects on how the minimum wage has reduced wage inequality and what needs to happen next.

Even in April 1999, £3.60 was not a lot of money, but it was a big deal. It was the hourly rate of the UK’s first national minimum wage (£3.00 for 18-21s), and the idea then was that it was better to start low and evaluate than run the risk of setting it too high. There was still concern expressed in many quarters that a minimum wage could lead to job losses, despite research including several studies from the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance finding no evidence that wage floors damage employment. The Low Pay Commission, which was set up to make recommendations and monitor the impact of the rate, recommended the £3.60 rate in its first report, which drew on written evidence from 500 organisations, more than 200 visits meeting businesses and workers around the country and cited more than 350 research studies.

What is now known as the national living wage (a new floor introduced in 2016) will rise to £11.44 for those aged 21 and over from 1 April 2024.

The rate did not stay low for long. The UK is now seen as a relatively high minimum wage country. By 2022 it was the eighth highest in 25 OECD countries. What is now known as the national living wage (a new floor introduced in 2016) will rise to £11.44 for those aged 21 and over from 1 April 2024.

The economic effects of minimum wages have proven to be a controversial area over the years, with much of the controversy being pinned to the questions of whether minimum wage floors negatively impact employment or not. But here I am interested in another question – how minimum wage regulations have affected wages and their distribution.

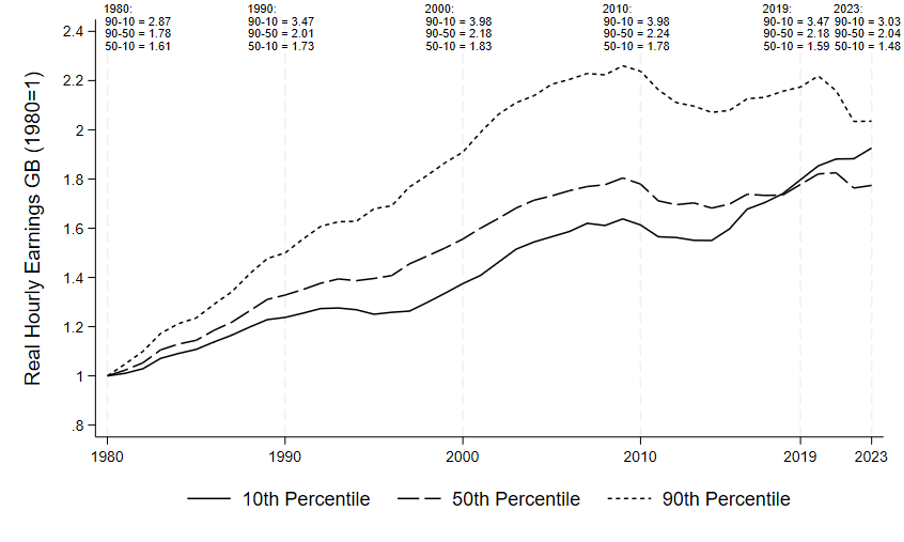

The distribution of wages has become more unequal in the UK since 1980. For much of the earlier part of the period from then until now, wages for workers higher up the distribution rose more quickly than for those lower down. More recently patterns have changed somewhat, as the peak level of hourly wage inequality was reached in the early to mid-2000s, with reductions following, but with the overall inequality level is still higher than it was in 1980.

Figure 1 shows patterns of real wage growth at three percentile points of the wage distribution from 1980 to 2023, and inequality ratios from them at the top of the chart. In 1980 the 90th percentile worker earned 2.87 times as much as the 10th percentile worker. This rose to a peak of over 4 in the early 2000s, and then has fallen back now by quite some way, down as far as 3.03 in 2023. Note that the entire 1980–1999 increase in lower tail inequality (the 50-10 ratio) was fully reversed by 2019, and by more since then. This is because of the minimum wage boosting the 10th percentile by a lot.

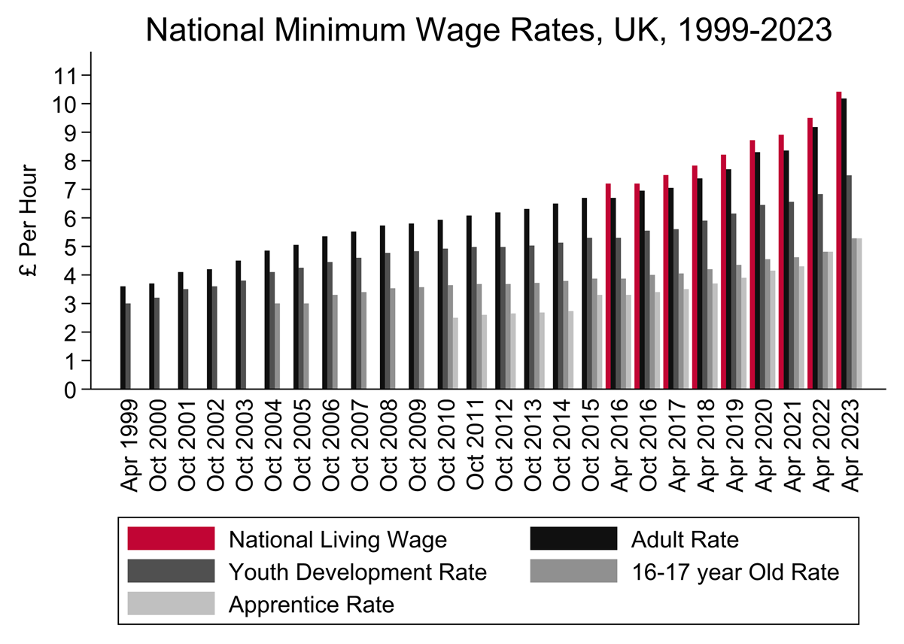

Figure 1 The evolution of the national minimum wage from its introduction in April 1999 until 2023 is shown in Figure 2. This also shows how the institutional structure of having several minimum pay rates (that vary by age and, more lately, apprentice status) has altered. The figure makes it clear that the minimum wage rose rapidly over time, and that new minimum wages that were added over time. At the time of its inception in 1999, there were just two rates, one for workers aged 22 and over, and another for younger workers aged 18 to 21. Over time a rate for 16 to 17-year-olds, and for apprentices also came in. But the most important structural change was the (at the time) unexpected introduction of the national living wage in April 2016, a substantively higher minimum for workers aged 25+ that resulted from George Osborne’s hastily announced post-election win July 2015 budget.

The evolution of the national minimum wage from its introduction in April 1999 until 2023 is shown in Figure 2. This also shows how the institutional structure of having several minimum pay rates (that vary by age and, more lately, apprentice status) has altered. The figure makes it clear that the minimum wage rose rapidly over time, and that new minimum wages that were added over time. At the time of its inception in 1999, there were just two rates, one for workers aged 22 and over, and another for younger workers aged 18 to 21. Over time a rate for 16 to 17-year-olds, and for apprentices also came in. But the most important structural change was the (at the time) unexpected introduction of the national living wage in April 2016, a substantively higher minimum for workers aged 25+ that resulted from George Osborne’s hastily announced post-election win July 2015 budget.

Figure 2

How does the minimum wage relate to the patterns of real wage growth and inequality? The answer is that it strongly relates, and that the minimum wage has strongly impacted wage inequality in the labour market, and fully reversed the previous rise in lower tail inequality that occurred before its introduction. Figure 3 hones-in on the real hourly wage growth at the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles since its introduction in 1999, and wage growth at the minimum wage level itself. The level of the minimum wage, introduced at £3.60 per hour in April 1999, rapidly climbed through the lifespan of the minimum to £9.50 by 2023, as shown at the top of the chart, along with the same three inequality ratios as in Figure 1.

Figure 3:

Figure 3 shows that real wage growth at the minimum wage was faster between 1999 and 2023 than at the three points of the wage distribution. In fact, of the four lines shown, the minimum wage line grows the most (by 60 per cent since 1999), the 10th percentile also grows (by about 40 per cent) and the 50th and 90th grow by only a small amount. In the period of real wage stagnation since the end of the 2000-2010 decade, in the wake of the global financial crisis, only the minimum and 10th percentile show growth of any note.

There are two pertinent conclusions that follow. First of all, the reason why between 1999 and 2023 the 50-10 ratio pulled back all (plus a little more) of the rise that took place from 1980 to 1999, is the minimum wage. Second, this occurred by raising lower percentiles of the wage distribution, up to the 10th percentile and possibly a little higher, but not as high up as the median.

The minimum wage has been a major success in raising the pay floor, and recent work by the Centre for Economic Performance and the Resolution Foundation for the Economy 2030 Inquiry believe it could go even further, recommending setting a new ambition for the minimum wage to reach 73 per cent of median pay (£14 on current forecasts) by 2029, while recognising the need for the Low Pay Commission to remain vigilant to the danger of significant employment effects.

Low earners are currently four times as likely as high earners to experience volatility in their hours or pay, or to be working fewer hours than they would like.

But, while the minimum wage has been a success story, the Inquiry’s final report warns that the job satisfaction of the lowest earners has fallen, and emphasises the non-wage dimension of a desire for decent and fair work. Low earners are currently four times as likely as high earners to experience volatility in their hours or pay, or to be working fewer hours than they would like.

Proposals from the inquiry therefore include the right of workers to have a contract enshrining minimum hours that reflect their usual work pattern, employers being required to provide two weeks’ advance notice of shifts and tightening up protections against unfair dismissal and improving sick pay.

The national minimum wage has been highly successful in raising wages, and in reducing inequality. Its first 25 years have shown us what is possible, but there is still more that needs to be done to generate both decent work and wages for all.

This is an edited and updated extract from the 2024 LSE Public Policy Review paper Wage Controversies: Real Wage Stagnation, Inequality and Labour Market Institutions.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: LCV on Shutterstock