There has been extended discussion over the different types of agreement between Labour and the SNP that would enable Ed Miliband to become Prime Minister after May 7th. In this post, James Dennison suggests an alternative scenario in which Labour forms a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, while relying on the support of the SNP as a ‘silent’ partner.

What makes this election so intriguing is not just how close it is but that it is not even clear that the formation of any government will be possible. As things stand, it is uncertain whether a coalition of any two parties will be able to form a working majority. It does, however, seem likely that the consent of the SNP will be required somehow in the formation of the government. In this article, I propose that neither a formal coalition nor a traditional confidence and supply arrangement may be as advantageous for either Labour or the SNP as an alternative type of agreement in which the SNP acts as a ‘silent partner’ in a Lib-Lab government in exchange for greater powers for Scotland.

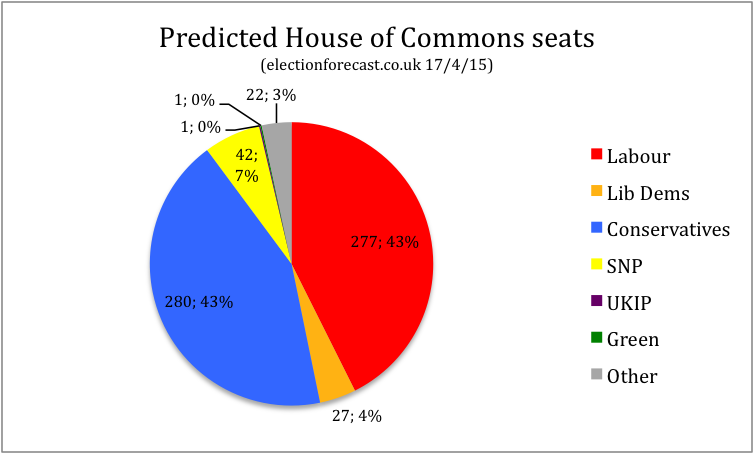

The House of Commons has 650 seats, meaning that for a government to have a working majority, they need to have the support of 326 MPs. However, given that neither Sinn Fein nor the Speaker of the House actually vote, 323 seats results in a working majority. According to electionforecast.co.uk, there is currently a 94% chance that no single party will pass this threshold in May. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 1, the predicted seats in the House of Commons make any two party coalition or confidence and supply arrangement unlikely.

Figure 1. Predicted seats after the general election

The only possibility of securing a majority – besides the unthinkable Con-Lab coalition – is if one of the two major parties includes the Scottish National Party in their arrangements. However, Nicola Sturgeon, the SNP leader, has long ruled out any deal with the Conservatives. Furthermore, a formal Labour-SNP coalition, in which the SNP sits in the cabinet, was already widely viewed as unlikely before Ed Miliband ruled in out in the last leader’s debate. This is unsurprising given that allowing a nationalist party into the government would be electorally disastrous in the future for Labour while the SNP would not want to be in a position where they have to defend Westminster policies to their electorate. Furthermore, the use of Scottish MPs to secure a majority for a part-SNP British government would add insult to the injury of the West Lothian question.

A second, more likely, possibility is that of a confidence and supply arrangement in which the SNP supports a Labour minority government on votes of confidence and appropriation bills, in exchange for the backing of certain SNP policies. This is an arrangement that has recently been used in both the Australian and New Zealand House of Representatives.[1] This would be problematic for at least three reasons. First, Labour would still not have a majority in the House of Commons for parliamentary business besides confidence and supply, meaning that ad hoc agreements would have to be made with other parties. Second, the SNP would still be free to vote against the government on all matters not related to confidence or supply, further undermining the stability of any agreement and perhaps leading to a paralyzed government that, because of the Fixed Parliaments Act, would be likely to survive five years. Third, a minority Labour could also require the consent of the Conservatives on issues such as austerity, which the SNP has vowed to fight. Fourth, a minority Labour government would constantly be vulnerable to the charge that they are propped up by anti-Unionist, ‘anti-English’ nationalists. In short, a confidence and supply arrangement would be unstable because of the lack of a consistent majority and unpopular because the government would be visibly voting alongside the SNP.

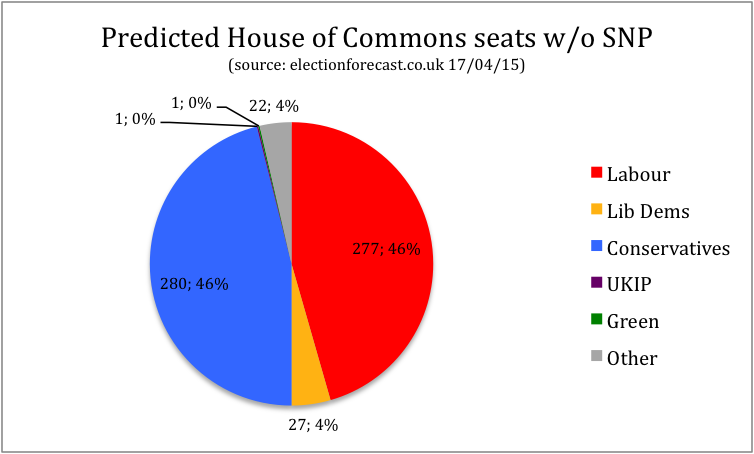

For these reasons, I believe that a third possibility in which Labour is the senior coalition partner, the Liberal Democrats are the junior coalition partner and the SNP are the ‘silent’ coalition partner may be more advantageous for all. In exchange for more powers for Holyrood and promises on public spending and Trident, the SNP would agree to simply abstain on all House of Commons votes for the remainder of the next Parliament. The threshold for a majority would then be lowered from 323 to around 300. As shown in Figure 2, a formal, more stable Liberal-Labour coalition government would then be able to command a slim majority without needing the support of the SNP.

Figure 2. Predicted seats in the House of Commons after May, not including SNP seats

The advantages of a ‘silent partner’ arrangement are numerous and specific to this unprecedented political stalemate. First, the SNP is in a unique position of being a potential party of government that can enact policies better in another legislature, i.e. the Scottish Parliament, than they can in the House of Commons. In the Scottish Parliament, they currently have an absolute majority and are set to repeat that feat at the next Scottish elections in 2016. Therefore, as a party that has traditionally been uninterested in policy outcomes in Westminster anyway, their most logical move is to use their position in the Commons to leverage the maximum amount of devolution for Scotland. The next Prime Minister could frame giving Scotland additional powers very early in the next Parliament as nothing more than the execution of ‘The Vow’, to which all three major parties agreed. Second, the SNP would be able to claim that they are responsible for keeping Cameron out of Number 10. Third, by washing their hands of Westminster, events in the Houses of Parliament will become increasingly irrelevant to the Scottish public. The SNP could effectively decamp back to Edinburgh and concentrate on an empowered, devo-max Holyrood where they alone govern and avoid voting for the austerity programme of the next government.

The advantages of the ‘silent partner’ arrangement are numerous for Labour and the Liberal Democrats as well. First, Ed Miliband would not only want the silent partner SNP to keep as quiet as possible, but also to remain unseen to the English public at key events like Prime Ministers’ Questions and potential confidence and supply votes. This arrangement would see the Commons entirely free of the SNP. Second, unlike the SNP, the Liberal Democrats now have a track record of being dependable and consistent coalition partner. A stable and popular coalition with the Liberal Democrats is far more likely than one with the SNP or a minority government in which Labour has to regularly plead with the Conservatives or Liberals for support. Third, the silent partner arrangement would see English votes for English laws (or at least non-Scottish votes for non-Scottish laws) instituted de facto rather than the Conservatives de jure plans, overcoming West Lothian-esque criticisms. Ironically, the number of MPs would effectively be reduced from 650 to 600 – a previous policy goal of David Cameron. Finally, for the Liberal Democrats, staying in government would keep them relevant and they may be able to gain popularity if a post-Cameron Conservative Party moves to the right.

Of course, many potential permutations and governmental arrangements are still possible, not least because there is likely to be some movement in the polls before election day. However, one possibility that has so far been overlooked is a British government in which Labour are the senior coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats are the junior coalition partners and the Scottish National Party are the silent coalition partners. If the outcome on the 7th of May allows for it, this arrangement could be the most stable and popular for all three parties involved.

Notes: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the General election blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

[1] An interesting copy of a ‘confidence and supply’ agreement between New Zealander parties can be found here.

James Dennison is a PhD Researcher at the European University Institute and a Junior Visiting Scholar at Nuffield College, Oxford. His research interests include political participation, British and European politics and longitudinal methods. He is currently the Research Assistant on a British Academy funded project regarding the 2015 general election.

James Dennison is a PhD Researcher at the European University Institute and a Junior Visiting Scholar at Nuffield College, Oxford. His research interests include political participation, British and European politics and longitudinal methods. He is currently the Research Assistant on a British Academy funded project regarding the 2015 general election.

The suggestion here is one which, in a perfect world, would deliver real benefits for all sides. Sadly, I think for the SNP the idea of staying silent would be a disaster – the link to Sinn Fein not taking up their seats is too easy to make.

However, if they can frame their activity in the context of:

a) Ensuring that ‘the Vow’ is kept

b) Voting only on matters relevant to Scotland that Holyrood can’t control

c) ‘Keeping an eye’ on Westminster

It could work. Kicking the Tories out of No.10 is a huge bonus and ironically there’ll be a positive response from English voters and those who want EVEL. A self-policing answer to the West Lothian question which retains the power for the SNP to renege on the deal if Scotland is slighted.

Where does this leave Plaid and the other Welsh MPs though?

It’s an interesting theory and not without merit constitutionally.

But politically speaking, after 300 years of being told to stay silent and being on the cusp of finally ridding themselves of the semi-literate Labour lobby fodder, are the Scots really going to be in a mood to stay ‘silent’ after electing their strongest voice ever inside the British state?