With the recent accusation that Michael Gove has been sending ‘mixed messages’ over academy schools, it is clear that the policy is still very controversial. Stephen Machin and James Vernoit take a step back and compare the academy schools created by Labour with the new ‘coalition academies’ that have either opened this autumn or applied for academy status since May, and finds the latter are likely to reinforce advantage and exacerbate existing inequalities.

With the recent accusation that Michael Gove has been sending ‘mixed messages’ over academy schools, it is clear that the policy is still very controversial. Stephen Machin and James Vernoit take a step back and compare the academy schools created by Labour with the new ‘coalition academies’ that have either opened this autumn or applied for academy status since May, and finds the latter are likely to reinforce advantage and exacerbate existing inequalities.

The education policies of the coalition government have reawakened controversy about academies, stemming largely from the changing aim of the academies programme under the new government’s plans to significantly expand the academies programme significantly. To do so, it initially asked every headteacher in England if they would be interested in academy status. By 31 August 2010, 170 mainstream schools had made an application to convert to academy status. Progress has been rapid, and 31 of these schools have had their application accepted and started operating as academy schools in September 2010.

The gradual introduction of academy schools into England’s educational system has been a controversial policy innovation. Supporters passionately believe that academies can make a real difference to pupils’ educational outcomes, while critics claim that they are just a way of privatising the state education system by stealth. But who is right – and what impact will the coalition government have on academy school policy?

Academies are independent, non-selective, state-funded schools that fall outside the control of local authorities, and are managed by a private team of independent co-sponsors. The sponsors then delegate the management of the school to a largely self-appointed board of governors.

An academy usually has around thirteen governors, with seven typically appointed by the sponsors. Each governing body is responsible for employing staff, agreeing pay and conditions of service with its employees and deciding the school’s policies on staffing structure, career development, discipline and performance management.

The first clutch of academies was opened in September 2002 by the Labour government with the clear policy aim of improving educational outcomes in deprived areas. Poorly performing schools were awarded academy status by taking over or replacing schools that were either in special measures or seen as under-achieving. The hope was that the combination of independence to pursue innovative school policies and curricula, with the experience of the sponsor, would enable academies to drive up the educational attainment of their pupils.

The performance of academy schools

We evaluated the performance of academy schools by comparing them with a selected group of schools that are due to become academies in the future but have yet to make the full transition to academy status. The latter group consists of schools that are very similar in their pre-academy characteristics to the those of schools that have already become academies.

We believe that, with careful statistical analysis, these ‘future academies’ can allow us to see what would have happened to the current academies had they not become academies. A comparison of the performance of the current academy schools, both before and after they became academies, with the future academies over the same time period, enables us to identify the impact of academy status on the performance of the school.

Our preliminary results show that academies that have been open for at least two years have been able to generate a significant improvement in their GCSE performance compared with the future academies. We find that an extra 3 per cent of pupils in the academies are achieving at least five or more grades A*-C at GCSE/GNVQ compared with the schools that have not yet become academies.

For the academy schools that have been open for a shorter time than two years, we do not find any significant improvement in GCSE performance. This may explain why an earlier study was unable to find any positive effects of academy status on pupil achievement.

Overall, these results suggest that academy schools can deliver faster gains in GCSE performance than comparable schools. Given the preliminary nature of these findings, we are reluctant to draw too strong a conclusion. But it does seem that converting to academy status – at least under the Labour government’s model of converting disadvantaged schools to academies – may actually deliver significant improvements in GSCE performance. At the same time, we need to be patient for any performance enhancing ‘academy effect’ to emerge.

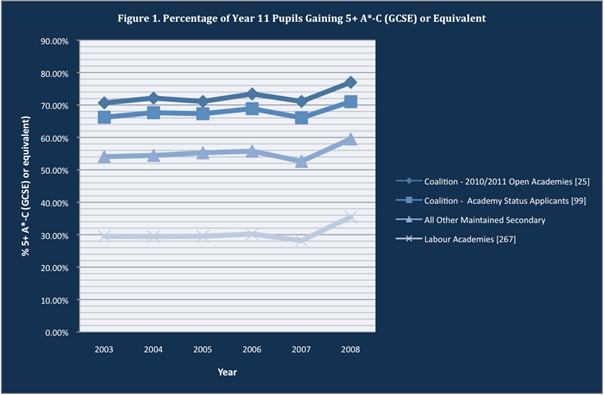

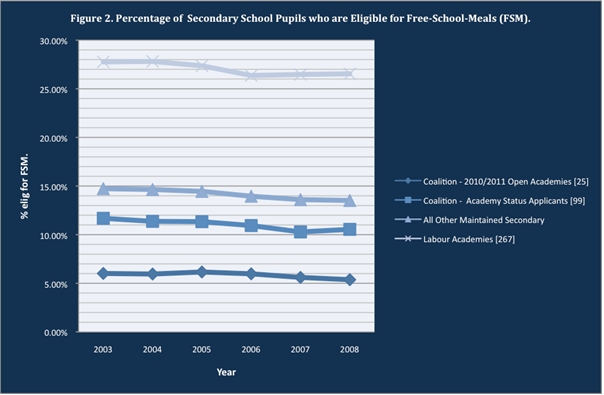

Figures 1 and 2 compare the characteristics of secondary schools that were approved to open as academies under the Labour government with those that have been approved by the new government. Also shown are the characteristics of schools that have applied to the new government for academy status and all state secondary schools.

Number of Academies in [.]. The Labour Academies opened on the following academic years: 02/03 – 3 opened, 03/04 – 9 opened, 04/05 – 5 opened, 05/06 – 10 opened, 06/07 – 19 opened, 07/08 – 37 opened, 08/09 – 47 opened, 09/10 – 73 opened, 10/11 – 64 opened.

Number of Academies in [.]. The Labour Academies opened on the following academic years: 02/03 – 3 opened, 03/04 – 9 opened, 04/05 – 5 opened, 05/06 – 10 opened, 06/07 – 19 opened, 07/08 – 37 opened, 08/09 – 47 opened, 09/10 – 73 opened, 10/11 – 64 opened.

Figure 1 shows the academic performance of the different groups of schools, as measured by the proportion of children achieving five or more A*-C GCSE passes. Figure 2 shows an indicator of deprivation in the different groups of schools, the proportion of pupils who are eligible for free school meals.

It is clear from this evidence that the academies that opened in September 2010 – and the schools that have applied to the coalition government to become academies in due course – are significantly more advantaged than the average secondary school. They are even more advantaged compared with those schools that were approved to open as academies under Labour.

The ‘coalition academies’ contain far lower proportions of pupils who are eligible for free school meals, and they are considerably better performing schools in terms of GCSE results.

Following the change of government, there has been a U-turn in academy schools policy. Under the Labour government, the programme was aimed at combating disadvantage, and we find evidence that it may actually have achieved this objective in schools that have had academy status for a long enough period.

Under the coalition government, the academies programme is now likely to reinforce advantage and exacerbate existing inequalities in schooling. At a time of budget restraint, it seems natural to question whether the large expenditure involved in converting these advantaged schools to academies is justified.

Further reading

Stephen Machin and James Vernoit (2010) ‘A Note on Academy School Policy’, CEP Policy Analysis

Stephen Machin and Joan Wilson (2009) ‘Public and Private Schooling Initiatives in England’, in Rajashri Chakrabarti and Paul Peterson (eds) School Choice International: Exploring Public-Private Partnerships, MIT Press

This article first appeared in the autumn issue of the Centre for Economic Performances’ magazine, Centrepoint.

Click here to respond to this post.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

1 Comments