Only two years ago people were talking of a ‘smashed glass ceiling’ in relation to women’s representation in Whitehall. But female representation has stalled since 2010 as a result of austerity and the failure to prioritise the diversity agenda in recruitment. Daniel Fitzpatrick, Claire Annesley, Francesca Gains and Dave Richards argue that if gender equality in the Senior Civil Service is not addressed as a priority, a climate of complacency is likely to undo many of the gains made since 1999.

Recently, there has been a spate of articles detailing the Coalition’s perceived problem with women in both Whitehall and Westminster. In the vanguard were the Daily Mail, Daily Telegraph and The Times, newspapers not immediately associated with trumpeting gender or equality-related issues. Media plurality was later restored by the Daily Express in the guise of Ann Widdecombe, who waded in with some counter-veiling musings.

The banner headlines were prompted by recent revelations attesting to the poor and falling numbers of women now operating at the centre of Whitehall. In the Civil Service and Diplomatic Service there are currently only 27% female permanent secretaries. Elsewhere, only 27 out of 140 ambassadors are women, with similar patterns also emerging in relation to politically appointed Tsars and special advisers. Looking more widely across Government, the picture is much the same. As one of the co-authors of this blog, Claire Annesley recently observed, there is an absence of women serving on the front bench, in key cabinet committees, or even as committee chairs; all compounded by the still dismally low number of female MPs serving in Parliament.

Yet, if our sights are narrowed back on to Whitehall, only two years ago people were talking of a ‘smashed glass ceiling’. The senior civil service (SCS) was held up as a beacon of gender equality in contrast to the boardrooms of the private sector. Why then today, in more austere and less assured times, has the mood music changed? And why, after more than decade of concerted progress, is diversity in Whitehall (and gender equality in particular) again securing negative headlines?

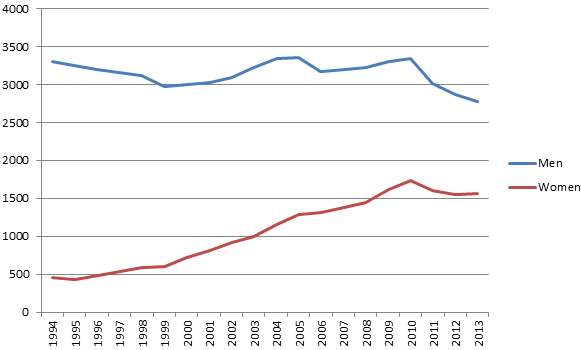

The idea that Whitehall has a white male bias is longstanding in studies of the UK civil service. New Labour identified the homogeneity of Whitehall as a key problem to be tackled in the 1999 White Paper Modernising Government. The figures show that the subsequent diversity agenda, spearheaded by then cabinet secretary Gus O’Donnell, was in relative terms, a success story; there had been a gradual narrowing in the gender gap of the SCS, as well as the rest of the civil service. Table 1 below charts the steady improvement of the gender balance of the SCS between 1999 and 2013.

Table 1: Gender Convergence in the SCS 1999-2013

In 1999 women represented just 17% of the SCS but by 2010 this had risen to 42%. The pinnacle of this achievement was the point of parity reached between the number of male and female permanent secretaries [Grades 1/1a] in 2011, at least among the 16 key government departments. However, that ‘symbolic moment’ of gender equivalence at permanent secretary level has not been maintained. And, if we draw back from focusing on the peaks of Whitehall, there’s evidence that gender representation below Permanent Secretary level has also slipped backwards with 2013 figures showing that women form 36% of the SCS.

Why has the upward trend in female representation in the ‘Top 200’ been arrested post 2010? A number of explanations can be found. The impact on austerity on the civil service is an obvious point of departure. Whitehall is very different place in austerity. The Coalition’s promise to create a ‘leaner, faster government’ will result in one in four officials leaving the civil service by 2015. It is the very top and the very bottom grades that have been proportionally cut the most. Accounting for just 1% of the civil service, the SCS has been reduced by 13% compared with 12% overall. Reductions in headcount are reshaping key Whitehall departments, particularly DCMS, DCLG and Defra. This has inevitably led to higher workloads, which in addition to a wider climate of Coalition and media criticism have culminated in creating ‘really difficult pressures’ for senior officials. Some departments have now started to offer ‘resilience training’ to equip senior officials with the attributes to do ‘more with less’.

Ursula Brennan, the permanent secretary at the Ministry of Justice, has suggested ‘a perceived atmosphere of recrimination at the top of the organisation’ is putting some Whitehall officials off applying for promotion. Brennan has argued that women in particular ‘don’t find it attractive to work in an environment where there’s a lot of criticism, unattributable briefings and that kind of thing’.

Depressed morale and pressured working environment aside, the fall in headcount in the SCS could have been seized as an opportunity to narrow the gender gap in the Top 200 rather than leading to a reversal in the number of female senior appointments. The absence of any discernible recruitment strategy in the context of cuts to personnel suggests that a leadership vacuum was created in Whitehall after 2011 in the post-O’Donnell era. Without a clear lead on the diversity agenda there is a sense that ‘equality is a luxury for the good times’, in which the impact of restructuring on diversity is an afterthought for some departments.

Others have pointed to longer-term issues with ‘talent management’ in the Civil Service and the ‘leaks’ and ‘cracks’ in the pipeline of promotion for female candidates. Although parity was achieve between male and female permanent secretaries in 2011, one rung below at director-general level the skewing towards men remains decidedly pronounced and gets no better the further down the SCS pyramid one looks. Concerns about the future trajectory of women in the SCS has promoted the civil service’s Senior Leadership Committee (SLC) to commission a series of focus groups to identify the barriers that senior female officials believe are hindering them in their attempts to reach the very top posts. Identifying and removing these barriers are critical to addressing the gender gap in the Top 200. However, given that the majority of new entrants to the Top 200 have tended to be external recruits in recent years, the focus on internal talent management is only one part of the problem (see Table 2).

Table 2: New entrants to the Top 200 per year—percentages of external and internal recruits

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| New Top 200 entrants recruited externally | 14 (40%) | 22 (61%) | 15 (52%) | 18 (60%) | 21 (54%) |

| New Top 200 entrants recruited internally | 20 (57%) | 14 (39%) | 14 (48%) | 11 (37%) | 18 (46%) |

| Unknown | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 35 | 36 | 29 | 30 | 39 |

Whitehall does not exist within a vacuum. The drop-off in the appointment of women to senior roles within the wider public and private sectors means that the SCS has a smaller pool of female talent to draw on externally as well as internally. In reality, the impact of austerity on gender representation and equality is a problem for the UK economy and society as a whole. The changing nature of Whitehall means that the diversity agenda needs to be reflected in its approach to external as well as internal recruitment. The UK is still well short of the numbers required to reach the target, set by Lord Davies in his 2012 report, of a quarter of board posts being filled by women by 2015.

Precisely because of this shortfall it is even more important than the issue of gender equality in the SCS is addressed as a priority. If not, a climate of complacency is likely to undo many of the gains recently made. The fear here is that what is taking place is the re-emergence of what Trevor Philips, the former Chair of the Commission for Racial Equality referred to more than a decade ago as a ‘snowy peak syndrome’ across both the UK’s public and private sectors. By this he was alluding to a metaphorical mountain representing an organisation’s workforce. ‘At the base you find large numbers of women and ethnic minority workers whereas at the summit you find a small amount of white, middle class men’. The re-appearance of such snow-bound mountains in 2014 is a chilling thought, particularly in this current season of such inclement weather!

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Daniel, Claire, Francesca and Dave are all members of the Whitehall@Manchester network group.

Dr Daniel Fitzpatrick is a Research Associate in Politics at the University of Manchester

Dr Daniel Fitzpatrick is a Research Associate in Politics at the University of Manchester

Claire Annesley is Professor of Politics and Director of Research in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Manchester.

Claire Annesley is Professor of Politics and Director of Research in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Manchester.

Francesca Gains is Professor of Public Policy at The University of Manchester.

Francesca Gains is Professor of Public Policy at The University of Manchester.

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Manchester.

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Manchester.

The fact that there is both a political and media emphasis on improving diversity in Whitehall only serves as a partial solution to what is a much bigger problem with politics and, in particular, political representation.

If we have a positive discrimination policy for more women, more race & cultures… etc, will this do nothing anything to amend a Parliamentary system in desperate need of change in order that it can ‘serve’ its people better?

A case for improvement is not a personal one, it is a Parliamentary one. For example, given that MPs have No Legal or Statutory Obligation to Represent anyone and are based on a system that FAILS to quantify successful outcomes in MP representations and FAILS to measure MPs performances in their Representations of constituents, does it not therefore questions why there was a political decision to hold teachers, GPs, nurses… etc to account in ‘performance measuring’ targets? If it is Good or Right for nurses, GPs and teachers to have such a vital performance related system aimed at exceeding targets and performance in care and outcomes, why is it not Good and Right for MPs to also have such a system?

Another reason why many may see my observations as a viable proposal for both change and progress in how Parliament and MPs support the vast challenges – even policy failings that hinder people’s lives and undermine a worthy cause to improve community development, is that MPs are paid £67,000.00 a year.. and are not measured for their quality or performance. Many will ask, how can this be right?

So, let’s not talk about given Power to politicians and leaving ‘people’ undermined and lacking empowerment. Let’s do what is tough, but what is right. Change the Parliamentary system – a goal that Mr Cameron did promise at the previous election. Let’s promote a policy that does all of the above positive and democratic things I have mentioned above. Additionally, let’s give the Parliamentary Ombudsman the policy remit to conduct an investigation into any claims of weak or insufficient representation they receive from MPs. This would Empower people, and stimulate a much more progressive attitude by MPs that ‘raise the game’ in their work… and unsettle the weaknesses in the political landscape where people failings are the result of weaknesses in policy development in Parliament.

Its time we stop focusing on the type of individual and build a platform worthy of the democratic value we are meant to be upholding.