‘Angry voters turn to anti-politics of Nigel Farage’, the FT reports. Scotland’s ‘No’ campaign tried to scare people into voting against independence, Alex Salmond argued. Such statements are not rare. When explaining how people vote, we often turn to emotional explanations, and usually we don’t mean this as a compliment. Instead, saying that people’s decisions are emotional is used to de-legitimize these choices. Yet the role of emotions – also known as affect – in our actions and behaviour is more complex than this. As Markus Wagner makes clear in this post, recent research on emotional responses and political decisions has helped to give better answers to why our feelings are important for what we think and how we vote. He then provides evidence for the effect of two key emotions – fear and anger – on voting behaviour during the 2010 election, with particular reference to the financial crisis.

‘Angry voters turn to anti-politics of Nigel Farage’, the FT reports. Scotland’s ‘No’ campaign tried to scare people into voting against independence, Alex Salmond argued. Such statements are not rare. When explaining how people vote, we often turn to emotional explanations, and usually we don’t mean this as a compliment. Instead, saying that people’s decisions are emotional is used to de-legitimize these choices. Yet the role of emotions – also known as affect – in our actions and behaviour is more complex than this. As Markus Wagner makes clear in this post, recent research on emotional responses and political decisions has helped to give better answers to why our feelings are important for what we think and how we vote. He then provides evidence for the effect of two key emotions – fear and anger – on voting behaviour during the 2010 election, with particular reference to the financial crisis.

There are three key insights from the literature on emotional responses and political decision making. First, emotions are always with us: we cannot remove emotions from the way we think and act. Second, emotions drive our behaviour. They provide motivations for our actions and shape what we focus on and think about. Third, this means that emotions shape our capacity for deliberation. Depending on our affective state, we reach decisions differently. For instance, anxious individuals are more likely to consider evidence carefully than those who are angry. When we’re mad, we’re more likely to take rash decisions we’ll regret later on. Another example is strong enthusiasm (‘irrational exuberance’): this can lead us to pay insufficient attention to challenging information.

One way to look at the influence of emotions is to consider the last UK election in 2010. The defining event in that election was the financial crisis, which began in 2007 with the bank run on Northern Rock and which consumed Brown’s premiership. It is not surprising that people had emotional reactions to these developments. Data from the British Election Study from 2010 give an indication of how angry and afraid people were.

Survey participants were given a list of eight emotional terms from which they could tick four. 63 per cent chose ‘uneasy’, 50 per cent ‘angry’, 39 per cent ‘disgusted’ and 31 per cent ‘afraid’. Anger and disgust are usually seen as close relatives, as are unease and fear. Less than ten per cent of participants ticked ‘no feelings’ or ‘don’t know’

Anger and fear are usually seen as the most important negative emotions, and both were prominent in reaction to the crisis: many people were angry, many were uneasy or afraid – and, of course, some were both.

These emotional reactions influenced how voters took decisions in the 2010 elections. Let’s take those who voted Labour in 2005. Many of these voters did not cast their ballot for Labour in 2010 – according to the British Election Study, 45 per cent of them switched parties or did not vote. Why did these voters take these decisions? Emotional reactions to the financial crisis provide part of the answer.

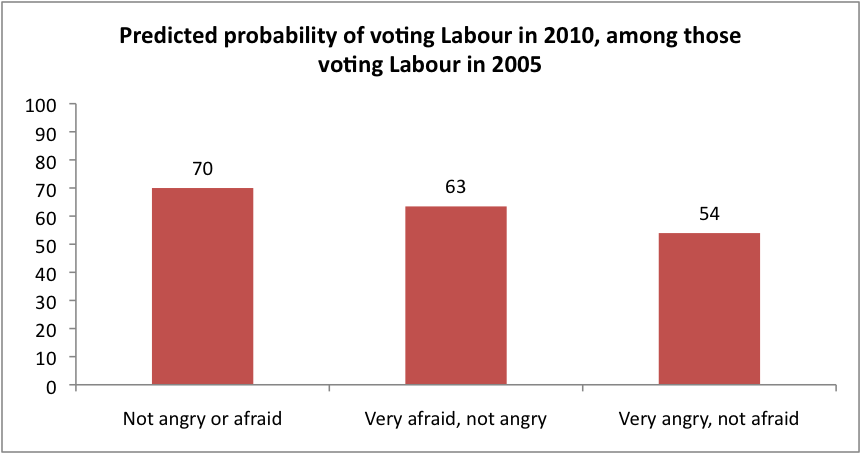

Previous Labour voters who were angry about the financial crisis were a lot less likely to stick with Labour than others. To test this, we can look at the results of a regression model that predicts whether people who chose Labour in 2005 voted Labour again in 2010. The main predictors are negative reactions to the financial crisis: anger and fear. The model controls for emotional predispositions, partisan leanings and economic evaluations because emotional responses (and answers to survey questions about emotions) may themselves result from other attitudes and opinions.

The predicted probability of an angry Labour voters choosing Labour again was 54 per cent, compared to 70 per cent for those who were neither angry nor afraid. Those who were afraid were also more likely to switch to another party – they only had a 63 per cent probability to stick with Labour – but the effect of fear is smaller than that of anger and far less certain from a statistical perspective.

This pattern makes sense given the differences between anger and fear. Anger is said to activate the approach system, which leads individuals to attempt to remove the source of harm. For some people, the source of harm may have been the Labour government. In contrast, fear activates the surveillance system, which leads to risk-averse behaviour. This would explain why people would stick with the government they know and the party they already supported last time.

How might emotional reactions shape voters’ choices in 2015? Issues and candidates will no doubt cause important emotional responses. Voters may be angry about immigration or about stagnant wage growth. They may be afraid of perceived Islamist threats, potential exit from the European Union or the possibility that Nigel Farage will become an even more important political player. Emotions will be a part of how people will think about the elections and how they will reach their decisions.

Yet, one idea we should get away from is that people vote UKIP simply because they are angry or Tory because they are afraid. Gaining electoral success is not simply a matter of manipulating voters into experiencing the kind of emotions that will benefit one’s party. Emotional voters are not unthinking, unreflecting individuals guided by instinct.

Instead, we can think of emotions as shaping how we engage with politics. Enthusiasm can make voters turn out and mobilise others. Fear and unease can make people consider our options carefully and look for the party that best matches their interests. Anger can make voters eager to accomplish change through the ballot box. In any case, it is not a question of emotion or reason, but of how emotions and reason work together to mould our behaviour.

Markus Wagner is an Assistant Professor in Quantitative Methods at the University of Vienna. This blog post is based on results from ‘Fear and Anger in Great Britain: Blame Assignment and Emotional Reactions to the Financial Crisis’ (Political Behavior, 2014). The post is also based on ‘Too scared to switch? why voters’ emotions matter’, a chapter in Philip Cowley and Robert Ford (eds.), Sex, Lies and the Ballot Box: 50 things you need to know about British elections, London: Biteback.

Markus Wagner is an Assistant Professor in Quantitative Methods at the University of Vienna. This blog post is based on results from ‘Fear and Anger in Great Britain: Blame Assignment and Emotional Reactions to the Financial Crisis’ (Political Behavior, 2014). The post is also based on ‘Too scared to switch? why voters’ emotions matter’, a chapter in Philip Cowley and Robert Ford (eds.), Sex, Lies and the Ballot Box: 50 things you need to know about British elections, London: Biteback.

1 Comments