The claim that nearly half of all US jobs are at risk of being automated has been repeated many times. But is it that straightforward? Gavin Kelly offers some facts that moderate the claim. He concludes that although the impact of evolving technology on jobs is currently impossible to predict, there are other, very real issues we should fret about: decreasing productivity levels, stagnant wages, and poor skills.

The claim that nearly half of all US jobs are at risk of being automated has been repeated many times. But is it that straightforward? Gavin Kelly offers some facts that moderate the claim. He concludes that although the impact of evolving technology on jobs is currently impossible to predict, there are other, very real issues we should fret about: decreasing productivity levels, stagnant wages, and poor skills.

We are said to live in an increasingly ‘post-fact’ world but it remains the case that an eye-catching statistic can gain its own momentum and shape public debate regardless of its providence or even its author’s original intent.

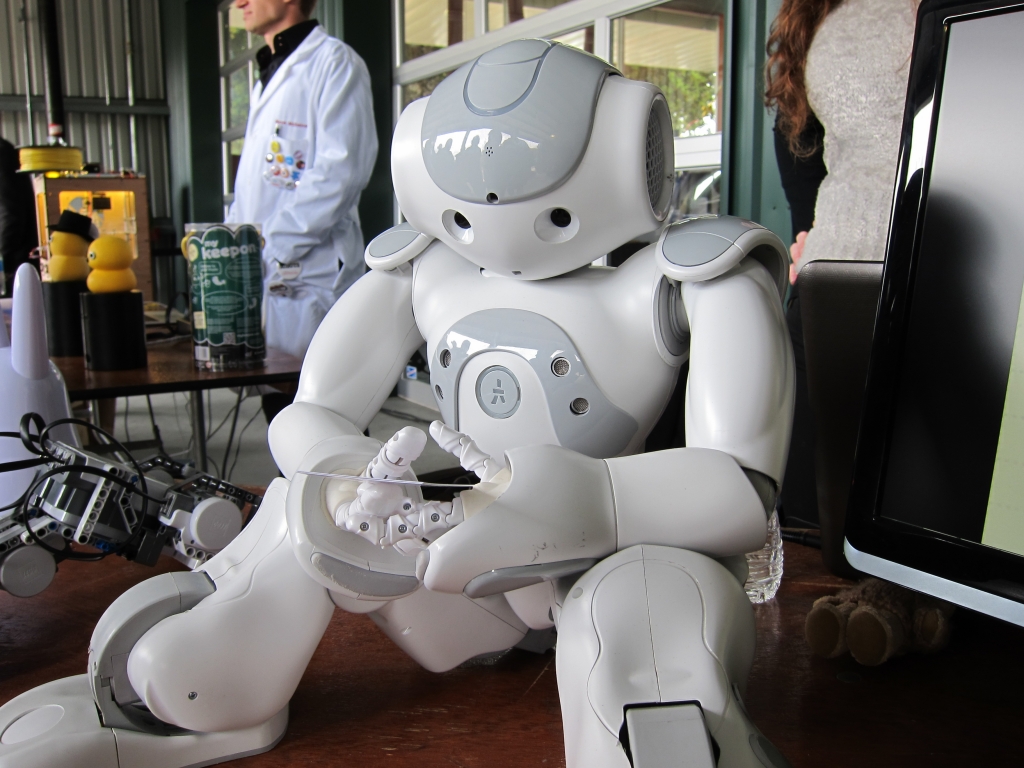

So it is on the question of the rise of the robots and the future of work. It has become a mainstay of public discourse that the world of work is on the cusp of being radically transformed by a wave of job-destroying robotic technology. The killer fact that distils this threat is the oft-repeated finding that 47% of jobs in the US economy are at risk of being automated over the next decade or two. Related studies find that across the OECD 57% of roles are at risk, more still in emerging economies. Hug your job tight.

Politicians, business leaders, and some of our most respected economic institutions have in different ways repeated or replicated these gloomy-doomy conclusions. Our media laps up these findings having a near insatiable appetite for features on how humans are destined for the scrap-heap as they lose out in the race against the machine. Future-gazing pieces speculate about how we will all find meaning when the work runs out. Seminars on designing a welfare state fit for a ‘post-work world’ are all the rage.

Yet seasoned observers of the evolution of jobs markets tend to raise an eyebrow about grand claims about the disappearance of work from large swathes of the economy. And they are more sceptical still when it comes to what sound like spuriously precise estimates of how many jobs are likely to be automated some decades in the future.

That scepticism has now been given concrete form by an important, if predictably underreported, study by the OECD. It replicates much of the original (and, it should be said, thought-provoking) report by Carl Frey and Michael Osborne which produced the ‘47% of jobs at risk’ finding — but it moderates a few vital assumptions.

Rather than assessing the risk that a whole occupation will be replaced by smart-machines the OECD authors instead take a more granular look at the underlying bundle of tasks that make up different jobs, considering how automatable each of them are. The point being that even within occupations that appear ripe for technological upheaval — say, bookkeeping or retail sales — there is much non-routine work that will prove very hard to mechanise in the near future.

This more forensic approach results in a collapse in the estimate of the proportion of US jobs at risk from 47% to just 9% (9% is also the OECD average). Still significant, but a massive down-grade. What’s more, the authors suggest their figures are likely to be an over-estimate of actual job losses. In part because many workplaces are sluggish in utilising new labour-saving technologies and workers performing tasks under threat often find ways of adapting their role so as to complement smart machines. But also because there will be some offsetting employment gains: new jobs get created due to the demand for innovative technology, and tech-induced price reductions mean consumers have more disposable income available to spend on other things.

The correct response to all this isn’t to release a sigh of relief as we switch from believing that only one in ten jobs are at risk rather than one in two. Other studies will surely come along with new estimates. No, the lesson is that we should be highly circumspect about all such claims — especially those with shock and awe headlines — and interrogate the underlying assumptions closely.

None of this is to say that the onset of intelligent machines won’t disrupt all manner of working patterns, including in previously protected white-collar occupations. It would be very surprising if they didn’t: every phase of capitalist development is associated with new technology that triggers the rise and fall of different roles.

The question is whether this time will be so very different? Will this era of shockingly low productivity growth be a precursor to great technological advances that overshadow everything we’ve ever seen before in terms of their jobs-impact? Perhaps. None of us can know. But, as the OECD shows, it’s hard to arrive at that sort of conclusion based on the available evidence.

For now the UK remains a jobs-rich nation. Employment is at a record high and worklessness is less of an issue than it has been for a generation. Yet there are plenty of issues right in front our eyes to fret about: low investment, flat-lining productivity, stagnant wages, poor skills to name a few. Of course, none of these catch the eye like a story on how the march of the machines is destined to make humans obsolete. But, for now at least, they are more real.

___

Note: this was originally published on Gavin’s personal blog and is reposted here with thanks.

Gavin Kelly is the CEO of the Resolution Trust, and the former Director of the Resolution Foundation. He tweets as @GavinJKelly1.

Gavin Kelly is the CEO of the Resolution Trust, and the former Director of the Resolution Foundation. He tweets as @GavinJKelly1.

Mr Kelly, I note that you quote this recent paper from the OECD about potential job losses, and temper it with a degree of warning about there being little consensus, and that we shouldn’t perhaps be quite so worried about immediate jobs losses as the 47% figure previously quoted from Fey & Osborne, because of it.

That is fair enough, but I might suggest that these two reports are probably the far ends of the scale. In any event, we are talking about millions of jobs world-wide, disappearing completely.

I emphasise “completely”. In the past, machines have made people more productive and reduced the number of people required to do the jobs. Now they are going to be replacing the humans doing the jobs altogether. We are already at the point where the jobs available are not meeting the needs of the population. The Governments are hiding this because they don’t want the populations to realise this and demand change.

When you consider the most obvious of jobs that are going to disappear – for those who drive for a living – ask yourself if all of these people are going to be able to adapt to the type of jobs that will arise from the new technology.

As to the “record high unemployment”, this is only possible because the UK taxpayer is subsidising low paid jobs with working tax credits and other tax credits and benefits. There are more on benefits in work than there are on benefits out of work.

You mention stagnant wages, rather than low wages, but “Poor skills” comes back to my point about whether or not those who are on the cusp of losing the job they do to machines are going to have the wherewithal to re-train. This is not just a matter of personal ability, but funding and benefits conditionality. You still have to be available for work. This effectively rules-out a decent full-time course to re-train and get a Level 4 qualification or better (even many Level 3 ones).

What you neglect to touch upon is the validity and language of the statistics – which minimise the number of peoples’ lives affected. Oh yes, 9% as opposed to 47%, is a small percentage of those who may lose their jobs to automation, but aside from arguing the toss over either figure’s accuracy, these numbers still mean that millions of people will be placed permanently out of work. Let’s not forget that the net 5 millions jobs that are estimated as going to disappear by 2020 (http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/davos-2016-more-5-million-jobs-will-be-lost-robots-by-2020-says-wef-study-1538676) is a net figure. (http://uk.reuters.com/article/us-davos-meeting-employment-idUKKCN0UW0NV).

That recent report is also of OECD countries only. Less well developed nations are going to be hit harder by automation.

The other day, 60,000 jobs got lost to robots all at once. https://www.techinasia.com/foxconn-robots-china-job-losses.

These unemployment statistics hide the true numbers of the out of work. We have carers who are looking after family for nothing, not all of whom are supported by spouses or other family in work. The economically inactive in the UK is nearly 9 million. This may include students and house wives and husbands, but many of these people are also looking for work, which they cannot find that fits around their lives. They don’t meet the conditions for unemployment, so are not classified as such.

The UK in particular is hiding the true numbers of unemployed by using ridiculous excuses to kick people off benefit – and sometimes do not even bother with reasons. I know of someone who had their benefits stopped completely in April and still does not know why. No Universal Credit, no money towards the rent, nothing. No reason or explanation given. The call centre could not explain it, and they haven’t had any benefits for two months now despite escalating what was already a complaint about their benefits.

I wonder if they were counted as unemployed? They certainly wouldn’t have been on the last claimant count.

All because the Government is trying to tell the public that it’s welfare reform is working – but it isn’t and they are hiding the truth and rigging the figures, by hook or by crook – so the likes of you can keep on quoting them because they are supposedly trustworthy and true so you can draw false conclusions as a consequence.

You are right to temper both these reports with a degree of caution, but you go too far with the thrust of your article and saying “don’t hold your breath”. These jobs are going to start disappearing fast and are going to have a greater effect than you believe, because no one is going to foot the bill to retrain anyone unless there is a profit to be made. People being made unemployed will be screwed by employers and machines and left to a Government system that makes you apply for jobs you can’t do or are excluded from by the recruitment process or location, or jobs simply already do not exist now, let alone in the not too distant future, and with conditions on their benefits that actually prevents them from getting higher level qualifications, because they would lose their benefits – let alone being able to afford any fees.

Perhaps you consider yourself safe from this, and perhaps you are, but millions are clearly not, and we need to kick people out of their complacency, not reassure them. We are heading for mass unemployment and we need measures in place to protect the unemployed from starvation and death – such as a basic income guarantee and the removal of conditionality towards it.

After all, there is no point worrying about people being lazy (which is a proven and obvious nonsense when you consider it; nobody wants to do nothing forever) and forcing conditions upon them to get paid work, when there is not going to be enough, if any paid work for them anyway.

Whether the jobs of work drop by 9% or 47%, the problem remains the same. The only academic debate about them really is a matter of scale.