Reviewing the first substantial book recording the history of the coalition government so far, this Ipsos MORI authored work paints a very detailed picture on what the parties were doing in the lead up to the election, how voters were responding, and what the polls were showing all the way to the very last count. Carl Packman finds this volume is the closest we can get to understanding the public mood at the time and since.

Reviewing the first substantial book recording the history of the coalition government so far, this Ipsos MORI authored work paints a very detailed picture on what the parties were doing in the lead up to the election, how voters were responding, and what the polls were showing all the way to the very last count. Carl Packman finds this volume is the closest we can get to understanding the public mood at the time and since.

Explaining Cameron’s Coalition: How It Came About: An Analysis of the 2010 British General Election. Robert Worcester, Roger Mortimore, Paul Baines, Mark Gill. Biteback Publishing. May 2011

Explaining Cameron’s Coalition: How It Came About: An Analysis of the 2010 British General Election. Robert Worcester, Roger Mortimore, Paul Baines, Mark Gill. Biteback Publishing. May 2011

The last election, held on May 5th 2010, was one that will not be forgotten for quite some time to come. It was the one which included ‘Bigotgate‘, where Labour’s Gordon Brown was recorded calling an elderly interlocutor a “bigoted woman”. It was also the one the Tories thought they had covered, but only took office with a helping hand from Nick Clegg who, with fellow Liberal Democrat Members of Parliament, entered into a coalition government.

According to the authors of a new book – indeed the first substantial book recording the history of the coalition government so far – it was the election where “pollsters were stumped at the outcome”. And they should know, being the very pollsters, from Ipsos MORI, trying to assess the outcome. This book, from a series of post-election volumes during the Labour years up until now, paints a very detailed picture on what the parties were doing in the lead up to the election, how voters were responding, and what the polls were showing all the way to the very last count.

It doesn’t take a numbers boffin to tell the public that the 2010 election was a success for no political party at all. More voted this time than in the last few years, but no party leader managed to woo voters in the sorts of numbers that leaders from 1945-1997 could expect. Pollsters opined that core votes are on the wane, and politics is fast becoming a game of personalities (exemplified in the interest in leadership debates). Though Brown had negative impacts on public audiences (being seen as stiff, non-personable and leagues away from his predecessor Tony Blair) it has been the opinion of some that this level of public spotlight did David Cameron no favours either. The latter’s blatant upper class appearance may well have given the impression that he is out of touch with the “man on the street”.

Despite today being the Prime Minister, no one would say 2010 was Cameron’s election. The Tories may have achieved 23 gains where the party needed at least a 5% swing (thanks to Lord Ashcroft’s money and research), and Cameron did rate highest in polls, suggesting he looked as though he’d be the most capable leader in a crisis situation, but still he and his party were unable to form a majority government.

Questions inside the Tory party have predictably focused on how Cameron could have done things better. Election poll ratings for the party have greatly reduced, at 40% average in June 2010, to 37% in January 2011 and down to 33% in February 2011. As early as September 2010 the honeymoon period was over – and that’s before the cuts agenda had been felt significantly on the frontline.

However this is no cause célèbre for the Labour party. 46% of the public vote placed issues on immigration and asylum as of high importance. This is something the Tories always do better on electorally and indeed nothing changed this time around. But there has been a rise in voters suggesting none of the main parties represented their views on the asylum question. With Labour having lost 100 seats and 5 million voters last year, and the level of dissatisfaction with Ed Miliband having doubled from October 2010–February 2011, while Liberal Democrats preside over huge swathes of support lost at the expense of favourable gains by smaller parties such as the United Kingdom Independence Party, we may see many more coalition governments – though we may like to be careful for what we wish for.

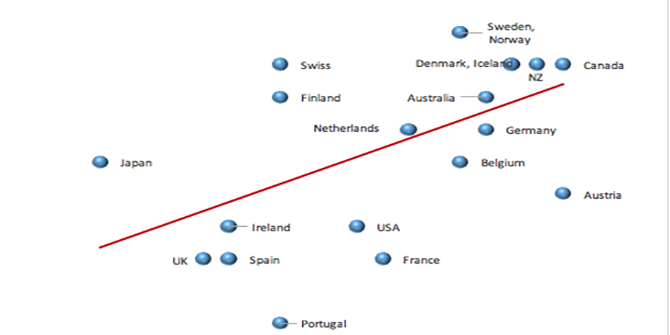

Any criticism of this book inevitably has to do with the way in which polling is conducted. When a member of public is asked who they will vote for, we are merely given a 2-D intention. Polling is unable to show what motivates an individual to vote one way or another. Similarly, through such polls, we have no means to our disposal to measure how reluctant a party’s core vote is (say, Labour party socialists who feel the party has gone too far to the right, or right wing Tories who feel their party is too keen on European integration) – though this could either be because pollsters haven’t the time or the money, or even because analysts and political parties alike are unsure of who the “core voter” is.

This volume is incredibly helpful for context, and is the closest we can get to understanding the public mood. Though the floating voter is growing in influence as more people become suspicious of politicians (and as the authors admit, pollsters need to get ready for a more complex political landscape), in an Ipsos MORI poll, a measly 13% of people said they had trust in politicians, and another poll by Hansard saw only 22% of the public say they would be proud if their child became an MP. On reading this book one comes to realise it is less about understanding Cameron’s coalition, and more preparing for things to come.

Explaining Cameron’s Coalition: How it came about – An analysis of the 2010 British General Election. Robert Worcester, Roger Mortimore, Paul Baines, Mark Gill. Biteback Publishing. May 2011.

Find this book: ![]() Google Books

Google Books ![]() Amazon

Amazon