Matthew Partridge finds Dick Cheney’s memoir to be candid and honest, charting the former American Vice-President’s glory days of influence in the Bush administration to the now quieter times on the side-lines.

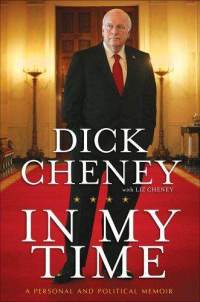

In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir. Dick Cheney. Simon and Schuster. September 2011.

Find this book: ![]() Google Books

Google Books ![]() Amazon

Amazon

Traditionally, the office of American Vice-President has been regarded as a poisoned chalice. While Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson and Gerald Ford inherited the Presidency after the death of the incumbent (or in Ford’s case the impeachment), for others it has been a cul-de-sac in both career and governmental terms. For instance, Al Gore’s attempt to claim some of the credit for the economic success of the Clinton administration only generated ridicule, while Biden has lost several key foreign policy debates. However, there has been one occupant of Blair House who has had a key role in shaping a presidency.

Traditionally, the office of American Vice-President has been regarded as a poisoned chalice. While Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson and Gerald Ford inherited the Presidency after the death of the incumbent (or in Ford’s case the impeachment), for others it has been a cul-de-sac in both career and governmental terms. For instance, Al Gore’s attempt to claim some of the credit for the economic success of the Clinton administration only generated ridicule, while Biden has lost several key foreign policy debates. However, there has been one occupant of Blair House who has had a key role in shaping a presidency.

That person is of course, Dick Cheney. Indeed, his supposed influence on the Bush administration loomed so large in the imaginations of many commentators that he became an almost Svengali-like figure. In W., Oliver Stone’s crude satirical swipe at the Bush years, Cheney was portrayed an oil obsessed megalomaniac, while Barton Gellman’s Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency all but accused him of multitude of crimes, including blackmail. Even more serious academic studies credit Cheney with transforming the office, with Bruce Montgomery arguing, in Richard B Cheney and the Rise of the Imperial Vice Presidency, that he “managed to dominate events and shape world history like to no vice-president before him”.

After a brief introduction giving a narrative account of the events of September 11th, as seen from Cheney’s immediate perspective, the first four chapters deal with his childhood, his education, Cheney’s stint in the Nixon and Ford White Administrations, and his time in Congress. Although Cheney would rise to the senior position of Chief of Staff to President Ford, and would serve on the important Intelligence Committee in the House of Representatives, the relative lack of detail in the chapters implies that his roles were minor and his influence on events and policies peripheral.

The book begins to get more interesting in the next three chapters, which examine Cheney’s tenure as Defense Secretary. His period in control of the Pentagon would coincide with the break-up of the Soviet Union, the liberation of Panama and the first Gulf War. Some questions are left unanswered, such as the extent to which the George H.W. Bush administration was willing to use Kuwaiti territory as a bargaining chip. However, there are also some surprising revelations, such as the fact that America “couldn’t have done much had Saddam decided to keep right on rolling into the Saudi oil fields”, implying that the U.S. would have cancelled troop deployments rather than confront Saddam.

Chapters 8 and 9 serve as an intermission, focusing on Cheney’s time between leaving the Pentagon and becoming Vice-President. Like the earlier chapters, although they contain a few interesting stories, especially regarding the process whereby he became George W. Bush’s running mate, there are no surprising revelations.

The final seven chapters, which cover roughly three-fifths of Cheney’s memoirs, deal with the part of his career that most readers will be interested in, namely his time as Vice-President. As with the section dealing with his time in charge of the DoD, Cheney focuses on several issues, rather than attempting to provide a broad overview. The topics discussed suggest that, although Cheney was involved in some economic issues, such as the budget negotiations in the first year, his influence was mainly felt in national security and foreign policy issues, such as the debate over enhanced interrogation and the war in Iraq.

Unsurprisingly, Cheney remains largely unrepentant about the decisions made, pointing out that many of the supposedly ‘misleading’ statements made by Bush and the CIA may have been correct, a fact frequently overlooked by many commentators. He is also extremely critical of those within the administration who either opposed the war in Iraq originally or wanted a quick handover, once the reconstruction ran into difficulties.

Reading between the lines, the autobiography also appears to show that Cheney’s influence peaked in Bush’s first term. The 2006 mid-term elections, which were disastrous for the Bush administration, seem to have drastically reduced his influence on events. Indeed, his convention-breaking decision in 2008 to give symbolic support to the (successful) legal challenge to the ban on handguns in Washington DC, a policy that the White House was prepared to accept, signalled his relative impotence. His account of the financial crisis later that year, reads like an account from the side-lines, not as a decision maker.

Overall, In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir is a solid work, which although it lacks the detail of Kissinger’s classic multi-volume efforts, or the sense of immediacy provided by Matt Latimer’s Speech-Less, is more candid and honest than other political memoirists of his seniority. It also proves that no matter how powerful, there is a profound difference between being part of the President’s inner circle, and being the President.

Find this book: ![]() Google Books

Google Books ![]() Amazon

Amazon