In architecture and psychology literature there is now growing interest in the negative consequences that commercial signs can have on the visual quality of urban areas and on people’s quality of life. Visual Pollution by Adriana Portella asks what is needed to enhance visual quality in historic and commercial city centres, and includes chapters on consumer culture, marketing the city, and urban tourism. This book is a welcome addition to an emergent field and hopefully it will inform urban policies that focus on the quality of people’s experience of historic city centres, writes Paulo Rui Anciaes.

This review was originally published on the LSE Review of Books.

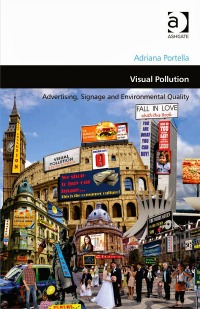

Visual Pollution: Advertising, Signage and Environmental Quality. Adriana Portella. Ashgate. October 2013.

Visual Pollution: Advertising, Signage and Environmental Quality. Adriana Portella. Ashgate. October 2013.

Visual pollution is the poor cousin of urban environmental research. Often dismissed as a policy issue because it is difficult to measure and depends on people’s tastes, it is also subject to far fewer regulations than more tangible environmental problems such as litter, air pollution, and noise. Nevertheless, books such as Marc Augé’s Non-places (1995) and Naomi’s Klein’s No Logo (2000) have raised awareness to the visual quality of the built environment and inspired the work of researchers and activists. For example, during the 1990s, social movements such as Reclaim the Streets held demonstrations to highlight the factors affecting people’s experience of public spaces. More recently, projects such as the Billboard Liberation Front and Brandalism have used “guerrilla art” to challenge the encroachment of consumer culture on public space.

Adriana Portella’s Visual Pollution focuses on the case of commercial signage in historical and commercial city centres. The book’s major contribution is to the field of environmental psychology, studying people’s perceptions and evaluation of different types of public spaces. The main argument is that these aspects are shaped not only by the individual’s characteristics, values, and experiences but also by objective attributes of buildings and commercial signs such as order, complexity, and contrast.

The book reports an empirical study comparing streets in a British city (Oxford) and in a couple of cities in Brazil’s southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul (Gramado and Pelotas). The streets in the three cities have been subject to different types of commercial signage control. The streetscapes in Oxford are monitored by regulations defined at a national level for preserving historic heritage. In Gramado, the streetscapes are the product of local strategies for marketing the city as “the Brazilian Switzerland” and creating what the author calls a manufactured Alpine “themed environment”. The Pelotas city centre has not been subject to any control, resulting in a disordered streetscape.

Given these characteristics, it comes as no surprise that the majority of the respondents in surveys in the three cities like the streets in Oxford streets and dislike the streets in Pelotas. These preferences are analysed in detail in Chapter 6. Here, and throughout the book, the author emphasizes the common perceptions and evaluations of people from different countries and of lay people and professionals working in urban planning and design. The role of those common perceptions and evaluations is not very clear in the case of Gramado. In fact, the preferences of the city’s residents, especially lay people, are influenced by their familiarity with the streetscape and by symbolic meanings attributed to the Alpine-style buildings in their town. At the same time, some Oxford residents do not like Gramado streetscapes because the buildings “do not look Brazilian” (p.188).

Chapter 7 then analyses perceptions and evaluations in terms of a series of objective attributes of buildings and signs. Among other interesting results, we find that building facades with ordered commercial signs are evaluated positively regardless of complexity and colour variation in the streetscape. But when signs are disordered, complexity and colour variation are evaluated negatively.

The book succeeds in finding a set of recommendations to enhance the visual quality of city centres, useful for urban planners, civil engineers, architects, and lawmakers. It addresses the current lack of a general approach to guide the control of commercial signage, by proposing an evidence-based approach based on perceptions and evaluations linked to objective characteristics of streetscapes. It is not very easy, however, to grasp the scope of the evidence collected in the study, as only two small results tables are included in the whole book.

Another strength of the book is the extensive background information provided about theories of perception and cognition of the built environment, legal frameworks to control commercial signage, and the forces shaping the visual quality of public space, such as consumer culture and city centre management and promotion. More information could be given, however, about how building and signage appearance relate to other elements disturbing the visual experience of the city centre, such as vehicles (moving and parked), utility poles and wires, street furniture, and litter.

The analysis also leaves some questions unanswered. The evaluation of the visual quality of buildings depends to a large extent on their state of conservation and on the presence of graffiti – a problem affecting the Brazilian case studies and reaching epic proportions elsewhere in Brazil. The surveys also do not capture the actual effects of visual pollution on people’s wellbeing and behaviour. How does visual pollution make people feel? Does someone avoid going to the local centre or visiting another city because of excessive or disordered commercial signage on buildings?

Despite the subjectivity in the measurement of the magnitude and nature of the problem, the issue of visual pollution is one that is relatively easy to illustrate. The study shows for example that the results obtained using photomontages of street facades views of real places tend to be an adequate substitute of on-site observations. A single image of a street with excessive signage can therefore communicate effectively what the problem is about. So it is slightly odd that the cover of this book is a photo of a couple getting married, among a bizarre collage of monuments and buildings from around the world.

Despite a couple of minor shortcomings, the book is a welcome addition to an emergent field and hopefully it will inform urban policies that focus on the quality of people’s experience of historic city centres.

———————————–

Paulo Rui Anciaes is a researcher at the Centre for Transport Studies, University College London. He completed his PhD. at the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics. Paulo blogs about Community severance and Alternative Environmentalism and contributes to the UCL Street Mobility project blog. Read more reviews by Paulo.