The Brexit vote has not shifted overall opinion on the question of Scottish independence in Scotland. Jan Eichhorn explains why this is the case and writes that, if supporters or opponents of Scottish independence want to use Brexit to their advantage, their best chance is to establish a narrative about its impact on the economy.

The Brexit vote has not shifted overall opinion on the question of Scottish independence in Scotland. Jan Eichhorn explains why this is the case and writes that, if supporters or opponents of Scottish independence want to use Brexit to their advantage, their best chance is to establish a narrative about its impact on the economy.

In the EU referendum, 62 per cent of voters in Scotland chose to remain part of the European Union. And while there was variation in support by area, each count came in with a majority for remain. Knowing this has led several commentators to suggest that support for Scottish independence might rise in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, with the latter becoming the most decisive issue in a potential second independence referendum. However, understanding the interplay between the EU issue and the question of Scottish independence requires both more caution and detailed analysis.

After an initial “boost” of support for independence to 52-53 per cent in three polls in the immediate aftermath of the referendum in June 2016 (don’t knows excluded), levels quickly reversed to the same position the polls were in around September 2014, with support for independence fluctuating between 44 and 49 per cent since July 2016.

Several analyses have explored why the Brexit vote has not shifted overall opinion in Scotland in a consistent manner. As a YouGov study investigation showed, there were people who became favourable to Scottish independence following the vote, however, a roughly similar number of people also changed their view in the other direction and actually became opposed to independence.

As John Curtice has pointed out, the independence movement and supporters of the SNP are actually more heterogeneous than often thought of. A majority of SNP as well as independence supporters favour EU membership, but there are also significant minorities in these groups that favour independence from both the UK and the EU – partially reflective of eurosceptic positions the SNP held in the past.

So, while there are some links between EU and Scottish independence attitudes, the two are not synonymous. This, however, only tells us why the polls stand where they stand. We need some further analysis to understand whether Brexit could become decisive in a second Scottish referendum. To do this, we need to look back to the 2014 vote. EU membership was an often discussed issue by political actors and commentators, with a large inquiry by the Scottish Parliament and interventions from London and Brussels.

However, the idea that EU membership drove most Scots’ decision-making in 2014 – because of their love for Europe – is misguided. Yes, compared to other parts of the UK, Scotland has been and is less negative about the European Union, but it is not a fan of it either. When we take together those who say that the UK should leave the EU and those who say it should stay but that some powers should be returned to member states, the total proportion in Scotland is roughly the same as elsewhere in the UK (about two-thirds to three-quarters). So, while the majority of Scots want to remain, the number of those who like the status quo or want more European integration has not been markedly greater than elsewhere in the UK.

Taking all this together, it is not surprising to find that the question of the UK’s EU membership was not decisive in the 2014 referendum in the aggregate. Both independence supporters and opponents had roughly the same position on the EU on average. For example, about three-quarters in either group agreed that an independent Scotland should be part of the EU. The question did not divide the public as a whole with regards to independence.

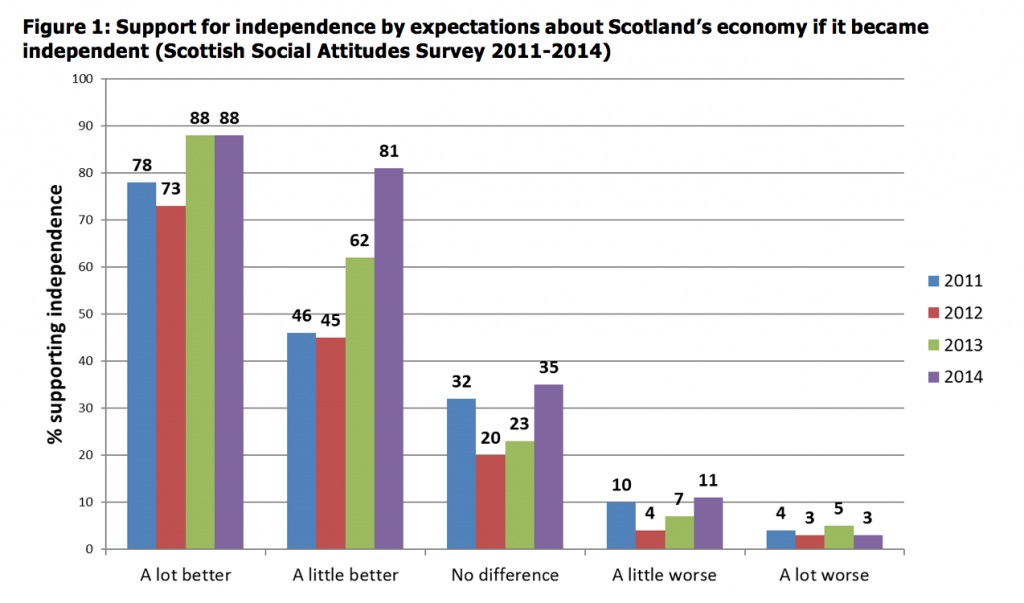

As we demonstrated multiple times, the most important factor associated with people’s decision to vote for or against independence in 2014 was their expectation of whether the Scottish economy would ultimately do better or worse after independence – a relationship that grew in strength throughout the campaign. Nearly everyone who was optimistic about the economic prospects of independence voted in favour and conversely nearly all those sceptical voted against (see figure 1).

What does this ultimately mean for the consequences of Brexit for attitudes towards independence? We have seen that some people in Scotland shifted their views on Scotland’s role in the UK, but crucially in both directions. While a majority who have been sympathetic to Scottish independence also supported EU membership, the same holds true for those opposed to independence. Conversely, there are significant minorities in both groups who do not want to be in the EU – so the EU question does not map directly on independence attitudes.

However there is one avenue that might increase the salience of the issue of EU membership: the link between expectations about the economy and the implications of Brexit. While there is a lot of uncertainty at this point, actual changes in the future may shift views – in either direction. If leaving the EU became clearly associated with expectations of an economic downturn, the economic risks about Scottish independence might be re-evaluated by some. Conversely, if Brexit came to be seen as an opportunity for future economic prospects, Scottish views could shift in favour of the union.

If supporters or opponents of Scottish independence want Brexit to have a high likelihood of impact in a potential second Scottish independence referendum, their best chance is to clearly establish a narrative about its link to the economic question. On its own, EU membership, while generally relevant of course, is unlikely to galvanise massive opinion shifts amongst very large groups of the Scottish public.

Jan Eichhorn is Lecturer in Social Policy (Chancellor’s Fellow) at the Social Policy School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh.

Jan Eichhorn is Lecturer in Social Policy (Chancellor’s Fellow) at the Social Policy School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh.

It’s NOT the economy, stupid! You can’t answer a constitutional question with a calculator.

To quote an ex US president “It’s the economy stupid.”

What I don’t understand about this is that the total number of voters replying ‘a lot better’ to the question “As a result of independence would Scotland’s economy become better, worse, or would it make no difference?” was identical in January 2014 to what it was in January 2011. The numbers relying ‘a little better’ actually DECLINED significantly during that same period, while those answering ‘a lot worse’ INCREASED substantially. So while economic optimism about a post-Indy Scotland actually DECLINED between January 2011 and January 2014, support for Indy INCREASED. (figures from Scottish Social Attitudes surveys here: http://whatscotlandthinks.org/questions/if-scotland-were-to-become-independent-would-economy-would-be-better-worse-or–7#line)

Surely it follows from this that optimist/pessimism as to the economic consequences of a future independence Scotland is NOT correlated to increased or decreased support for, or opposition to, Scottish independence? I think it may be more the case that Yes voters adopted a rationalised, defensive and Panglossian positive attitude to the economic consequences of Indy – and ditto No voters forecast rationalised doom and gloom.