Kieran Wright shows how Scottish Labour adopted a less left-leaning justification for its stance on the constitutional issue in the years after the party lost power to the Scottish National Party. Consequently, the party failed to present itself as a clearly left-of-centre alternative to the SNP and downplayed the progressive case for Scotland remaining in the UK.

Kieran Wright shows how Scottish Labour adopted a less left-leaning justification for its stance on the constitutional issue in the years after the party lost power to the Scottish National Party. Consequently, the party failed to present itself as a clearly left-of-centre alternative to the SNP and downplayed the progressive case for Scotland remaining in the UK.

The outcome of the 2021 Scottish Parliament election will go some way to deciding whether the United Kingdom remains united for much longer. If the Scottish National Party continues its recent run of electoral success, demand for a second referendum on Scottish independence is likely to increase. The SNP’s recent success is due in no small part to the fact that it has been more successful than Scottish Labour in arguing that its preferred answer to the constitutional question is the best route by which Scotland can pursue social democratic policies. Consequently, providing a challenge to this line of argument is essential if Labour is to recapture a significant segment of the support it has lost to the SNP in recent decades.

In my research, I use the language used by elected representatives in sessions of First Minister’s Questions (FMQs) in the Scottish Parliament as an indicator of the strategic approach Labour and the SNP pursued, starting with the very first of those sessions in 2000 and ending with the last session prior to the 2016 Holyrood election. Up to 2007, Labour’s strategy was to frame its stance on the constitutional issue by referencing the party’s progressive identity. It argued that remaining in the UK was the best route to Scotland benefitting from progressive, left-of-centre policies, and characterised independence as a distraction from the pursuit of progressive goals such as tackling poverty. Losing power to the SNP in May 2007 appears to have prompted Labour to alter this strategy and increase the extent to which it questioned the economic viability and desirability of independence rather than the progressive credentials of those who support it.

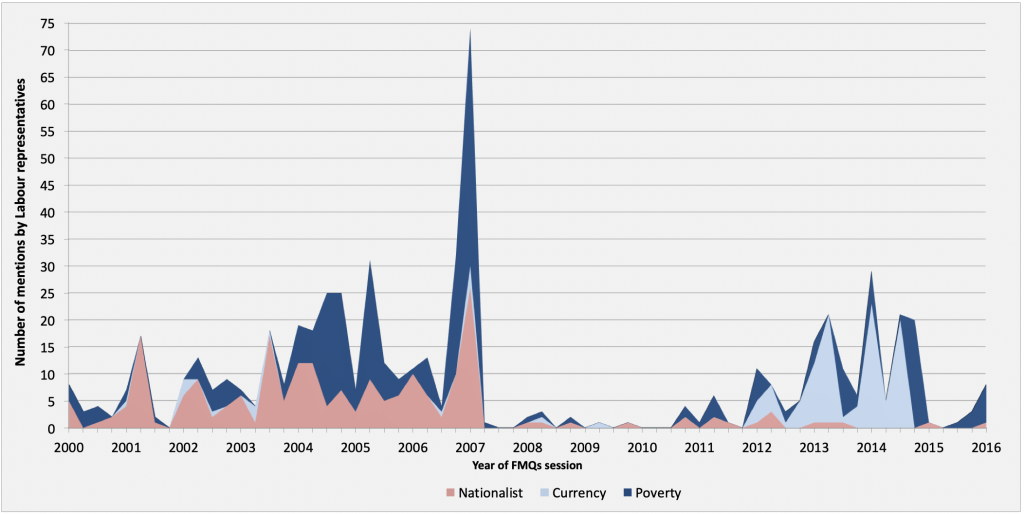

The strategic approaches Labour adopted can be gained by counting the number of times certain key words occur within the written record of contributions to sessions of FMQs by Labour representatives. An important part of Labour’s pre-2007 strategy of questioning the SNP’s progressive credentials was referring to the latter by the ‘nationalist’ label the party looks to distance itself from. This makes a simple count of the number of times the party’s MSPs used that term one way of tracking the extent to which Labour adopted that strategy. Similarly, tracking use of the term ‘poverty’ provides an indication of the extent to which party representatives used language redolent of a left-of-centre stance, as this is a word that is disproportionately used by those on the left of the political spectrum. Meanwhile, use of the word ‘currency’ provides an indicator of the extent to which Labour adopted a strategy of questioning the economic viability of Scottish independence, the issue of what currency a newly independent Scotland would adopt being an important aspect of the economic critique of independence.

The results presented in Figure 1 clearly show Labour MSPs frequently using the terms ‘poverty’ and ‘nationalist’ in the period up to and including 2007, followed by a dramatic decline after the party entered opposition. In 2011, use of the term ‘poverty’ begins to rise again, however there is no accompanying increase in the use of the term ‘nationalist’. Labour appears to have not returned to its pre-2007 strategy of attempting to associate the SNP with a non-progressive ideology. Instead, use of the term currency increases, indicating that the party increasingly employed a strategy of criticising the SNP’s stance on economic grounds.

Figure 1: Number of uses of the terms ‘nationalist’, ‘currency’ and ‘poverty’ by Labour representatives during First Minister’s Questions Sessions in the Scottish Parliament 2000–2016

I argue that this increased focus on the economic case against independence has damaged Scottish Labour’s ability to present itself as a clearly left-of-centre party relative to the SNP. Left-of-centre politicians tend to talk positively about their ability to deliver improvements to public services. Right-of-centre ones, on the other hand, emphasise the financial constraints within which the objective of better public services must be pursued. In focusing on the economic constraints within which an independent Scotland would be forced to operate, Scottish Labour used language more redolent of the right-of-centre ones.

The negativity of the arguments Labour deployed can also be seen as undermining any attempts by the party to portray itself as being at least as pro-Scottish as the SNP. In focusing on the things Scotland would not have as an independent country rather than on what it could have as a part of the UK, Labour allowed the SNP’s case that independence constitutes the more positive, pro-Scottish, and progressive answer to the constitutional question to go relatively unchallenged.

There is evidence to suggest that the type of image Labour and the SNP projected during the period studied had some effect on public perception of the respective parties’ policy identity. Opinion poll data from the British Election Study shows that during the year the independence referendum took place, when Labour’s association with the critique of the idea of independence based on economics would have been particularly prominent, Scottish public opinion shifted from seeing Labour as the most left-wing of the main Scottish parties to viewing the SNP as occupying that position.

The example of the separation of the former Czechoslovakia into its component parts demonstrates the potential effects of a significant number of voters coming to believe that they can only have the economic policies they want via territorial secession. In that example, Slovak voters hostile to free market reforms introduced after the collapse of communism came to feel they could only block those reforms by seceding from Czechoslovakia, and this happened despite their being little evident pre-existing desire for Slovak independence. The fate of Czechoslovakia shows that multi-national states such as the UK can only survive when there is maximum potential for all types of political contestation to take place within the existing constitutional framework. In the Scottish context, this means that the SNP’s strategy of characterising social democratic goals as best attainable through an independent Scotland must not go unchallenged. Scottish Labour’s role must be to provide that challenge. It must be to argue the positive, progressive case for the union.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Parliamentary Affairs.

Kieran Wright is Postdoctoral Research Assistant in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent.

Kieran Wright is Postdoctoral Research Assistant in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent.

Featured image credit: christopherhu on Flickr under a CC BY 2.0 license.