The sharp increase in hate crime that was recorded in the aftermath of the Brexit vote was more pronounced in pro-Remain areas, write Facundo Albornoz, Jake Bradley, and Silvia Sonderegger. They write that this was because the referendum was a source of new information about society’s overall preferences over immigration, enabling those holding anti-immigrant sentiments but living in areas which are generally supportive of diversity to externalise their views.

The sharp increase in hate crime that was recorded in the aftermath of the Brexit vote was more pronounced in pro-Remain areas, write Facundo Albornoz, Jake Bradley, and Silvia Sonderegger. They write that this was because the referendum was a source of new information about society’s overall preferences over immigration, enabling those holding anti-immigrant sentiments but living in areas which are generally supportive of diversity to externalise their views.

In the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, the police reported a significant surge in racially motivated hate crime which immediately grabbed the headlines. Newspapers’ concerns were consistent with the data. Similar to other studies, we document an abrupt spike in hate crime following the vote. But we also uncover a new, intriguing fact: the increment in hate crime was more pronounced in areas that voted Remain, despite these areas having generally lower incidents of hate crime per immigrant. What can explain these facts and their timing?

We argue that the referendum triggered a change in the behaviour towards immigrants and people from ethnic/religious minorities: the rise in hate crime was an extreme expression of a more general shift in behaviour. The advantage of using hate crime is that, precisely because it is against the law, it is documented in crime statistics and is easily measurable. Even if not the only motive, many linked the referendum result to the xenophobic rhetoric of the pro-Brexit campaign. Interestingly, despite the ardent debates about immigration, hate crime trends remained unchanged until just after the referendum result was announced.

In our theoretical model, we argue that the referendum altered the dominant social norm by publicly revealing that anti-immigrant views across the country were more widespread than was previously believed, and this caused the norm to shift, rendering anti-immigrant attitudes more acceptable. Furthermore, the release of new information about pre-existing (but hidden) anti-immigrant sentiment explains why the increment in hate crime was more pronounced in Remain areas. This result relies on what we call the referendum’s ‘surprise effect’, which is consistent with the observation that the leave camp victory was, by and large, unexpected. Using data from the British Election Study, we find that this surprise effect was more pronounced in Remain areas. In turn, this caused the behavioural adjustment (reflected in the increment in hate crime) to be larger in those areas.

Intuitively, an individual hostile to immigrants who nevertheless lives in an area where people are supportive of diversity will conform with a perceived norm that is strongly against expressing anti-immigrant views and will refrain from expressing their xenophobic views. If they then discover that, actually, the country at large shares their views, their behaviour will adjust. And this adjustment will be more noticeable in areas characterised by a strong pro-immigration norm.

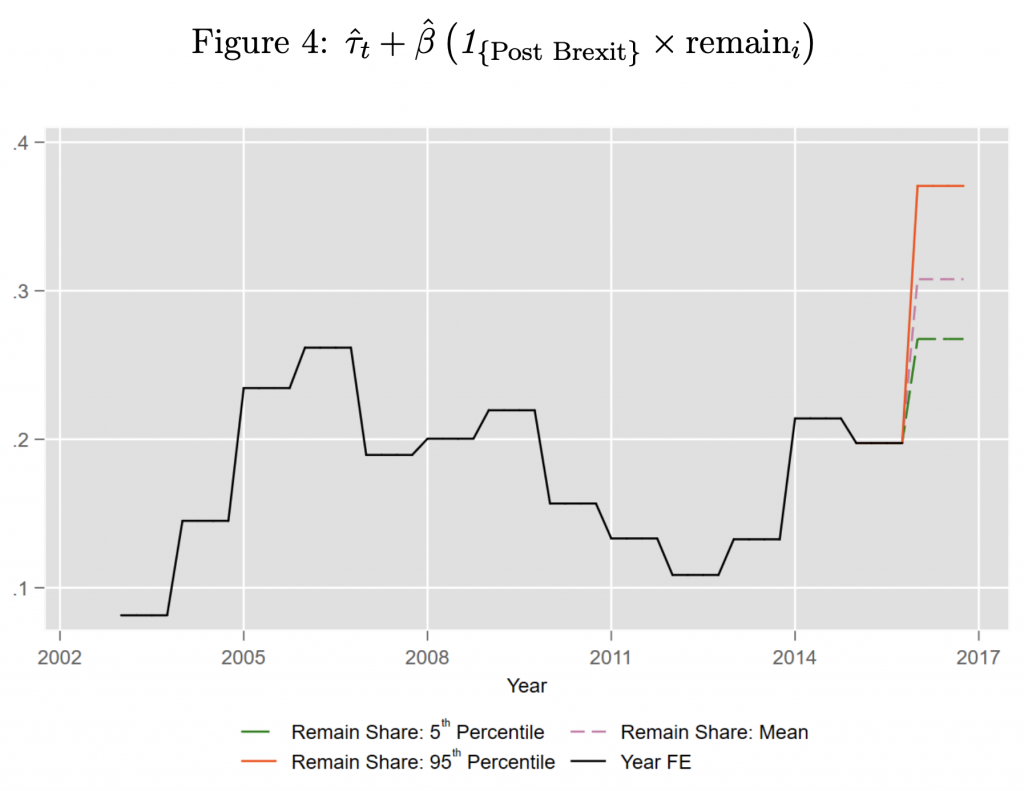

And this is indeed what we find in our empirical analysis. After controlling for the main potential determinants of hate crime (e.g. economic indicators, migration and population flows), we implement a difference-in-difference approach where we estimate the coefficient associated with a dummy indicating post-Brexit financial quarters multiplied by the share of electorate who voted Remain. We find that a one percentage point increase in the proportion voting Remain in each community increases the level of hate crime by half of one percent. To have a visualisation of the effect, we plot this quasi-elasticity for three hypothetical communities representing the fifth, median and ninety fifth percentile according to their share of votes for remain. This way we can show that Brexit resulted in a more than ten per cent increase in hate crime for the average community.

The geographical variation in the change of hate crime would be the opposite of what we observe if the effect was driven by changes in preferences over immigrants. To illustrate the different patterns of norm-driven or preference-driven behavioural changes, we report the geographical distribution of the rise in hate crime triggered by a different event – the London 2005 7/7 terrorist attacks – which fostered an increment in anti-immigrant preferences. The increment in hate crime following the attacks was more pronounced in Leave areas, suggesting that preference shocks (such as that caused by the terrorist attacks and subsequent media frenzy) generate a stronger behavioural response in areas where anti-immigrant sentiment is already widespread. This is the opposite of what we observed in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum and supports our hypothesis that the post-referendum spike in hate crime was a norm-based phenomenon.

Of course, our analysis is based on reported hate crime, which naturally raises the concern that our findings simply reflect changes in reporting. Indeed, we find that there was a potential upswing in reporting rates at the time of the Brexit referendum. However, this effect of the referendum, even if interesting in its own right, vanishes after controlling for police force-year fixed effects, which we include in our regressions on hate crime without any relevant effect on the results.

Finally, we unify the theoretical analysis and empirical evaluation by structurally estimating a version of our model. In order to do this, we make parametric assumptions regarding voting behaviour and how attitudes manifest into hate crime. Estimates suggest that an individual’s propensity to conform to a societal norm determines approximately a quarter of overall behaviour. To our knowledge, this is the first estimation of how conformity affects behaviour beyond the lab. Our estimates confirm that the size of the informational shock generated by the outcome of the Brexit referendum, as measured by the difference between prior and posterior beliefs about underlying views in society, was indeed large. In this respect, the referendum really acted as a ‘bolt from the blue’ that had a real impact of the life of foreigners and ethnic minorities in the UK.

____________________

Facundo Albornoz is Professor of Economics at the University of Nottingham.

Facundo Albornoz is Professor of Economics at the University of Nottingham.

Jake Bradley is Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Nottingham.

Jake Bradley is Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Nottingham.

Silvia Sonderegger is Professor of Economics at the University of Nottingham.

Silvia Sonderegger is Professor of Economics at the University of Nottingham.

Photo by Andre Hunter on Unsplash.

Hate crime rose because of the right wing dominated uk press and TV, especially the pre referendum BBC and Sky press previews . They were not concerned, they wanted a reaction to give them media clips and press headlines. The real fake news came from the UK an

d the