Following the 2017 Budget, Michael Ellington and Costas Milas offer some first comments on why, regardless of whether one supports Britain’s exit from the EU or not, the current situation is not good news.

Following the 2017 Budget, Michael Ellington and Costas Milas offer some first comments on why, regardless of whether one supports Britain’s exit from the EU or not, the current situation is not good news.

To keep Brexiteers off his back, Chancellor Hammond did not spell it out, but Brexit-related uncertainty is taking its toll on the economy: anaemic GDP growth of 1.5% is predicted for the next four years, and will only be lifted to 1.6% three years after Brexit – in 2022. Of course, this will be the case if there will be no further political crises in the interim, like a challenge to Theresa May’s leadership and/or a snap election.

Whether you call yourself a Brexiter or a Remainer, there is nothing to be cheerful about, with GDP forecasts being considerably lower than the 2.1% median recorded over the last 300 years or so. And all of this because we decided to cancel our EU membership, which guaranteed security on our trading business with our European partners and the rest of the world. Instead, we are now consumed with the unproductive and embarrassing talk of an ‘Exit bill’ which we need to agree with our former partners before even contemplating a one-to-one trade deal with the rest of the world. But then Hammond set aside a further £3 billion to prepare for Brexit. Is this supposed to cheer us up when Brexit-related ‘insurance’ preparations keep on rising?

In this context, no wonder UK total investment has got stuck at 17% of our GDP (compared with an EU investment-to-GDP average ratio of 20%). At the same time, UK business investment, at 9.5% of our GDP, lags behind an EU business-to-GDP average ratio of 12.5%.

With investment at these levels currently hitting hard our productivity prospects and wage incomes, UK businesses have desperately been looking for budgetary measures or, at least, some form of government assurance to support their future plans. Having brought the UK’s corporate tax rate down to 19% in 2017, we did not find in the Budget an earlier government commitment to a further corporate tax reduction to 17% in 2020. Did Hammond abandon his plan for 2020? This will probably confuse businesses.

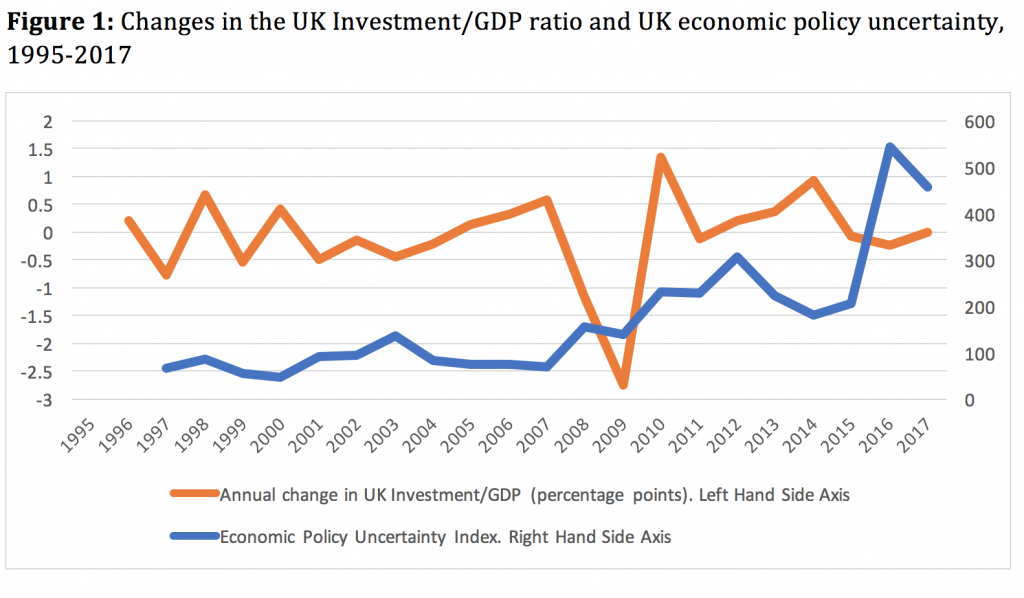

Nevertheless, the UK’s existing corporate tax rate of 19% is already much lower than the 24% average for 34 OECD countries. This might be helpful for existing businesses and may even attract additional ones. But it will not be enough to counteract Brexit-related economic uncertainty which holds back investment (see Figure 1). UK businesses would prefer explicit government assurances – and indeed action – about a smooth divorce today rather than lower taxes in the future.

Note: The policy uncertainty index is constructed based on newspaper articles regarding policy uncertainty from The Times and The Financial Times. It counts the number of newspaper articles containing the terms uncertain or uncertainty, economic or economy, and one or more policy-relevant terms (see here).

Note: The policy uncertainty index is constructed based on newspaper articles regarding policy uncertainty from The Times and The Financial Times. It counts the number of newspaper articles containing the terms uncertain or uncertainty, economic or economy, and one or more policy-relevant terms (see here).

In any case, the Chancellor announced measures to promote maths teaching in schools. Considering how widely the now-discredited claim that Brexit equals £350million additional weekly funding for the NHS was propagated – not least by his colleague, Boris Johnson – this may be some form of consolation offered in this year’s Budget.

_____

About the Authors

Michael Ellington is Lecturer in Finance, University of Liverpool.

Michael Ellington is Lecturer in Finance, University of Liverpool.

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance, University of Liverpool.

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance, University of Liverpool.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Our Economy is private sector driven,it comes as no surprise to me that when living standards are falling that investment goes in the same direction.

People are the real economy not the City of London, when are we going to recognise that and stop taking notice of the pure bunk they preach?