Lee Elliot Major and Stephen Machin explain how Britain has become less mobile, particularly at the top and bottom of society.

Lee Elliot Major and Stephen Machin explain how Britain has become less mobile, particularly at the top and bottom of society.

One David was born in a terraced house in East London, his father a kitchen fitter, his mother a hairdresser. The other David grew up in an idyllic village in the English countryside, his father a stockbroker, his mother the daughter of a baronet. The first David left school at 16 without any qualifications; the second studied at Eton and Oxford. One married an Essex girl; the other married the daughter of a wealthy aristocrat.

Both Davids in their own way highlight Britain’s social mobility problem. David Beckham’s meteoric rise is a rare occurrence: few children born to poor parents climb the income ladder of life. Meanwhile, David Cameron continued a tradition that has seen successive generations of social elites retain their grip on the country’s most powerful jobs: he is descended from King William IV who ruled in the 1830s.

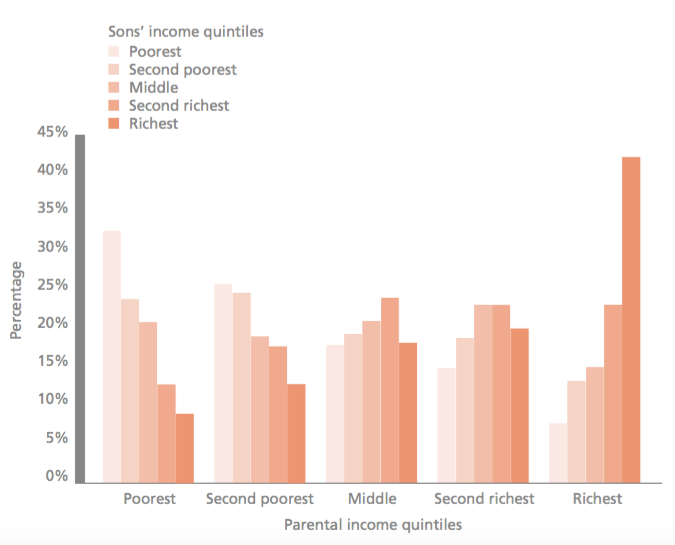

Social mobility tells us how likely we are to climb up (or fall down) the economic or social ladder – and too many of us are destined to end up on the same rungs as our parents. That’s what we conclude in our new book – after reviewing the evidence. The analysis confirms how Britain became less mobile, particularly at the top and bottom of society. A quarter of sons born in 1958 from the poorest homes remained among those on the lowest incomes as adults, while 32% of those born into the richest families stayed among the top earners when they grew up.

Rather than opportunities getting better for more recent cohorts, they have got worse. Around a third of sons from a cohort born 12 years later in 1970 from the poorest background remained among those on the lowest earnings as adults. And over 40% of those born into the richest fifth of society remained there themselves as adults. This strong U-shape of social mobility with people stuck at the top and bottom of the distribution across younger generations is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Intergenerational mobility in the 1970 British Cohort Study

What’s more, today’s younger generations face a bleak future: greater income divides, wider gaps in abilities to enter the housing market, lower relative wages and shrinking opportunities.

Figure 2. The Great Gatsby curve

Source: Jo Blanden (2011) ‘Cross-country Rankings In Intergenerational Mobility: A Comparison of Approaches from Economics and Sociology’, Journal of Economic Surveys 27: 38-73.

The dream of just doing better, let alone climbing the social ladder, has been dying. The well-known ‘Great Gatsby curve’ (pictured in Figure 2) reveals a strong link between countries’ Gini coefficients (which measure income inequality) and their intergenerational earnings elasticities (which measure immobility).

There is mounting evidence to suggest that wide gaps between the rich and poor lead to more rigid societies. And the problem for Britain is that, as in the United States, we have high inequality and low mobility. It does not bode well. By much more than earnings, wealth – financial investments and property – sets the elites (including the two Davids) apart from the rest of us.

Meanwhile, workers’ wages have declined sharply in real terms. In the decade from 2008, median wages fell by 5% in real terms. Employees are now worse off than their equivalents ten years earlier. In contrast, their parents, three decades earlier, were enjoying rising real wages compared with the generation before. Just as their counterparts in the United States have been for some time, our young are now facing falling levels of absolute social mobility.

The ‘enemies’ of social mobility

We all agree that talent and hard work rather than background should determine success in life. Yet the enemies of social mobility are powerful and plentiful: ‘opportunity hoarders’, privileged parents playing or cheating the system to stop their children sliding down the social ladder; exploitative employers failing to invest in their staff; and detached ruling elites, vowing to work for the many, but pursuing policies for the few.

We persistently cling onto the hope that education can act as the great social leveller, enabling children from poorer backgrounds to overcome the circumstances into which they were born. But the evidence shows that on average schools and universities have failed to live up to these lofty expectations. It’s an impossible task when inequality is so wide outside the school gates.

We estimate that hundreds of thousands of young people continue to leave school without the basic numeracy and literacy skills to get on in life. Meanwhile, private school alumni have maintained their stranglehold on our political and professional elites, as well as leading positions in other areas of public life, including the film and TV industry, the arts, music and sport. Low mobility incurs economic, social and political costs. It leads to greater regional divides and to polarised and populist politics. Elites have become regionally concentrated and more detached from, and uninterested in, the rest of society.

Marginalised voters feel left behind and are more likely to vote for extreme parties. Failure to do something will only store up greater problems for the future. Life prospects will be linked not just to the status of your parents, but also to that of your great-great-great- grandparents as multi-generational mobility becomes stickier.

A new model of social mobility

Britain desperately needs a new model of social mobility that develops all talents, not just academic, but vocational and creative – and creates opportunities across the whole country, not just in London. Employers need to treat employees as a long-term investment, and offer training and skill development that can raise productivity. Britain’s booming gig economy has created an employment underclass lacking security, training, progression or rights, stuck on short-term and temporary contracts (or ‘gigs’).

We could also do more to open up access to the top employers and universities. All work experience placements and internships at elite firms, for example, should be paid and openly advertised. Bombarded by thousands of A-grade candidates, sought after universities are resorting to ‘hyper-selectivity’ – ever more refined but unreliable ways of selecting the ‘very best’ academic talent. They could instead identify the minimal grades that are good enough to get in. Undeniably, the most equitable way to allocate places to equally deserving candidates would then be to pick them randomly. ‘Losers’ could be guaranteed a place at another university. Overnight, we could diversify student intakes.

Meanwhile, the government could raise inheritance tax and close the tax loopholes that allow the super-wealthy to entrench their privilege. But such moves require political courage, not empty rhetoric. David Cameron’s advisers came up with a clever phrase for the then prime minister to demonstrate his aspirations for a classless society: ‘It’s where you’re going to, not where you’re from that counts.’ But that mantra was a fallacy. In Britain, it has become increasingly the case that where you come from – whom you are born to and where you are born – matters even more for where you are going to.

____________

Note: the above was originally published on CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) and is based on the authors’ book Social Mobility and Its Enemies, Pelican (2018). Featured image credit: DesignRaphael Ltd, NOT under Creative Commons. All rights reserved.

About the Authors

Lee Elliot Major is chief executive of the Sutton Trust, the UK’s leading foundation improving social mobility through education. He is an adviser to the Office for Fair Access.

Lee Elliot Major is chief executive of the Sutton Trust, the UK’s leading foundation improving social mobility through education. He is an adviser to the Office for Fair Access.

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics at LSE and Director of the School’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). His expertise is in labour market inequality, economics of education and economics of crime.

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics at LSE and Director of the School’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). His expertise is in labour market inequality, economics of education and economics of crime.

Born in 1958

The daughter of a working class English woman and a Jamaican labourer. Originally took the old certificate of secondary education. Encouraged to go to a college of FE inYorkshire took O and A levels. Got to Manchester Unversity in 1978 graduated in 1981 with an honours degree. Post grad qualification in social work and have been working to encourage all children for nearly 30 years. This lack of opportunity in the UK have helped develop the currrent situation in which we find ourselves. We need to do everything we can to ensure a prosperous future for all our children.

Every dog will have their day, in a way. For people who are not religious/spiritual it is a fact that one get to have only one life, and that means very many people are going to be disappointed due to the conditioning given them by our western culture these days. To aspire to advance in your station in life is to risk disappointment. Many are called, few are chosen. The growth curve sinds WWII has n the West been extraordinary for the working class and the broad middle class. Likewise, in the upper middle class wealth has grown and grown. There have been times of such growth before, for all or some of the various classes of free citizens, but probably nothing like this. Will it go on getting better? Not if history is any guide.

Social mobility has been introduced and made into some concept that is below the consciousness horizon of many people. It is the carrot dangling in front of workers. Competition is reckoned to be a necessity for society to function effectively. Stasis might set in and the country taken over by more enterprising people. However, too much competition is as dangerous as, or more so than, too little competition. The trick for government is to know how much competitive behaviour and inventive endeavour is optimal. Unfortunately, few governments are run by people who are wise. Government is power, the people seeking power are not wise per definition. Hence, government is run by the people who are in power for the benefit of they who are in power. As a consequence, the collective effort is divided according to the power different people and classes are able to bring to the table in the temple of political discourse, a lot of which is out of sight of the public at large.

In the West, mobility is higher where inequality is lower.

A major comparative study by the US-based Stanford Centre on Poverty and Inequality found that a father who makes twice as much as another (i.e., 100% more) can expect his son to earn 50 to 60% more in adulthood in countries like Peru. In Australia, the disparity is less than 30%, whereas the US and UK are close to 50%.

Over 50% of lifetime income is decided by just one factor with no connection to “hard work” or “ability”: the country we live in. When combined with the fact over 96% of people live in the country they are born in, citizenship and the lottery of birth are decisive for earning capacity and well-being. United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty Philip Alston pointed out that the US has one of the lowest rates of social mobility between generations of any rich country – not least because child poverty is so prevalent.

So government policies to aggressively ensure social and economic equality really do matter – except to Laberal governments here to promote the wealth and greed of their filthy rich patrons.

So equality matters, good incomes matter, and the damage done to both by “free” trade and globalisation matters.

Very informative article.

Born 1942 – about the best time for the bright but underprivileged. Wartime balanced diet, 1944 Education Act,

recovering economy.

Still reatain some part hidden resentments about the bias in the system.

Position now could turn equivalent resentments into social upheaval or non-co-operation.

Well done for this post on this highly important subject. I think it possible that the situation is worse in the UK even than in the USA because the USA is so big. The people who live in Arkansas do not suffer much from the fact that they earn less on average than those in New Jersey, just as people in the UK are not terribly bothered about earning less than Luxembourgians. If the USA were split into UK-sized chunks, it is possible that the chunks would have better mobility and less inequality than the UK, where you really do have the poorest and the richest living two streets away from each other, and virtually zero chance of moving from the poorer to the richer world.

I think education has a lot to do with it. I have the impression that the majority of the educated elite in the UK were either educated privately or else in the sort of state school that only exists in rich areas. In Germany this is not the case. There are schools where parents pay 100% of the school fees, but they are much much rarer. Not that everything in Germany is perfect of course.

“We estimate that hundreds of thousands of young people continue to leave school without the basic numeracy and literacy skills to get on in life”

It is my opinion that this is more the fault of the parents than the schools. It has always been said that education starts at home but the present generation of young parents are quite incapable of teaching their children anything apart from drink, consuming dangerous substances and copulate. Respect for othersseems to have gone out of the door.to.

I had a turbulent childhood, I lost my mother at the age of 11, shortly after I was admitted to grammar school.and I was a very bad pupil. I left school at 16, with 2 GCEs I think and got a job in a British Railways booking office. I was quickly moved to the regional office. I then moved to London and got a job in a travel agency that account with BP and Marks & Spencer. I got the job of manager of a small travel agency in East London and there I met a Spanish lady who is now my wife. We’ve just celebrated our 46th anniversary.

We opened our own travel agency in east London. By this time I was fluent in French. self taught, free travel with BR had helped. We decided to move to Spain and within a year I was fairly fluent in Spain, no thanks to my wife, we used to argue too much. The trick is to avoid British people, pubs, TV etc.

I wasted my time at grammar school but I did not allow it to prevent me doing what I wanted to do. We’re not rich by any means but we do have a nice villa, five minutes walk from the Med. and paid for, I can see the lights in Morocco at night, we go on 2-3 holidays a year and one of them is usually a cruise. This despite being a lousy school pupil.

My wife spoke Spanish at home and was educated in French. Her family went to the UK when she was 16 and she had to find work without speaking English. She is now trilingual, as I am.

Neither my wife or I can say we are where we are because of the education we got. It wouldn’t be true. We are where we are because we are strong willed and bloody minded.

Many young people nowadays would perhaps do better if the were separated from the deadbeat parents.

I very much appreciate the pertinence and accuracy of this article. It articulates all the things I’ve believed for years, but have been unable to convince my mates at the golf club!

I’m convinced this social inequality has brought about the Brexit debacle, and of course the US Trump shambles. The UK and US versions of Democracy have failed to deliver social and economic strategy which exploit the potential of children from lower income families, and at the other end of the wealth scale have ensured that mediocre minds from richer families retain their stranglehold on higher paid (and more importantly, more influential) jobs. My favourite uncle …. a bright man, but with little education, used to say in the 1950’s, “bullshit baffles brains”. And he didn’t even know anyone who had studied PPE.

Trying to explain Gini’s coefficient to the man on the street continues to be a challenge though.