Is homelessness such a fairly random event that it could happen to anyone, as it is often claimed? Suzanne Fitzpatrick explains why this is not a valid claim, and that repeating it could distract us from focusing on causes that may be identifiable, and possibly preventable.

Is homelessness such a fairly random event that it could happen to anyone, as it is often claimed? Suzanne Fitzpatrick explains why this is not a valid claim, and that repeating it could distract us from focusing on causes that may be identifiable, and possibly preventable.

In a laudable attempt to avoid the ‘othering’ of those suffering acute forms of disadvantage, such as poverty or homelessness, it is sometimes argued by charities and other progressive voices that these misfortunes ‘can happen to anyone’. With respect to homelessness specifically, sympathetic politicians, academics, and others often rehearse mantras such as ‘homelessness results from many different causes’ and ‘homelessness is hugely complex’.

Well-intentioned as they are, such statements can create the impression that homelessness is a fairly random event, its causes largely unfathomable, and attempts at prediction are doomed to fail. But is the risk of homelessness really so widely distributed across the population as to justify the common media refrain that we are ‘all only two (or one, or three) pay cheques away from homelessness’? Or do such ‘inclusive’ narratives distract from deeper structural and other causes that may be identifiable, and possibly also preventable, should the political will be found?

In a paper published in Housing Studies, Glen Bramley and I demolish the ‘two paycheques’ myth via an analysis of three major UK surveys that ask about past experience of homelessness: the Scottish Household Survey; the UK-wide Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey; and the British Cohort Study (focusing on the cohort born in 1970). We demonstrate that poverty, particularly childhood poverty, is by far most powerful predictor of homelessness in young adulthood. Health and support needs, such as serious drug use, also contribute to homelessness risks, but their explanatory power is less than that of poverty. Social support networks are a key protective ‘buffer’, but again the link with homelessness is weaker than that with material poverty. Where you live also matters, with the odds of becoming homeless greatest in higher housing pressure areas, but these additional ‘area’ effects are considerably less important than individual and household-level variables.

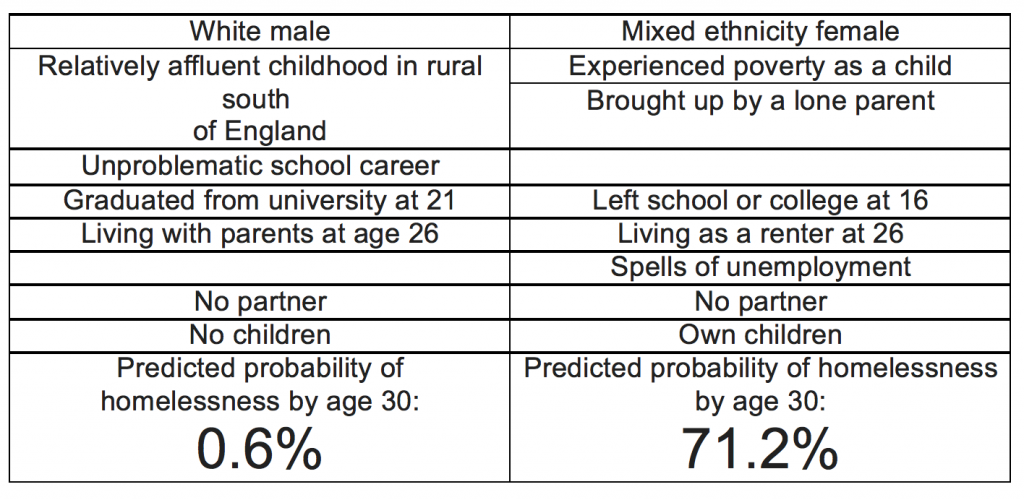

The fact of the matter is that, for some systematically disadvantaged groups, the probability of homelessness is so very high that it comes close to constituting a ‘norm’. Conversely, for other sections of the population, the probability of falling into homelessness is slight in the extreme because they are cushioned by many protective factors. Two vignettes, drawn from either end of this risk spectrum, serve to illustrate the point:

The idea, then, that ‘we are all only two pay cheques away from homelessness’ is a seriously misleading statement. But some may say that the truth (or falsity) of such a statement is beside the point – it helps to get the public on board and aids fundraising. Maybe that’s true (I haven’t seen any evidence either way). But myths like these become dangerous when they are repeated so often that those who ought to, and need to, know better start to believe them. I have lost count of the number of times I have heard senior figures from government and the homelessness sector rehearse the ‘it could happen to any of us’ line. This has to be called out for the nonsense it is, so that we can move on to design the sort of effective, long-term preventative interventions in homelessness that recognise its predictable yet far from inevitable nature.

The idea, then, that ‘we are all only two pay cheques away from homelessness’ is a seriously misleading statement. But some may say that the truth (or falsity) of such a statement is beside the point – it helps to get the public on board and aids fundraising. Maybe that’s true (I haven’t seen any evidence either way). But myths like these become dangerous when they are repeated so often that those who ought to, and need to, know better start to believe them. I have lost count of the number of times I have heard senior figures from government and the homelessness sector rehearse the ‘it could happen to any of us’ line. This has to be called out for the nonsense it is, so that we can move on to design the sort of effective, long-term preventative interventions in homelessness that recognise its predictable yet far from inevitable nature.

On a slightly different note, the repetition of this falsehood seems to me to signal a profoundly depressing state of affairs i.e. that that we feel the need to endorse the morally dubious stance that something ‘bad’ like homelessness only matters if it could happen to you. Are we really ready to concede that social justice, or even simple compassion, no longer has any purchase in the public conscience? Moreover, it strikes me as a very odd corner for those of a progressive bent to deny the existence of structural inequalities, which is exactly what the ‘two paycheques’ argument does.

So let’s leave it behind. Let’s be honest that homelessness probably won’t happen to you (if you are middle class). But you should care about it anyway. Because it’s happening to an increasing number of your fellow citizens. And it’s miserable, unfair, and preventable in the world’s sixth biggest economy.

______

Note: this article draws on the author’s co-authored paper, published in Housing Studies (DOI:10.1080/02673037). The article is currently open access.

Suzanne Fitzpatrick is Professor of Housing and Social Policy in the Institute for Social Policy, Housing, Environment and Real Estate (I-SPHERE) at Heriot-Watt University.

Suzanne Fitzpatrick is Professor of Housing and Social Policy in the Institute for Social Policy, Housing, Environment and Real Estate (I-SPHERE) at Heriot-Watt University.

I’m going to go out on a limb here and assume you’ve never been homeless?

Yes, it CAN happen to anyone. A tornado can come rip your house down and you can get sick and end up in the hospital and lose your job. Your family can be killed in an instant. No one and I mean no one is in control of the forces of nature.

I would say that a white male/female, from single family, with some of traits of left side of you homeless table would be quite high on the list of homelessness or/and ‘potential homelessness’ which is not often talked about. Potential homelessness when a person has no proper home, sofa surfing, inadequate tenancy etc. is highly vulnerable but misses the homelessness radar. Lot of homelessness is from divorce and relationship splits. Majority of people in UK can say they have experienced one of the things on the left side of table so the binary look of the table is deceptive. It isn’t cut and dry. Interesting all the same. The Tory emphasis on Family values and Hostile environment policies has not helped.

While I am certain the author’s analysis of the data was carefully done I think they misunderstand the claim “it can happen to anyone”.

In order to refute it they would need to take the population of homeless that (however unlikely) did, in fact, come from a middle class background and answer at least two questions about them:

1) What percentage of the homeless can be identified as less likely to have become so but fit into th category that the “it can happen to anyone” claim is aimed at. It is clearly not used to communicate with people who have the experience of homelessness of friends and family as a likely event.

2) Of this group, how many found themselves homeless unexpectedly. That is, actually investigate the two paycheck claim not in terms of likelyhood of being any member of the homeless population but in being an unexpected member. Because that is the intent of the communication and it is not tested here.

Considering the known facts that disabled people are being particularly discriminated against re private renting; that accessible housing is not being built for them – us; that they are disproportionately adversely affected by the bedroom tax; that they have been victims of grave and systematic violations of human rights according to the UN; that they have been particularly targeted by austerity policies, despite the fact their cost of living is higher through no fault of their – our – own: why on earth have disabled people been left out of the analysis, the narrative, the equation? Are we really expected to believe our chance of becoming homeless is equal to – as low as – that of a well paid white man?

I have to disagree with this article because I do believe that it can happen to anyone. I see it happening everyday, with the loss of jobs, the high cost of rents, the high cost of utilities, death of a spouse, health issues. substance abuse, mental illness. People are losing their homes and having to live with family, to me that is being homeless. Young kids can not find jobs and are couch surfing at friends houses. You may not see people living on the street in the town or city you live in but trust me there are homeless there. Being homeless can happen to anyone and does everyday.

Oh, really? I have known people from all walks of life who have ended up homeless. Even an ex Eton pupil. Many armed forces personell, air line pilot, international polo player, various levels are vulnerable. It’s not all about money or

education but circumstances getting out of control.

Excellent analysis. It’s about time somebody put the record straight. I particularly endorse the penultimate para although I wonder if the ‘it could happen to anyone approach’ by charities and some politicians isn’t counterproductive since most of us believe we have enough control over our lives to prevent homelessness so we might be forgiven for thinking why can’t everyone else?