The 41st Canadian general election on May 2nd resulted in catastrophic blows to the centre-left Liberal Party of Canada and saw the almost complete demise of the sovereigntist Bloc Quebecois. In their place rose the far right-leaning Conservative party in majority standing and the far left-leaning New Democratic Party as the Government’s official opposition. Anne White considers how this unprecedented change at the Federal level occurred and what it might mean for hung parliaments.

The 41st Canadian general election on May 2nd resulted in catastrophic blows to the centre-left Liberal Party of Canada and saw the almost complete demise of the sovereigntist Bloc Quebecois. In their place rose the far right-leaning Conservative party in majority standing and the far left-leaning New Democratic Party as the Government’s official opposition. Anne White considers how this unprecedented change at the Federal level occurred and what it might mean for hung parliaments.

Monday’s historic Canadian election delivered two strong victories – a strong majority to Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative Government and a first-time official opposition opportunity for the left-leaning New Democratic Party (NPD). It also saw devastating blows to the “natural governing” Liberal Party of Canada and Quebec’s sovereigntist Bloc Quebecois.

The Conservatives captured 167 seats, up from 143 seats whilst the NDP soared from 37 seats to a historic 102 and official opposition status. The Liberals fell 43 seats from 77 to 34 with leader Michael Ignatieff losing his seat. The Bloc Quebecois, a stronghold of Quebec politics since its inception in 1991 was virtually obliterated losing 45 seats including that of leader Gilles Duceppe. Both leaders have since officially resigned their leadership of their respective parties.

Figure 1: Official election results, 41st Canadian General Election

| 2011 Votes (%) | Seats | 2011 Seats (%) | |

| Bloc Quebecois | 6.1% | 4 | 1.3% |

| Conservative Party of Canada | 39.6% | 167 | 54.2% |

| Liberal | 18.9% | 34 | 11.0% |

| New Democratic Party | 30.6% | 102 | 33.1% |

| Other | 4.8% | 1 | 0.3% |

| Total | 100.0% | 308 | 100.0% |

So what happened? Consistent Tory gains in English Canada, a stable NDP surge in Quebec and a long-standing decline of the Liberals.

Though key races in competitive ridings in Toronto kept the electorate guessing about minority vs. majority government until the 11th hour, the polls leading up to the election successfully predicted the general wave of change.

A stable foundation

This is not entirely surprising. For the NDP, there was stability in their surge throughout Canada. Whilst some pundits aimed to draw comparisons between the surge of support for the NDP with the Liberal Democrats in the UK, a closer look at the polls indicate that NDP voters were much less volatile than the Liberal Democrats were. Committed voters were at approx 71% and the voter retention rate of the NDP was also high at about 77% compared to a far less committed Lib-Dem constituency in the UK. Jack Layton, as Nick Clegg was, is also personally popular – easily winning the “Beer Polls” over the past few years, but he has also been seen as “Best Suited for PM” and the NDP as the best party to deal with health care and the environment. By contrast, the Liberal Democrats as a party were not seen as real option for a governing option in the UK and were behind on all major policy positions.

The Quebec factor:

Quebec’s complete turn to the NDP and the complete decimation of the Bloc Quebecois though, was more shocking than anyone predicted. In retrospect, all of the ingredients were there: the Bloc’s struggle to define its raison-d’être in an era of declining sovereignty support, the dismal state of the Liberal party generally and most acutely in Quebec, a social democrat with strong public empathy for Quebecois concerns about culture and language. But the extent of the NDP surge in Quebec was unforeseen – perhaps unexpected.

On the one hand, it is tempting to cheer this result as rejection of the sovereigntist movement and a victory for Canadian federalism. However early indications show this is not necessarily the case. Prominent sovereigntist thinker Jean-François Lisée explains that Quebec’s stale provincial political situation in recent years emphasized a desire for change in the province. The NDP presented the least grave option in making that happen: left-leaning, unable to command a majority and provided a desirably opportunity to rebut the Liberals for past injustices perceived to have been committed against the province – a “win-win” situation as it were.

It is not clear, however, that the idea of the Bloc’s complete demise was considered. Last night, Chantal Hebert, a prominent Quebec political commentator, emphasized this point and the disbelief and regret she expects may pervade the province in the aftermath of the election: “Quebecers are going to wake up tomorrow morning and realise that in trying to defeat Stephen Harper they ended up killing the Bloc.” Indeed, discussions with family and friends in my native Quebec – and countless (scientifically insignificant) Facebook status updates – indicate this may very well be the case.

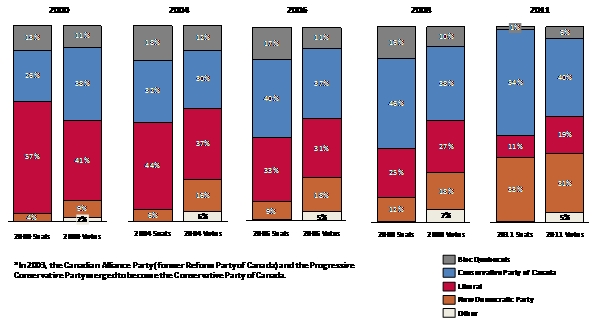

Gain at expense of failure

For the Conservatives, a look at recent federal election results show the party making important incremental gains across the country in the past 4 elections since Stephen Harper took the helm of the merged Conservative Party of Canada. (Figure 2). The gains are largely at the expense of The Liberal Party of Canada – the historically successful centre-left governing option in Canada. One might say there have been two surges on display in Canada’s election – the far-left in Quebec and the far-right in the rest of Canada. Indeed, even if the left had consolidated its vote, (in the imaginary scenario of one merged left-of-centre party) it appears the Conservatives would have remained well in majority range.

Figure 2: Election results of past Canadian Federal Elections

It is not clear that Canadians are particularly comfortable with the brand of Conservatism they’ve just elected. The Prime Minister has already had to reassure the population that he will not make any “radical shifts” in his governing style even though he has full majority control. But the Liberals, having failed to successfully reinvent themselves since their demise as a result of the 2003 Sponsorship Scandal, continue to offer no alternative appealing option. Indeed, the party has gone through 3 different leaders since 2003 and this week’s amazing defeat might indicate the party itself has finally lost all credibility with the electorate. Ed Miliband, take heed.

Reassertion of the traditional ‘Westminster model’?

Comparing the Canadian election with those in other Westminster style parliaments in recent years suggests a conflicting paradigm. On the one hand, trends indicate an increase in political pluralism which has lead to toward hung parliaments, coalitions and, in many cases, a move toward proportional representation (thus solidifying cooperative government arrangements). Professor Patrick Dunleavy in his article on this blog on hung parliaments considers whether these developments may point toward the death of the traditional Westminster model.

On the other hand, Canada has clearly rebuked the trend with this election. In fact, closer inspection of the working arrangements in New Zealand and the UK suggest the electorate may be yearning for a return to more stable majoritarian governance arrangements.

In the UK, the far more left-leaning Liberal Democrats rise to fame appears to have been quite short lived. Indeed, this week’s AV referendum is largely seen as a referendum on the Liberal Democratic Party and Clegg himself. All signs point to a devastating defeat for both party and leader with a resounding “No” result being predicted on the AV referendum and thus, for greater proportional representation in years to come.

In New Zealand, the right-leaning National party is currently polling at majority levels despite a well established proportional representation electoral system which virtually ensures coalitions or minority governments. The underlying causes seem to indicate an electorate exhausted by infighting within the current coalition governing arrangement.

Canadians too had grown weary of what was seen as an uncooperative parliament and polls showed growing impatience with minority administrations by a majority of voters and a longing to return to stable majority government. The Harper campaign even used this fatigue as a campaign strategy – promising a Conservative win was the only way to get a “strong, stable, majority government.”

With increasing pressures of aging societies, heightened expectations for public sector service delivery and complex energy and environmental concerns; it is perhaps unsurprising that voters grow weary of the political infighting and time-consuming compromises which are necessarily a part of cooperative governance arrangements. Indeed, the policy outputs themselves may leave few satisfied even when compromise is reached.

On the other hand, hung parliaments are now the norm in most democracies and the long-term trends in overall vote share for traditional parties are on the decline. Whether these trends hold true for advanced Westminster Parliamentary democracies in the long-term remains to be seen. The upcoming New Zealand election and the evolution of the UK Coalition arrangement post May 5th should provide an opportunity to further test the hypothesis. Until then, in Canada at least, there is strong evidence that the traditional model remains, indeed “traditional.”

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Very intelligently said Anne. 😉

Great Stuff lots of hard work good to see your face love your hair. xo xo Heather.