With a few weeks of campaigning under their belts, and the manifestos released, we might expect to see shifts in appraisals of party leaders and policy positions. But is such movement just a result of voters bringing their assessments into line with their party support as election day looms? In his third blog of the campaign, Joe Greenwood considers this by looking at shifts in appraisals amongst party supporters and the two Brexit camps.

With a few weeks of campaigning under their belts, and the manifestos released, we might expect to see shifts in appraisals of party leaders and policy positions. But is such movement just a result of voters bringing their assessments into line with their party support as election day looms? In his third blog of the campaign, Joe Greenwood considers this by looking at shifts in appraisals amongst party supporters and the two Brexit camps.

Polling following last week’s ITV general election debate showed an unsurprising result: despite being asked to put aside their party preferences, 2017 Conservative voters rated Boris Johnson’s performance more positively, whereas 2017 Labour voters rated Jeremy Corbyn’s performance to have been better. This may be a good example of motivated reasoning, in which people bring their evaluation of one thing into line with their evaluation of a related thing. So, the logic goes, voters prefer a party and this shapes their appraisal of its leader and policy positions. Indeed, this tendency even extends to Humphrey, the 10 Downing Street cat. Conservative voters approve of him more strongly if he is described as Margaret Thatcher’s cat, and less so if he is described as Tony Blair’s cat, with the tendency reversed amongst Labour voters.

There is another possible explanation for this tendency: party support and assessment of policy positions may both be influenced by ideological disposition. As the most prominent representative of the party closest to their ideological views, and a key voice promoting policies that they agree with, we expect voters to like the relevant party leader as well. However, this leads us with a conundrum; do elections force voters to pick a party (often one they have voted for before) and then adjust their views of its policies and leader, or do they allow leaders to pitch policies to the electorate and convince them to support parties? This may be a particularly meaningful question for Jo Swinson, who has seen the Liberal Democrats’ strong polling numbers begin to decline, at the same time as her personal ratings have moved downwards. Is this voters deciding that, when push comes to shove, they cannot support the Liberal Democrats and then bringing their appraisal of the party’s leader into line? Or is it voters being unimpressed by the leader and policy platform, and shifting their vote?

To shed some light on this, we can compare change in the assessments of party leaders from when the general election was called to the weekend of 16-17 November. Specifically, we should focus on the change amongst supporters of each party, whom we expect to be most favourable towards their preferred party’s leader. We can also compare changes in assessments of the best party in relation to Brexit, the NHS, and the economy. Given that Brexit identity is stronger than party identity, we should also look at changes amongst Leavers and Remainers, which are also more stable groups than party supporters. These results are all based on Deltapoll’s numbers to ensure a consistent methodology, and because they ask the relevant questions in each of their polls. It is worth noting that Deltapoll’s figures show the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats remaining largely static (i.e. within the 3% margin of error) during this period, though these small changes in support still affect the make-up of the sub-groups of party supporters who we look at below.

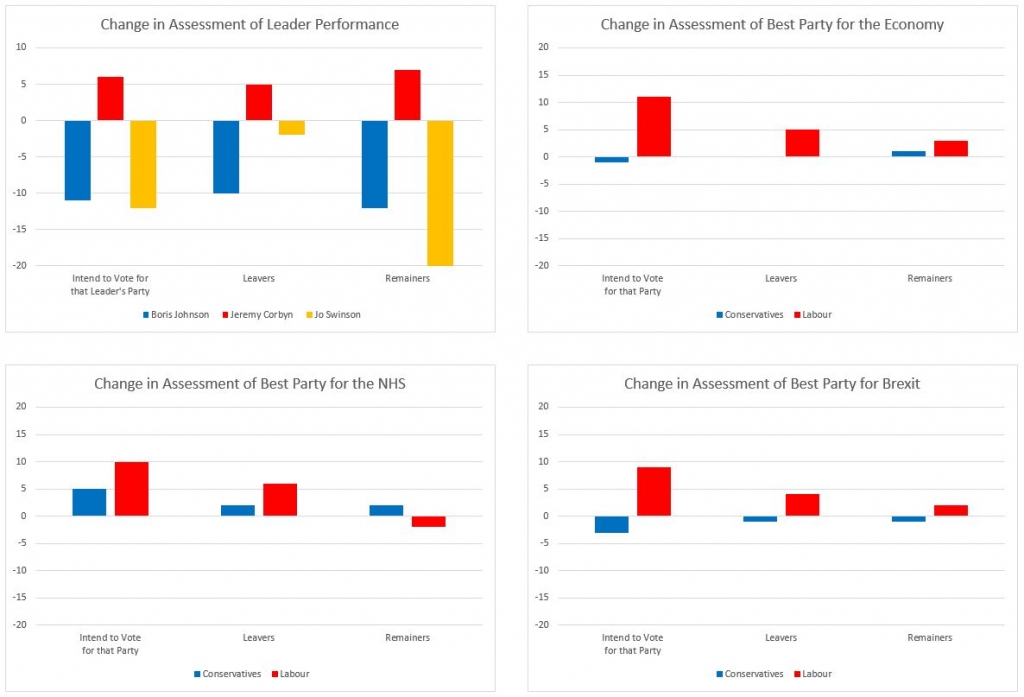

Net appraisal of a leader’s performance is calculated by deducting the percentage who think they are doing badly from the percentage who think they are doing well. Looking at the top left panel of the above figure, we can see the change in net appraisals of the leaders’ performances since the election was called.

As expected, Boris Johnson started with a very positive appraisal of his performance amongst those intending to vote Conservative and amongst Leavers. Those groups’ assessments of his performance have declined (changes of -11% and -10% respectively), though they remain firmly in positive territory (+64% and +39% respectively). Remainers started the campaign with a negative appraisal of his performance, and have adjusted it down further (by -12% to -52%). Most worrying for Johnson is the fall in ratings amongst those planning to vote Conservative, whom we would expect to maintain their positive appraisals.

The appraisals of Jeremy Corbyn amongst those intending to vote Labour is positive and started in positive territory (+6% to +48%) but improvement in ratings amongst Leavers (+5%) and Remainers (+7%) still leave him in negative territory amongst those groups (-66% and -12% respectively).

Appraisals of Jo Swinson’s performance has declined amongst those intending to vote for the Liberal Democrats (-10% to +41%) and Remainers (-20% to -1%). Again, the decline in appraisals amongst her party supporters is most worrying for Swinson, whilst the latter figure is also concerning and could indicate two things. It suggests that Remainers who support other parties (or are contemplating it) have adjusted their appraisal, or that her performance really is not appealing to a key target group.

We now turn to three key policy areas: Brexit, the NHS, and the economy. When asked whether a Conservative or Labour government would be better for the first of those, there is no meaningful change in those who choose the Conservatives. This is probably because it was already high amongst supporters of the party and Leavers, and low amongst Remainers, indicating previous realignments over the issue. Labour does appear to have picked up support amongst those intending to vote for the party (+9% to +77%), either from existing supporters reappraising their position or from those who have switched to the party, indicating that their Brexit line is cutting through with some voters.

Because we are dealing with sub-groups of voters rather than the full sample, the changes in views of which party would be better for the NHS are largely within the margin of error so we are not confident that they have changed meaningfully. There is one exception: notably more (+10% to +85%) of those intending to vote Labour now say that the party would be better than the Conservatives for the NHS.

Finally, on the economy, the only change outside the margin of error is the growing percentage of Labour supporters who think it would be the best party in this area (+11% to +79%). Again, this could be those who have switched to Labour bringing a positive view or existing supporters adjusting their view. Crucially, it should be pointed out that appraisals of the Conservatives by those intending to vote for them remain stronger in all three areas (+93% for Brexit, +90% for the NHS, and +91% for the economy) than the equivalent figures for Labour amongst their supporters.

The overarching picture here looks positive for Labour as appraisals of Jeremy Corbyn have improved amongst party supporters and Remainers, whilst Boris Johnson’s ratings are down across the board. However, they started from very different positions, so Boris Johnson is still seen more positively amongst his party supporters and Leavers and, despite having a stronger rating than his rival, Jeremy Corbyn still has a negative rating amongst Remainers. Indeed, there is now a distinct lack of enthusiasm for any of the leaders considered here amongst that group. This is concerning for Jo Swinson, who has seen her rating amongst Remainers and her own party supporters fall markedly.

In terms of policy, Labour supporters are now more positive about the party’s ability to deal with Brexit, the NHS, and the economy. This is all certainly indicative of a gradual shift back towards Labour as the party’s campaign cuts through or voters with reservations (including, perhaps, many Remainers) stump for the party and adjust their appraisals accordingly. Discerning individual-level shifts in these appraisals will have to wait until after the election, when the British Election Study will release their excellent data. That will help to reveal how much voters are bringing their views of leaders and policies into line with the imperative that they choose a party to vote for.

__________________

Joe Greenwood is a LSE Fellow in the LSE Department of Government, where he teaches on GV101 (Introduction to Political Science). He previously worked at YouGov and, before that, completed his PhD at the University of Essex. His research focuses on political participation, privilege, and perceptions in the British context. He tweets @niceonecombo.

Joe Greenwood is a LSE Fellow in the LSE Department of Government, where he teaches on GV101 (Introduction to Political Science). He previously worked at YouGov and, before that, completed his PhD at the University of Essex. His research focuses on political participation, privilege, and perceptions in the British context. He tweets @niceonecombo.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.