Can citizens forecast the outcome of the UK election? In this post, Andreas Murr presents the results of his forecasting model, which predicts constituency level results by asking citizens in each constituency which party they think is likely to win in their area. The forecast suggests that there will be a hung parliament, with the Conservatives as the largest party.

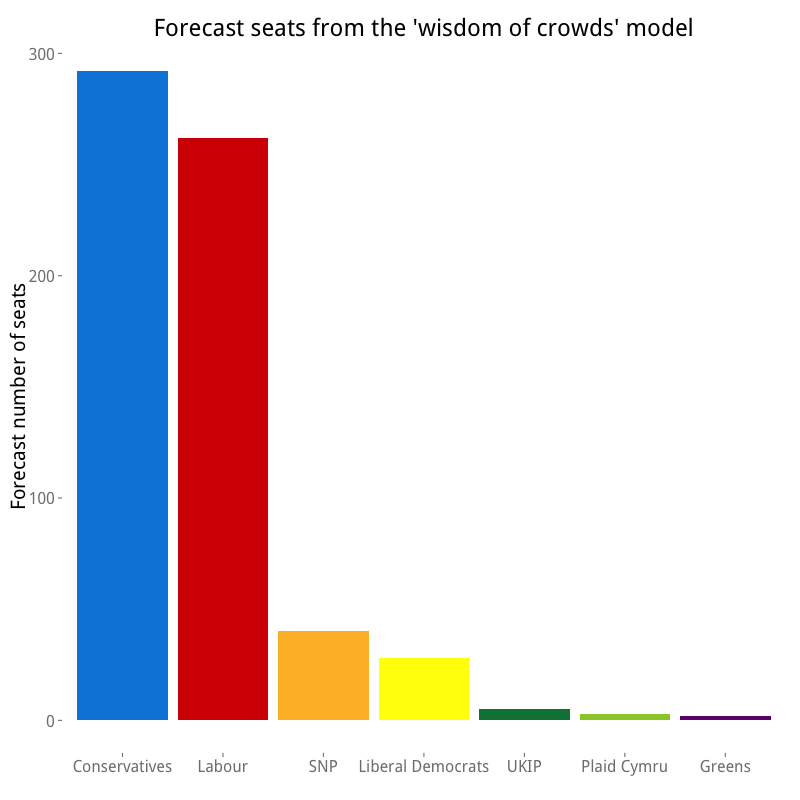

Citizens forecast a hung parliament with the Conservatives as the largest party – about 30 seats ahead of Labour. Citizens forecast also that the Liberal Democrats will win fewer seats than the Scottish Nationals. Citizens made these forecasts in a large-scale YouGov survey that I commissioned using a grant from the John Fell OUP Research Fund. In February and March, the survey asked about 17,000 citizens across all 632 mainland constituencies who they think will win in their constituency in May 2015.

Surveys asking citizens who they think will win are among the most accurate methods for forecasting US presidential elections (Graefe 2014). The so-called “citizen forecasts” are more accurate than expert judgement, vote intention polls, prediction markets, and structural models in predicting who wins and by how much. Why is that?

Citizen forecasts are so accurate because of the “wisdom of crowds”. Condorcet, a French philosopher, showed when it’s wise to go with the forecast of most citizens. If every citizen correctly forecasts with the same, larger than 50 per cent probability, then the probability that most citizens correctly forecast nears 100 per cent as the number of citizens increases. The “wisdom of crowds” emerges even in small groups: for instance, if every citizen correctly forecasts with 60 percent probability, then a group of 25 citizens correctly forecasts with 85 percent probability. The so-called Condorcet’s jury theorem has been generalised in several ways—for instance, to more than two options (List and Goodin 2001). All of these generalisations make it useful for explaining the accuracy of citizen forecasting. So how accurate were citizens at forecasting previous British General Elections?

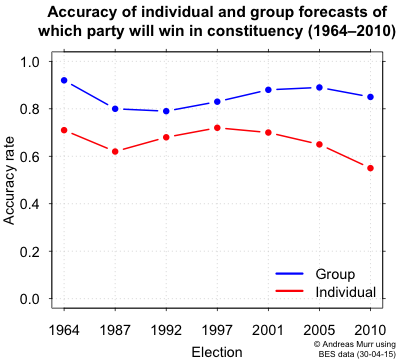

In the past, citizens have accurately forecasted most constituencies and all Prime Ministership in Britain. I found survey data for seven British General Elections between 1964 and 2010 to test the accuracy of citizen forecasts. In all of them, the surveys of the British Election Study asked citizens before or during the campaign who they think will win in their constituency. I then predicted the constituency to be won by the party who most citizens said will win. Across all elections, this prediction rule correctly forecasted 85 per cent of constituencies. Figure 1 shows that in every election, individuals were better than chance in predicting who would win in their constituency, and that groups were even better.

Citizens correctly forecasted most constituencies; they also correctly forecasted all Prime Ministerships. Again, I predicted the constituency to be won by the party who most citizens said will win. I then counted for each party the number of constituencies that it was predicted to win. And then I predicted the Prime Ministership to be won by the party who was predicted to win most constituencies. This prediction rule correctly forecasted electoral stability—such as the Tory re-election in 1992; it also correctly forecasted electoral change—such as the change from Tory to Labour government in 1997. Across all elections, it correctly forecasted all seven Prime Ministers.

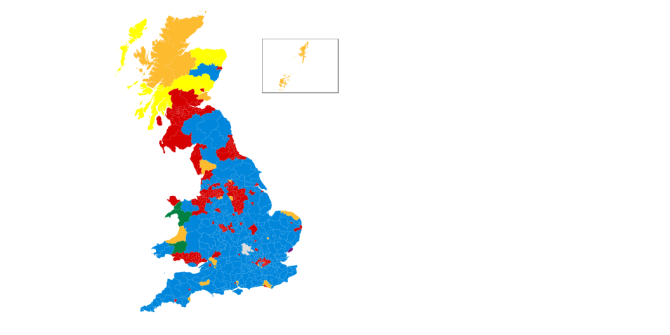

For the current election, I use the same prediction rules as above: I predict the constituency to be won by the party who most citizens say will win it, I count for each party the number of constituencies that it is predicted to win, and then I predict the Prime Ministership to be won by the party who is predicted to win most constituencies. The graph below shows the forecasted number of constituencies that each party will win. As the figure demonstrates, citizens forecast that the Conservatives will become the largest party with 292 seats, followed by Labour with 262 seats, the Scottish National Party with 40 seats, and the Liberal Democrats with 28 seats. These forecasts imply that it is very likely that no party will receive an absolute majority, that the Conservatives will win the Prime Ministership, and that they will need one or more coalition partners to govern.

In sum, citizen forecasts are direct and accurate and comprehensible. Pollsters and political scientists should collect them and communicate their results before every election occurs. If the goal is to forecast who wins and by how much, citizen forecasts provide a simple and successful way to do so.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the General Election blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Andreas Murr is Lecturer in Quantitative Methods in Political Science at the Department of Politics and International Relations. His research focuses on quantitative methods and election forecasting. In one recent article he shows that “delegating and weighting” citizen forecasts by competence increases forecasting accuracy; in another he uses party leadership elections as a form of citizen forecasting to predict who becomes Prime Minister.

Andreas Murr is Lecturer in Quantitative Methods in Political Science at the Department of Politics and International Relations. His research focuses on quantitative methods and election forecasting. In one recent article he shows that “delegating and weighting” citizen forecasts by competence increases forecasting accuracy; in another he uses party leadership elections as a form of citizen forecasting to predict who becomes Prime Minister.

Not so much wisdom of the crowds in predicting outcomes, eh? A better explanation of their views is media echoes.

Why not? In contrast to many, citizens correctly forecasted that David Cameron would be re-elected more than two months before the election. And their seat forecast was more accurate than nine other election forecasting models presented at the LSE in March (). Only Steve Fisher’s forecast was more accurate. Sounds like “wisdom of crowds” to me.