The recent announcement by the Deputy Prime Minister that the Liberal Democrats will not support the redrawing of constituency boundaries because of the failure of Lords reform was a significant break in the course of the coalition. Matt Cole ponders where this may now lead.

The recent announcement by the Deputy Prime Minister that the Liberal Democrats will not support the redrawing of constituency boundaries because of the failure of Lords reform was a significant break in the course of the coalition. Matt Cole ponders where this may now lead.

It has been Nick Clegg’s unenviable but unavoidable role to insist over the last two years that the coalition between his Liberal Democrats and the Conservative Party is a five-year, solid arrangement intended to give stability to the political system at a time of economic challenge. Whilst members of his own party grew frustrated with the trebling of tuition fees, the failures of the referendum on electoral reform and of economic recovery, they – like the Emperor’s loyal subjects in Hans Christian Andersen’s tale – relented from suggesting that the coalition agreement itself does not work. They could criticise the cut of the Emperor’s new clothes; they could question their expense; but to say that they was not there at all was treacherous.

Yesterday, however, Clegg himself stated in bold terms that the rules have changed. In a speech marked by reproachful references to the Conservatives’ “failure to honour the coalition agreement” and to their having “broken the contract” by blocking reform of the Lords, he announced that the Liberal Democrats no longer feel bound by the full coalition agreement. The Deputy PM was frank and detailed in his account of the negotiations (including his offer to put Lords reform to a referendum and delay its implementation) and the Conservative Leader’s intransigence. Significantly, Clegg did not distinguish between the Conservative leadership and the 91 backbench Tory MPs whose rebellion sparked the crisis – Clegg blamed the Conservatives collectively. The Liberal Democrat closest to the Conservative leadership – organisationally and, some would say, ideologically – did not say that Emperor has no clothes, but he at least agreed that there is an embarrassing hole in the material that can’t be patched up. So how will it start to unravel?

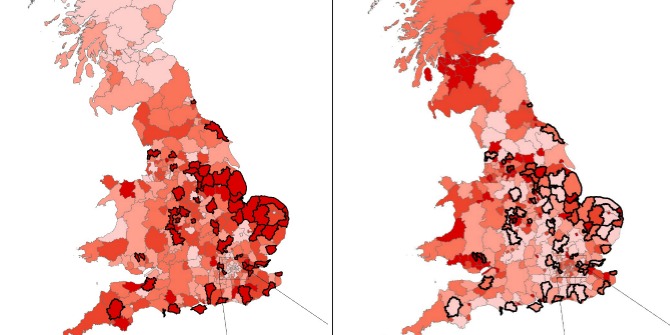

The Liberal Democrats now refuse to support the redrawing of constituency boundaries to reduce the number of MPs from 650 to 600 by the next election. Clegg claims that this is a legitimate response because the introduction of elected Lords was the corollary of the reduction in representation caused by the Commons changes. Critics point out that this is a convenient conclusion since, on a model developed by Lewis Baston (The Guardian 6 June 2011), the Liberal Democrats looked likely to lose 14 MPs – one in four of the current group – as a result of the redrawing, where the Conservatives would have lost 15, less than one in twenty of their current number. Liberal Democrats such as Lord Chris Rennard have in turn pointed to a hidden agenda amongst the Tory rebels over the Lords, many of whom have reason to expect elevation to the Upper House if it remains appointed (Guardian, 3 Aug).

Many of Clegg’s party colleagues will feel liberated from the straightjacket of the full coalition agreement, and will speak and vote more readily against the Conservatives. If they block the boundary revisions, many will feel less anxious about the next election than otherwise. Rennard spoke this morning on Radio Four about the coalition entering a “more mature” phase, and Clegg used the opportunity of his speech to distance the Lib Dems from both the Conservatives and Labour (whose MPs voted down the timetable for introducing Lords reform but not the reform itself). 62% of Lib Dems polled by LibDemVoice.org supported Clegg’s announcement, a further 12% wanted to pull out of coalition altogether, and even Lib Dems admired by the Conservatives such as David Laws were openly calling for the announcement that Clegg has now made in the days beforehand. There is a real possibility that the coalition will drift into a ‘confidence and supply’ arrangement without the Liberal Democrats leaving office, a situation which will infuriate Conservatives and test collective responsibility hard. In these circumstances, Clegg needs to take the initiative to maintain discipline amongst his MPs.

The Conservative Right feel vindicated and have asserted their right to recognition with Cameron, whose position, like that of the Emperor, is now exposed. They are unlikely to let their Leader offer a belated olive branch to the Liberal Democrats (as Clegg urged somewhat forlornly by referring to the hiatus created by the Parliamentary recess) to revive Lords reform. The rebels’ campaign for repatriation of powers from the EU may take on new purpose; and they may become ever more resentful of Liberal Democrat ministers who vote against legislation introduced by their Conservative Cabinet colleagues. However, if the boundary revisions are blocked, the price of preserving the Lords may be defeat at the next election: even on their 2010 vote and under the Baston model, the Tories would have been eight seats short of a majority; with a lower vote and under the current boundaries outright victory is all but inconceivable.

The Labour Party has perhaps the biggest dilemma: its MPs supported Lords reform in principle but blocked its implementation, and its front benchers carped at the detail of the proposals. They must now decide whether to join the Lib Dems in stopping the boundary revisions: to do so would protect Labour’s representation and inflict a significant Parliamentary defeat on the Conservatives; but it would give public endorsement to the Liberal Democrats’ strategy and perhaps even revive their fortunes. There are some in the Labour leadership – including Ed Miliband – who have been careful to cultivate Liberal Democrat co-operation whilst criticising Clegg; there are others, however, who are sworn opponents of any partnership with the third party and the new situation drives a wedge between these two groups.

The forthcoming Corby by-election campaign will be a testing ground for these questions. The tone struck by each party’s candidate, as well as the result achieved, will be a guide to how this new and more fluid situation will develop. It is possible, though unlikely, that the coalition’s problems will be confined to constituency boundaries; it is also possible that the Liberal Democrats will leave office before the end of the Parliament in a way which affects the fortunes of all three parties and their leaders. Past experience of British peacetime coalitions and minority governments is that they deteriorate and usually fragment because they can, where single party governments cannot afford to. That is not in itself good or bad; but it does look more likely.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr Matt Cole lectures at the LSE as a Visiting Fellow of the Hansard Society. He has also lectured in British politics at the University of Birmingham and at the Open University. He is the author of Richard Wainwright, the Liberals and Liberal Democrats(MUP 2011), completed with the co-operation of the LSE archives.

2 Comments