The UK’s Human Rights Act and international human rights legislation prohibit torture and returning refugees or asylum seekers to countries where they are likely to suffer torture or persecution. In a new report Catherine Ramos details the fate of Congolese asylum seekers who were forcibly removed from the UK and suffered inhuman treatment in the DRC, and argues that the UK should halt removals until returnees’ rights can be guaranteed.

When David Cameron addressed the Council of Europe recently to express the government’s ‘serious questions’ about the European Court of Human Rights he urged the body not to doubt the UK’s commitment to defending human rights, specifically claiming that ‘no decent country should deport people if they are going to be tortured.’ But for almost a decade concerns have been raised about the post-return experience of Congolese asylum seekers who have been refused sanctuary in the UK and removed to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

The UK has no system of monitoring the post return experience in place, although the Independent Asylum Commission recommended in its 2008 report Safe Return that every encouragement be given to:

“developing a system which enables some record to be maintained of the subsequent history of refused asylum seekers after return to their country of origin…. Where there has been persecution on return, knowledge of such persecution would contribute towards better decision-making in the future. It could also contribute towards ensuring that country of origin information is kept as up-to-date as possible.”

From 2007 Congolese clients of the charity Justice First began reporting their imprisonment and ‘ill treatment’ after removal to the DRC and their post return experience began to be monitored. The monitoring refutes the UK Border Agency’s claim that men, women and children can be safely removed back to DRC and is documented in a new report Unsafe Return

Unsafe Return details how 17 asylum seekers have had their human rights violated upon return; some have been imprisoned in the Congolese secret services prisons and, in other cases, have simply disappeared. Two men that had returned voluntarily had been imprisoned or threatened. A third voluntary returnee removed with her child is untraceable.

The refused asylum seekers have stated that they were accused of being traitors, of having betrayed both the country and the President, of having said that there were no human rights in the DRC. They allege they were tortured to make them name others involved in perceived anti-government activities in the UK. Guards and those charged with interrogation accused returnees of coming from the UK where people speak ill of the President and three were accused of having attacked President Kabila’s Minister, She Okitundu, in London and tortured so they would name others.

A Congolese Immigration officer interviewed for the report explained the process of receiving those who are refouled (returned to persecution or risk of serious harm, as prohibited under international law) as follows:

- The UK Immigration authorities contact the Congolese Immigration authorities prior to the removal of asylum seekers and the names of those to be removed are given.

- The Immigration services in DRC will study and analyse the returnee’s file in their possession in order to establish whether the returnee has a ‘problem’ with the Congolese state, such as a breach of state security.

- In such a case the Immigration Service will contact the Security Services.

Once the Immigration authorities know the returnee has arrived at the airport, they go immediately to pick him or her up for interrogation. If the person has a political problem s/he will be ‘put’ where people who have problems are ‘kept’. Returnees were sent previously to Kin Mazière prison and now to Tolerance Zero. People are imprisoned and can be killed in Tolérance Zero. Punishment does not take place at the airport but in secret – ‘behind the scenes’.

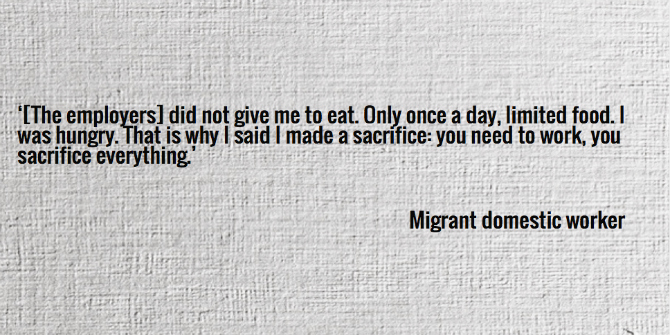

The methods used to extract information about activities in the UK amounted to torture: severe beating, electrocution, rape and sexual abuse. Returnees were held without access to a lawyer or to visitors in prisons where conditions are recognised as breaching human rights conventions. One male returnee reported:

“It’s was an awful experience: very bad condition of life because have to pee and to eat, to sleep at the same room and on the floor. No food was been given and sometimes we were forced to drink our own human urine and were beating [sic].”

Of the nine children removed with their parents to DRC, six had been imprisoned. Three siblings imprisoned with their mother had to be transferred urgently to hospital on the fourth day of their captivity due to severe dehydration. UNHCR staff state that removed asylum seekers do not come under their mandate; their interest ceases once an asylum seeker is removed from the country. There appears to be a lack of transparency regarding the fate of returnees and about the actual monitoring being carried out by international organisations that the UK government relies on for independent evidence.

Politicians may be turning the other way when faced with unpalatable foreign policies which allow for the developed world to benefit from the plundering of the DRC resources. They may wish to feign ignorance about the fate of Congolese people who had sought protection here. But as was noted by William Wilberforce, when addressing fellow Parliamentarians on the issue of slavery, ‘You may choose to look the other way but you can never say again that you did not know.’

The Unsafe Return report can be found on the Justice First website. An e-petition has been set up as a result of the report and requires 100, 000 signatures if the issue of refused asylum seekers from the DRC is to be considered for debate in Parliament.

Please read our comments policy before posting

About the author

Catherine Ramos – Justice First

Catherine Ramos is a language teacher and interpreter, with a special interest in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. She is currently active as the honorary secretary of Justice First and also acts in a voluntary capacity helping people seeking asylum deal with any problems as they integrate into the local community