Contrary to popular narratives that see Margaret Thatcher as the cause of Conservative decline in Liverpool, David Jeffery explains that various other factors were in play, long before Thatcher came to power. Those factors, combined with the rise of the Liberals in the 1970s, displaced the Conservatives as the main local opposition to Labour.

Contrary to popular narratives that see Margaret Thatcher as the cause of Conservative decline in Liverpool, David Jeffery explains that various other factors were in play, long before Thatcher came to power. Those factors, combined with the rise of the Liberals in the 1970s, displaced the Conservatives as the main local opposition to Labour.

Theresa May’s Conservatives have consistently been polling well ahead of Labour. Unsurprisingly to most, none of the predicted Conservative seats are in Liverpool. The accepted cause of this dearth of Tory seats is clear – to paraphrase the Sun (which you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone in Liverpool reading), ‘it was Thatcher wot lost it’. However, as I show in my article in British Politics, ‘The Strange Death of Tory Liverpool’, the reality is more complex than this.

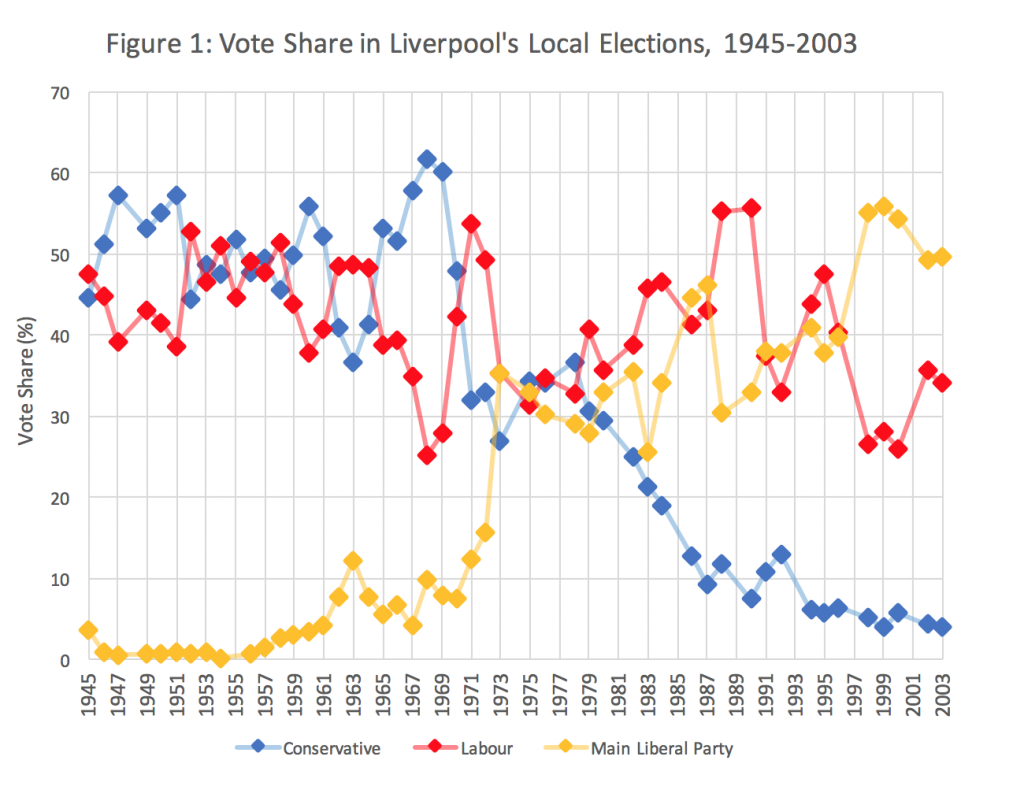

As shown in Figure 1, post-war Conservative fortunes in Liverpool can be split into three distinct periods; success (1945-1970), decline (1970-1987), and irrelevance (1987 onwards).

Source: Rallings et al (2006)

Source: Rallings et al (2006)

Success: 1945-1970

Until the early 1970s, the Conservatives were one of the two big players in Liverpudlian politics, running the council from the mid-19th century until 1955, 1961-1963, and 1967-1972. The Tories benefitted from the hangover effects of the Protestant-Catholic sectarian divide which gripped the city in the pre-war period. This framed the city’s electoral politics, with Protestants voting for the Conservatives whilst Catholics voted Liberal in the nineteenth century, before moving to the various Catholic parties in the city, and finally to Labour from the 1920s.

Even after class replaced religion as the main driver of voting behaviour in the inter-war period, we do not see a sudden – or even gradual – swing towards class-based voting in Liverpool. Instead, the Conservatives could rely on political socialisation – the process whereby an individual’s political beliefs, outlooks, and other related values are shaped by the environment in which they find themselves, especially during their formative years. In the case of Liverpool, those who grew up in a Protestant-Tory area would be socialised into voting Conservative, and thus perpetuate the Conservatism of an area. Their children would also be socialised into voting Conservative, but this would no longer be directly because of Protestantism.

If socialisation provided the base of Conservative support, local issues and national government performances help to explain the swings in party support. It is no coincidence that the Liverpool Conservative’s strongest periods, 1946-1951 and 1965-1970, were during periods of Labour government, as local elections were used to register dissatisfaction with the government.

Decline: 1970-1983

Accepting that governing parties tend to do worse in local elections, the drop in support for the Conservatives from 1970 to 1973 does not seem unusual. However, why is there no Conservative resurgence during the Wilson and Callaghan governments? Answer: the rise of the Liberals.

By 1970, both the local Labour and Conservative parties were hollow shells, unresponsive to the needs of the voters. The Liberals, with their emphasis on ultra-local issues (dubbed ‘pavement politics’), were the perfect contrast and managed to win votes from both Labour and the Conservatives – although they were much likely to win in Conservative wards.

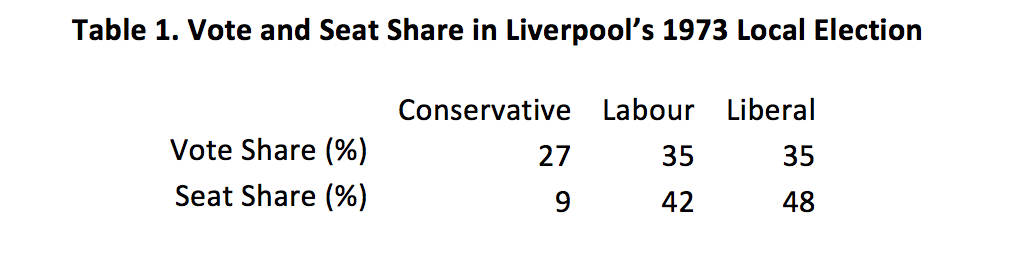

However, it is possible that the Tories could have seen off the Liberal challenge, were it not for the 1973 local election, which was an all-out election due to local government reorganisation. The election was a perfect storm; dissatisfaction with the Heath government, locally unrepresentative parties, and the Liberal’s aggressive campaigning resulted in a Liberal surge, from 16% of votes in 1972 to 35% in 1973 and, as shown in the table below, pushing the Conservatives into third place.

Table 1. Vote and Seat Share in Liverpool’s 1973 Local Election

Hence, the Liberals could blunt the Conservative claim that only the Tories could beat Labour in Liverpool during the Wilson and Callaghan governments. Due to the Conservative’s inefficient spread of votes, apart from 1978, they never again beat the Liberals in terms of seat share, despite often win more votes. This prevented the Conservatives from staging a resurgence in the council chamber.

Hence, the Liberals could blunt the Conservative claim that only the Tories could beat Labour in Liverpool during the Wilson and Callaghan governments. Due to the Conservative’s inefficient spread of votes, apart from 1978, they never again beat the Liberals in terms of seat share, despite often win more votes. This prevented the Conservatives from staging a resurgence in the council chamber.

Thatcher’s election in 1979 resulted in the familiar drop of support for a governing party in local elections, with Conservative vote share falling from 31% in 1979 to 21% in 1983. However, decline is the not the same as irrelevance. There was no reason why the Conservatives could not recover from their nadir, as they had in the 19th century. However, the reason they did not recover from decline, and did become irrelevant, can be pinned on Thatcher.

Irrelevance: 1983-Today

The Scouse identity is the key factor for the electoral irrelevance of Conservatives to Liverpool. By the 1980s Liverpool was in a bad way both economically and socially, synonymous with unemployment, crime and drugs, and the Thatcher government was in conflict with the Militant-led Labour council, who were successful in framing the debate as one of Liverpool vs. the Tories.

Tajfel and Turner argue that identities are a key way in which individuals maintain or enhance their self-esteem. If an identity is negatively portrayed by out-groups – such as the Scouse identity in the 1980s – the in-group can engage in what is termed ‘social creativity’, changing what counts as ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. For Scousers, this involved rejecting key tenets of Thatcherism, such as competition, the free market, and private sector, and emphasising the mythologised Scouse traits of ‘solidarity’ and ‘justice’, which were seen as anathema to Thatcherism.

This is important for electoral behaviour since identity shapes group norms, or the accepted behaviour of members of that identity group. The anti-Thatcher element of the Scouse identity had led to the norm of ‘real Scousers don’t vote Conservative’. A recent example of this mindset can be found in the comments of an article in the Liverpool Echo about the unveiling of a statue Conservative-supporter Cilla Black. The paper surmised that “Many of you felt Cilla Black’s support for the Tory Party… means she should not be celebrated in Liverpool.”

This norm was reinforced through socialisation. However, unlike the socialisation which maintained Conservative support until 1973, this socialisation faced fewer sources of restraint. As the Liberals and Labour could thrive within the confines of an anti-Tory Scouse identity, and the Conservatives were electorally irrelevant, there was no political resistance, and culturally the city has embraced anti-Conservatism with pride.

Lessons

The potential for the Liverpool Conservatives to ape the process of Conservative rebirth seen in Scotland under the leadership of Ruth Davidson is dependent on their ability to make themselves compatible with Scouse identity. The likelihood of this is not high. The Scottish Tories have capitalised on being the only party squarely on the side of Unionist voters in Scotland, whilst the only new cleavage open in Liverpool – the Remain-Leave cleavage arising from the EU Referendum – seems less fruitful for May’s Conservatives, with Liverpool voting 58% to remain. Until the Conservatives find a way to work within the confines of the Scouse identity, they are unlikely to achieve much in terms of electoral success in Liverpool.

______

Note: the article draws on the author’s published work in British Politics.

David Jeffery is a doctoral researcher at Queen Mary University of London, researching Conservative decline in Liverpool. He can be found tweeting too much @DavidJeffery_.

David Jeffery is a doctoral researcher at Queen Mary University of London, researching Conservative decline in Liverpool. He can be found tweeting too much @DavidJeffery_.

I am responding to this rather sketchily for which I apologise.

You touch on the Orange/Tory vote. The events in Ulster of the few years after 1969 surely had an effect. The rise of Irish Republicanism manifested itself in the communal strife in Belfast. Hundred of women & children were evacuated to Liverpool from Belfast.

The expectation that the Tories would deal more effectively with the lawlessness. However they became seen as the party of appeasement originally tolerating and then only acting against the “no-go” republican areas after pressure from Protestant areas with their replication of the barriers.

A similar effect was felt in the West of Scotland.but not to the same degree as there had never been, post-war, the same closeness between the Orange Order and Conservatives

Once small business and other local business Fail, moved or taken over, the middle class voters move away. This is also part of the slow decline of the Tory’s in Liverpool.

When Trevor Jones raise the Liberal Flag over the Town Hall he claim to the middle class that the was still hope. His famous 1p in the pound cut in the rates swung the votes his way. Trevor and Thatcher cause the rise of Hatton as the anti Blue and Yellow mix.

After 1981 that was the beginning of no return the Tory’s. The riots, the claims that Thatcher want to close the city.

Another dream that turn into a nightmare was they remove the Merseyside Country Council. Until then with Southport and the Wirral they had a voice. Due to Thatcher rows with GLC, Metropolitan Country Councils were scrap. This made people see her as a Dictator type PM.

The Poll Tax was another kiss of death for the Tory’s in many Labour Area’s.

The final nail was Hillsborough her support for the S## pull the rug from under them.

Now only Southport has a Tory MP for how long only time will tell.

As a scouser born in the 30’s but not bred I had a large extended family there and often visited. Wilson worked the area hard to turn the marginals, I knew his agent. I recall being with him in Director’s boxes at Goodison and Anfield. During this period there were major population shifts notably people buying their own houses needing to cross the boundaries to go elsewhere. One aspect is the effect of the 1973-4 Local Government Reorganisation. I was involved in a similar situation in Yorkshire. It upset a lot of applecarts, and the boundaries drawn had an effect. The local Conservatives, largely small business people now often struggling, wanted caution and limited spending. The Labour and Liberals were quite the opposite. So when Thatcher arrived Liverpool, now big spenders were among the biggest of the losers.