Or Tuttnauer, Tom Louwerse, Rudy Andeweg, and Ulrich Sieberer analyse opposition party sentiment in relation to government actions and policies during the first six months of 2020. Drawing on parliamentary debates in four countries, including the UK, they observe an initial positive opposition sentiment which turned more negative as the first wave abated.

With the challenges presented by the Omicron variant, the UK government – as other governments around Europe – reintroduced restrictions and measures to further fight the pandemic. Enacting these measures has frequently required cooperation on the part of the parliamentary opposition. Even if not needed to enact rules or legislation, opposition support may be important for legitimising such measures and facilitating their success. This raises the question of how opposition parties react to such a crisis. Do they support the government in a shared effort to face a common threat? Or do they capitalise on the opportunity to criticise the government’s alleged shortcomings, backed by the constant flow of negative news?

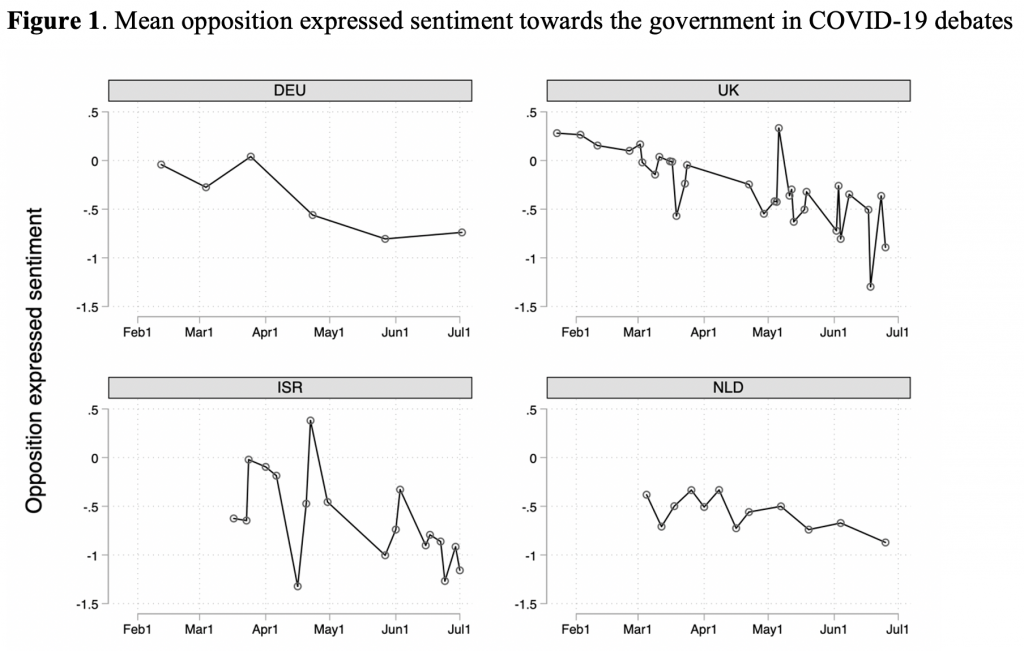

We studied this question earlier in the pandemic, looking at how opposition parties in four countries (the United Kingdom, Germany, Israel, and the Netherlands) reacted to government actions during the first six months of 2020. We found evidence of an elite ‘rally around the flag’ early on, with positive opposition sentiment towards the government, which turned more negative in the following months. Does this mean that the relationship between government and opposition structurally changed during the early changes of the pandemic? And how will relations develop beyond the first wave of COVID-19?

Opposition during a crisis

In early 2020, the pandemic presented a unique crisis situation: primarily a public health crisis, but with important social and economic consequences. It directly affected not only the daily life of citizens but also the work of parliament. Many parliaments scrapped most debates about non-COVID topics, went partially virtual, and in some cases also changed voting procedures and/or the frequency of parliamentary votes, impacting the way in which governments could be held to account during the first stages of the pandemic.

In terms of democratic norms, government-opposition relations in times of crisis can have contrasting expectations and effects. On the one hand, government-opposition consensus on crisis measures increases their legitimacy among the public. On the other hand, criticism by the opposition is important as a catalyst for public discourse, which is vital for democracy especially in times when governments are prone to seek more powers. It is therefore important to understand how opposition parties behaved during the first months of the COVID-19 crisis. To this end, we analysed opposition parties’ speeches during pandemic-related debates during the first six months of 2020 in the four countries mentioned. These cases provide us with a diverse set of established democracies in terms of their political institutions and the overall severity of the crisis (at the time).

We focused on statements regarding the government’s actions and constructed a sentiment scale, ranging between strongly negative (using blunt language or personal attacks) to strongly positive (giving praise to specific government actions). We manually coded each paragraph according to our scale and used the average score of all speakers who spoke on behalf of their party on a specific day.

Rally around the flag

In line with a ‘rally around the flag’ effect in public opinion, we saw that most opposition parties reacted in a relatively positive manner in the early stages of the crisis (see Figure 1). The average sentiment towards the government became increasingly negative in each of the four countries as the COVID-19 crisis developed. The decreasing pattern is most clear for Germany, while for other countries there is more variation around an otherwise clearly negative trend. The estimates for the UK and Israel include a number of days with relatively short debates, which explains the larger variation.

Comparing opposition sentiment during the first wave of COVID-19 to a sample of pre-pandemic speeches, we find that the sentiment expressed by the opposition in March and April 2020 is clearly more positive than in these baseline speeches. Expressed sentiment in the later pandemic-related debates is generally much closer to the baseline levels.

Less adversarial

Focusing on the UK, the cooperative approach was acknowledged during the very first debate on COVID-19 in the Commons by the then Secretary of State for Health, Matt Hancock, who said: ‘I appreciate the cross-party approach that is being taken to this outbreak as reflected in the shadow Minister’s remarks.’ (January 23, 2020). This less adversarial style cannot be explained by the policy area concerned: the NHS is frequently the topic of fierce disagreement in British politics. Now, such disagreement was referred to only obliquely. On February 3, Jonathan Ashworth, the then Shadow Secretary of State for Health, commented, for example, that ‘This is a time of considerable strain on the NHS. I know the Secretary of State and I disagree on why this is, but he will accept that it is a time of high pressure.’

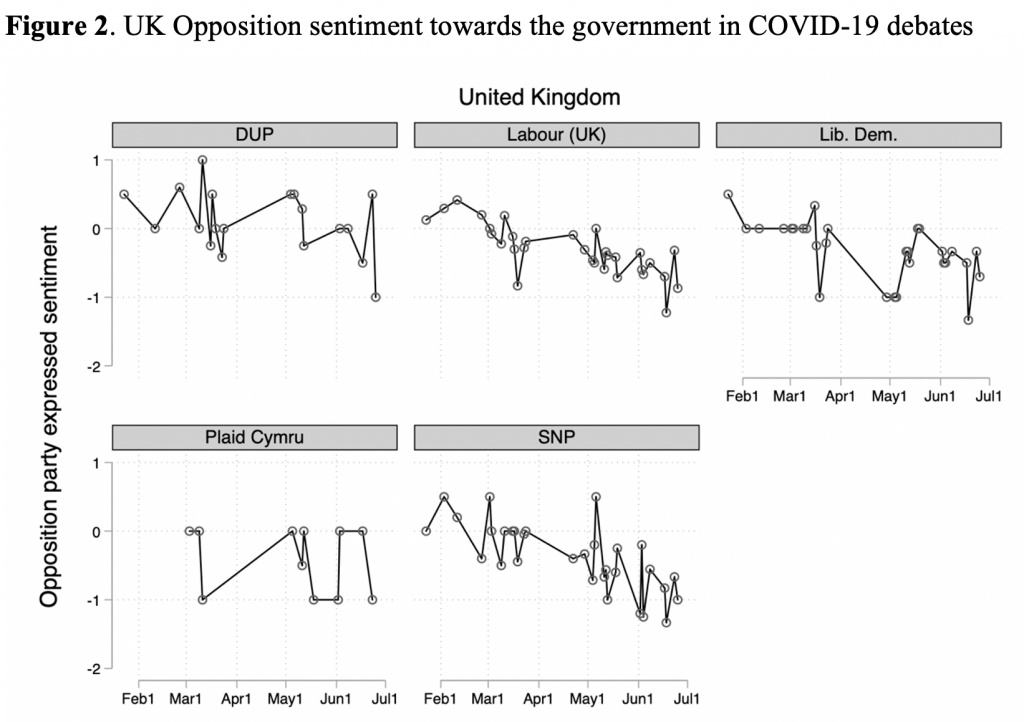

As Figure 2 shows, the gradual erosion of support for the government’s approach to the crisis is – more or less clearly – visible for all opposition parties (with the exception of Plaid Cymru). This shift among opposition parties occurred even before the heat of the crisis was over. This may be related to the fact that while most of the early debates dealt with the public health response to COVID-19, gradually other policy domains became involved as well, such as the package to support businesses and prevent mass unemployment, and the disproportional impact of the pandemic on the ethnic minorities. On such issues, ideological distinctions may have prompted more negative rhetoric even early into the crisis.

Party differences

We also observe relevant differences between opposition party sentiment on COVID-19. The usual factors affecting the opposition’s attitude toward the government in general – party ideology, size, and prior government experience (see, for example this study) – played their typical roles also in the debates about COVID-19, even in the earliest stages of the crisis. Larger opposition parties with considerable prior government experience were more positive during the early stages than parties without such experience. Among parties without prior government experience, larger ones were more negative than smaller ones. Ideological divergence from the government also increases negativity, but the effect is insignificant when all other factors are taken into account.

Therefore, although we observe more positive opposition expressed sentiment early on in the COVID-19 crisis, we find little indication that government-opposition relations have changed qualitatively due to the crisis.

A politicised pandemic

So, what can we glean from these results about the expected relations between government and opposition in dealing with the current wave of the pandemic? We do not expect another ‘rally around the flag’ in parliamentary politics. The crisis is no longer ‘new’, parties on both sides have had time to politicise pandemic-related issues, and many debates around the handling of the pandemic now seem to speak more to longstanding ideological differences than was the case in early 2020. The relatively quick regression from a cooperative discourse back to a more confrontational one, as early as in the second quarter of 2020, suggests it will probably take a new and different crisis to initiate another spell of government-opposition cooperation. While one can express concern over the polarisation of the public debates on COVID-19 measures and vaccination mandates, a critical, confrontational opposition is not necessarily a bad thing as long as it offers voters a credible alternative in terms of how the authorities deal with the COVID-19 crisis.

______________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in West European Politics.

Or Tuttnauer is Alexander von Humboldt Fellow in the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research at the University of Mannheim.

Tom Louwerse is Associate Professor of Political Science in the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University.

Ulrich Sieberer is Professor of Empirical Political Science at the University of Bamberg.

Rudy B. Andeweg is Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Leiden University.

Photo by Branimir Balogović on Unsplash.