Genevieve Gorrell discusses the impact of COVID-19 on the verbal abuse politicians receive on Twitter. She finds that while this kind of abuse appeared to reduce in conjunction with the pandemic, the number of tweets refuting the existence of the virus were numerically significant, as were tweets attacking China.

Genevieve Gorrell discusses the impact of COVID-19 on the verbal abuse politicians receive on Twitter. She finds that while this kind of abuse appeared to reduce in conjunction with the pandemic, the number of tweets refuting the existence of the virus were numerically significant, as were tweets attacking China.

Twitter has become a favoured communication channel for politicians around the world, providing a direct, immediate way to communicate their message. The benefits are equally available to their audience, who can use the platform to engage with politics and share their opinions of policy and policy-makers on a public stage. Sadly, however, the tone is not always civil. Furthermore, under the shield of anonymity, Twitter users may engage in hate speech and threats towards others. Where politicians are subjected to this harrassment it may affect democratic representation; and what happens online can have violent consequences offline.

In this article we discuss our recent study of Twitter abuse in replies to MPs from February 7 to May 25 2020. Our method detects linguistically explicit verbal abuse; e.g. that containing slurs such as “moron”, or offensive words teamed with identity terms, such as “effing Tory”. Slurs and identity terms include words relating to different genders, races, religions, sexual orientations and ideological positions, but in fact most of the abuse we detect is general incivility such as “f**k off” and “idiot”. This approach gives a conservative figure for the actual amount of verbal abuse, which may amount to as much as twice the figure we detect. Using this method, at its peak in mid-2019 we found abuse in over 5% of tweets to MPs, having risen from less than 3% in 2015. In fact, Twitter attention tends to focus on the handful of individuals most in the public (or at least the Twitter) eye at the time. Most MPs receive much less abuse than that, but we routinely found abusive tweets in excess of 8% of replies to Prime Minister Boris Johnson and then-opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn. Politicians who receive more replies on Twitter also receive a higher proportion of abuse; whilst Twitter attention concentrates itself on a minority of individuals (it appears to be Zipfian), abusive attention does so to an even greater extent.

With a rising trend largely unbroken since David Cameron was prime minister, as 2019 drew to a close it was unclear to what extent specific events caused escalating abuse levels, as opposed to more general social and technological tendencies. The decisive Conservative victory in the general election settled a number of political open questions, and abuse levels toward MPs had already begun to fall prior to the appearance of COVID-19 in the UK. In February, Boris Johnson received lower levels of abuse than he had typically been receiving in 2019, though Jeremy Corbyn continued to receive high levels.

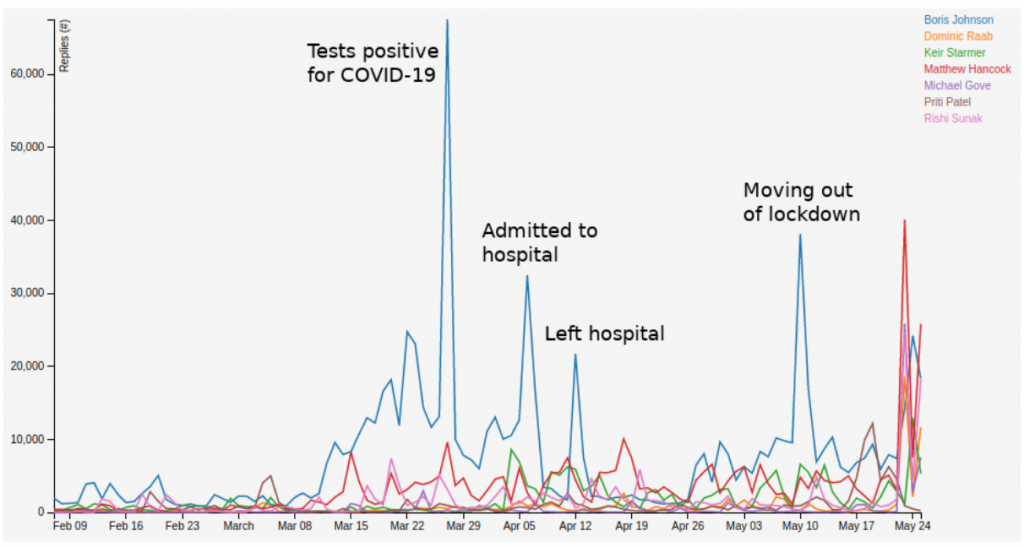

In March, attention shifted to COVID-19. With the start of the pandemic we see a high level of focus on Boris Johnson. As lockdown proceeded, attention shifted from Labour politicians to those Conservative politicians with a role to play in steering us through the crisis. Although there was some tension around policy decisions, with pro-lockdown hashtags dominating in March, politicians receiving more COVID-19 attention (as determined by proportion of replies containing explicit mentions of COVID-19) have tended to receive proportionally less abuse.

Boris Johnson contracted the virus in late March. This event led to the single greatest spike in Twitter attention of the period: he received a large number of replies to his tweet announcing his illness, and the replies were generally civil (2.3% abuse found). The various stages of Boris Johnson’s fight with COVID-19 attracted further spikes of interest on Twitter, as we see below.

Figure 1: Number of Twitter replies received by selected politicians

Moving into April, economy-related hashtags began to dominate, with #newstarterfurlough and #wearethetaxpayers peaking in mid-April. Abuse levels, however, remain low. Keir Starmer appears to attract less abuse than Jeremy Corbyn did in his role as Labour leader. Use of anti-lockdown hashtags, such as #endthelockdown, ramps up gradually throughout the month, and with Boris Johnson’s return to work at the end of the month, abuse levels have begun to rise as we move into May.

Use of anti-lockdown hashtags peaks in early May, with an additional mid-May spike, and remains substantial for the remainder of the study period. We also see in the timeline a buzz of attention on Conservative ministers towards the end of the study. This arises from Dominic Cummings’s trip north in the early stages of his own COVID-19 illness. Several ministers tweeted to defend his actions, and these tweets tended to attract abusive responses; “#sackcummings” and variants were dominant hashtags in late May. In the final week of the study we find 4.8% abuse, making it the most abusive week of the study,

So across the board, COVID-19 has not led to higher proportions of abuse on Twitter for MPs. Yet, in various ways, our findings are best explained by varying degrees of engagement by different societal groups. The comparatively positive response to Boris Johnson might be explained by more people replying to him than would normally do so; this extra attention was not abusive. The lower levels of abuse received by MPs who receive more tweets mentioning COVID-19 might also be explained by different people replying to politicians than usually would. A particularly striking illustration of this comes from tweets to MPs using the hashtag #newstarterfurlough and variants. People who had recently started a new job “fell through the cracks” for financial support from the government. With 56,000 tweets to MPs using #newstarterfurlough and variants (compared with only 21,000 using #stayhomesavelives and variants), #newstarterfurlough is the dominant hashtag campaign of the period. Given that those individuals are in an unfortunate position, it is all the more surprising to find that only 0.4% of those tweets contained abuse. The likely explanation is that the “new starters” are a broader, and more polite, cross-section of society than people who usually reply to politicians on Twitter.

In contrast, tweets containing #stayhomesavelives and variants contained 6.0% abuse. Tweets containing hashtags refuting the very existence of the virus, for example #scamdemic and #hoaxvirus, contained 7.8% abuse. Tweets describing COVID-19 as “Chinese”, e.g. containing #chinesevirus, contained 5.4%. Tweets found containing anti-lockdown hashtags contained 4.9% abuse.

We conclude, then, on a somewhat positive note, in that abuse toward politicians appeared to reduce in conjunction with the pandemic, and that the high abuse levels we have previously seen may not be representative of the majority. However, we also add a caution regarding misinformation and racism. In addition to the high abuse levels we see in tweets refuting the existence of the virus, we also find them to be numerically significant. Approaching 2,000 in number, these tweets are almost 10% of the number of those containing #stayhomesavelives and similar. Replies to MPs found blaming or attacking China approach 5,000 tweets.

_____________________

Genevieve Gorrell is a Research Associate in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Sheffield.

Genevieve Gorrell is a Research Associate in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Sheffield.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: by Morning Brew on Unsplash.