Looking at low income household indebtedness in austerity Britain, Hulya Dagdeviren and Jiayi Balasuriya find that the poorest households have experienced the greatest growth in unsecured debt to income ratio. More importantly, unlike the pre-crisis period when debt reflected a desire ‘to keep up with the Joneses’, in recent years there has been a rise in debt for essential needs such as rent, food and utilities.

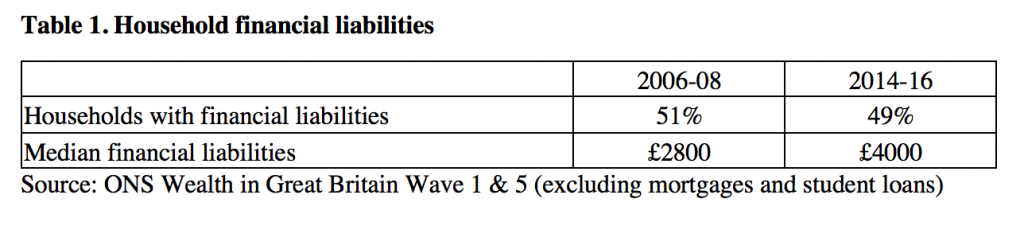

Unsustainable household debt was a major source of instability during the 2008 crisis. A decade after the crisis, one would expect a substantial deleveraging to take place across the economy. This is far from reality in Britain. In 2017, outstanding consumer credit was over £200 billion according to figures from the Bank of England. Longitudinal surveys revealed that while the proportion of households with financial liabilities (excluding mortgages and student loans) declined slightly in recent years and in comparison to the pre-crisis period, average household debt increased by around 43% (see Table 1). It is in fact more common for the unemployed and sick/disabled to be net debtor than employed and retired populations. Unlike the pre-crisis period when low income household debt reflected aspirations for home ownership, under austerity, debt or arrears for essential needs such as rent, food, energy and water account for a significant proportion of low income household indebtedness.

Indebtedness among low income households worsened

Indebtedness among low income households worsened

In our recent research we analysed a large and representative sample of UK society extracted from the UK Household Longitudinal Study and its predecessor, the British Household Panel Survey. These surveys, sampled before and after the financial crisis, collected information on debt in 2005-6 and 2012-3 from a total of more than 62,000 respondents and revealed the financial strain of the poorest households.

Compared to wealthier counterparts, low income households have had higher debt to income ratios over the past decade. On average 31% of the respondents reported having unsecured debt. While the unsecured debt of a typical individual in the top 10% income group has always been less than their monthly income, the debt-to-income ratio for the poorest 10% of the population grew from 140% in 2005-6 to 190% in 2012-2013, representing the largest growth in the degree of indebtedness in comparison to other income groups, a few years after austerity programme first rolled out. The proportion of individuals holding debt in the lower income groups also increased after the crisis as opposed to the contraction in the corresponding indicator for most above the average income groups.

Rising demand for debt advice corroborates the intensifying debt pressures amongst low income households. For example, the number of people who received debt advice from StepChange (a leading debt management charity, assisting mostly low income clients) increased six fold within a decade, rising from around 50,000 to 300,000 people between 2006 and 2016. In 2016, the charity was contacted by a record number of nearly 600,000 people for help, together with 3.3 million visits to its website.

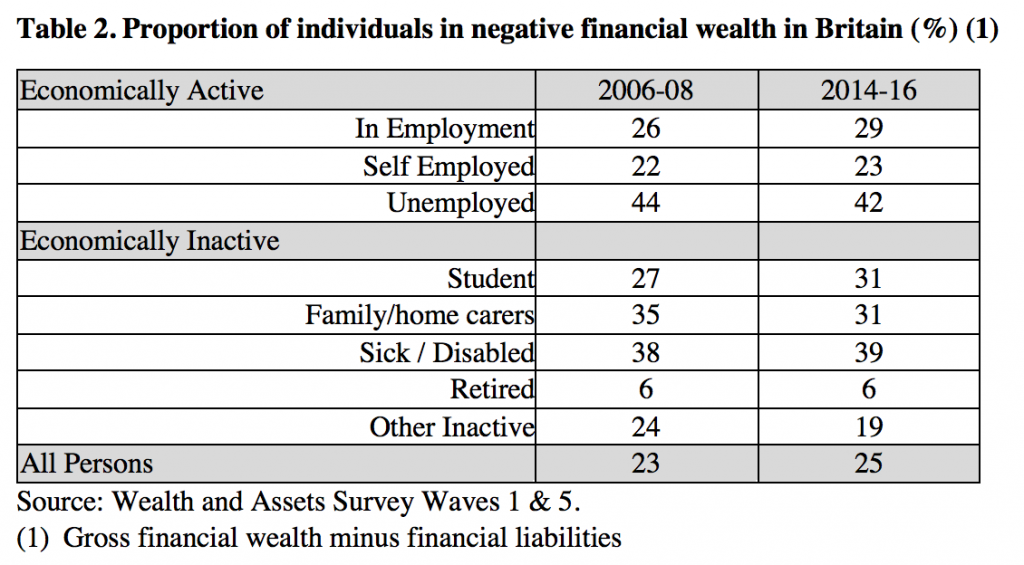

Debt and economic activity

Net financial wealth is an important indicator, reflecting the extent to which people are able to cushion their liabilities with their assets. Examining net financial wealth by economic activity reveals some remarkable dynamics with respect to household indebtedness in the pre- and post-crisis periods. Firstly, the proportion of employed and self-employed individuals in negative financial wealth (net debtors) has risen after the crisis. Secondly, and more importantly, those whose needs are supposed to be covered through the welfare state such as the unemployed, sick and disabled and their carers have been net debtors by greater proportion in comparison to other household categories. This was the case both before and after the crisis, reflecting the inadequacies of the welfare provision. To be precise, around 40% of unemployed and disabled population is in negative financial wealth.

Debt for essential necessities

An important element of low-income household indebtedness has been arising from difficulties with essential payments rather than the aspiration of households to accumulate assets or to keep up with their wealthier peers. This is reflected by UKHLS data on self-reported difficulties for paying rent or household utility bills. In 2012–13, several years after the austerity measures first rolled out, a greater proportion of the poorest households in the lowest 10% income category had arrears of essential bills. Over a fifth of the UKHLS respondents in that category found it hard to keep up with their housing payments, and around 18% were behind with payments for essential household bills. The rising debt for essential household spending is also confirmed by Citizens Advice and National Audit Office that provided a minimum estimate of £18 billion in personal debt owed to government, utility companies, landlords and housing associations.

The evidence from our research shows that while growth of household indebtedness prior to the crisis may have reflected a desire to accumulate wealth or maintain socially acceptable lifestyles, a different phase of indebtedness has emerged under austerity. The evidence from surveys, debt advice organisations, and interview data shows that low income households have been incurring debt for basic necessities and key services. This underpins the fact that debt is not always accrued from financial providers but also from non-financial companies providing services like water and energy, or local authorities providing social housing.

_____________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work (Sheila Luz, Ali Malik, and Haider Shah) in New Political Economy.

Hulya Dagdeviren is Professor of Economic Development at the University of Hertfordshire.

Jiayi Balasuriya is Senior Lecturer in Finance at Hertfordshire Business School, University of Hertfordshire.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

I would say that bankruptcy is somewhat problematic but the solution is always there for debt issues