Up until the 2015 UK general election, Scotland had been regarded as a Labour stronghold, with the country regularly returning a large number of Labour MPs to Westminster. But the party managed to secure only a single Scottish seat in 2015 and recent polls suggest its vote share could fall even further in the upcoming general election in June. Stuart Brown assesses where Scottish Labour voters have shifted their support to since 2015, and suggests the Conservatives could be the key beneficiaries if Labour’s vote share declines further in 2017.

Up until the 2015 UK general election, Scotland had been regarded as a Labour stronghold, with the country regularly returning a large number of Labour MPs to Westminster. But the party managed to secure only a single Scottish seat in 2015 and recent polls suggest its vote share could fall even further in the upcoming general election in June. Stuart Brown assesses where Scottish Labour voters have shifted their support to since 2015, and suggests the Conservatives could be the key beneficiaries if Labour’s vote share declines further in 2017.

Before the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, a popular line, repeated endlessly around general elections, was that if you pinned a Labour rosette on a donkey it would have a reasonable chance of being elected as an MP in Scotland. Even as late as 2010, at a time when Labour’s support was faltering across the rest of the UK, the Scottish vote held firm, with Gordon Brown leading the party to 42% of the vote and 41 of the country’s 59 MPs.

The story of Labour’s collapse in Scotland since that point, and the role of the independence referendum in pushing the SNP toward a near clean sweep of seats in the 2015 general election, is now almost as familiar to Scottish audiences as the donkey joke once was. But recent polling ahead of the snap general election in June suggests Labour’s decline still has some way to go. A poll released on 21 April by Panelbase, which showed the SNP leading on 44%, had Labour at an astoundingly low 13% of Scottish votes. Just as notable was that the Conservatives, after years of being viewed as something of a toxic brand in Scotland, were 20 points ahead on 33% – a situation that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago.

The Panelbase poll was at the low end of what Labour has been recording in Scotland over the last few months, but no major Westminster poll in the last year has put the party above 20%. The most relevant question ahead of the June election is arguably not whether Labour can mount a recovery in the short time available for campaigning, but which party stands to benefit most from the disintegration of their once large support base. This is of no small importance in what is fast becoming a race between the pro-EU and pro-independence SNP, and the anti-independence Conservatives, who have effectively been enshrined as the guardians of Brexit by Theresa May.

To illustrate the change in Labour support in Scotland, it is worth isolating two distinct periods. The first period entails the shift in support that occurred between the 2010 general election and the 2015 vote, which was heavily influenced by the fallout from the independence referendum in 2014. The second period covers events since 2015, which have been dominated by the UK’s EU referendum in June 2016, and the subsequent announcement by Nicola Sturgeon in March 2017 of her intention to seek a second independence referendum.

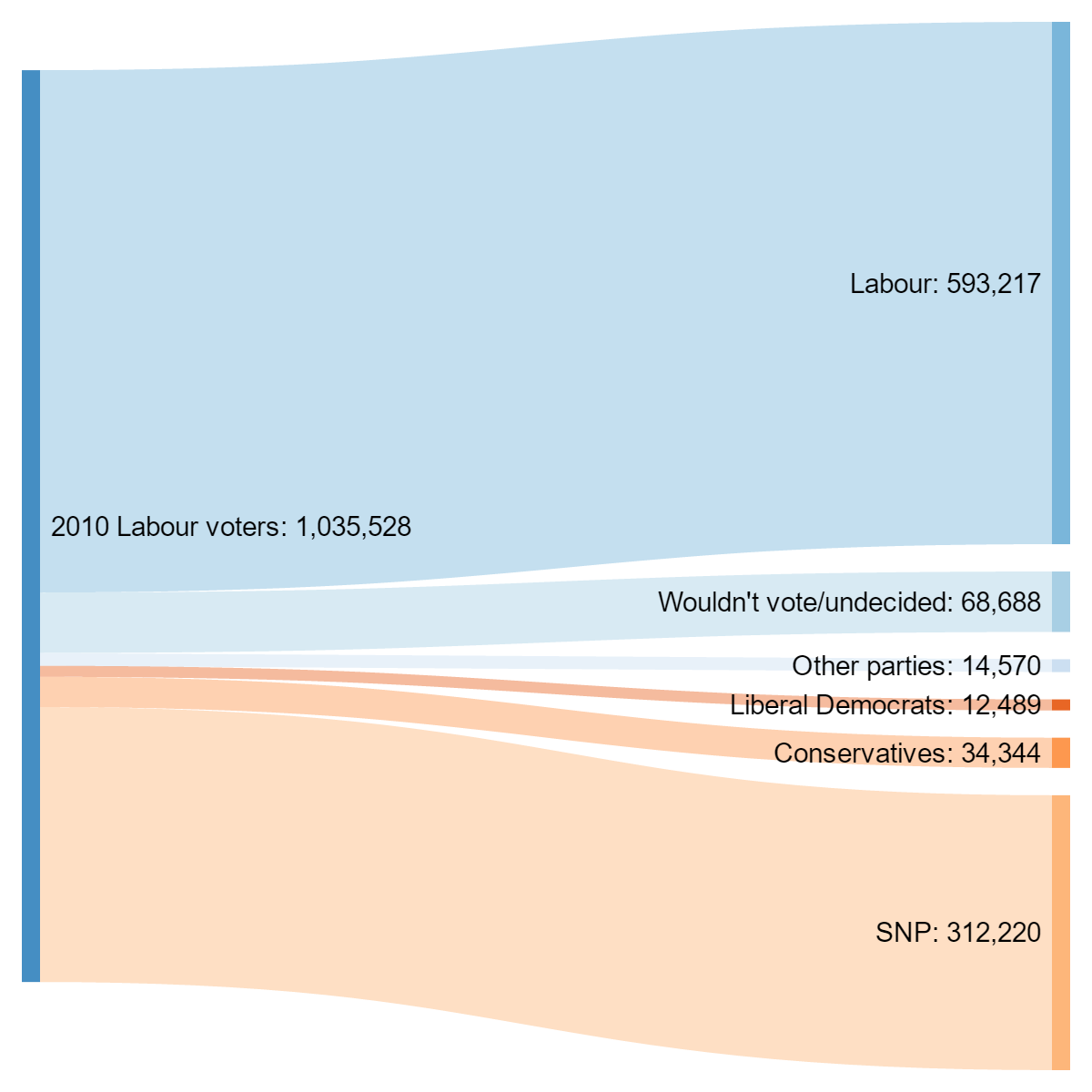

The figure below shows where Labour support was reallocated during the first period according to polling from Survation. The reason for using Survation figures is that they are the only polling company to have conducted a recent poll on Scottish voting intentions which also weighted 2015 polling responses according to the party respondents had voted for in 2010. The solid line on the left of the figure represents all of the votes Labour received in 2010, while the lines branching to the right show where this support was transferred in 2015 according to the polling.

Figure 1: How 2010 Labour voters shifted their support at the 2015 general election in Scotland

Note: Compiled by the author using polling figures from Survation (May 2015)

A few things are worth noting in this figure. The first is that the vast majority of Labour supporters who indicated they would switch party at the 2015 election moved their support to the SNP. In total, almost a third of 2010 Labour voters stated they would back the SNP, with one of the main dynamics at play being Labour’s loss of pro-independence voters following the party’s decision to campaign for a No vote in the independence referendum.

It should be emphasised that as these figures are based on polling responses, they only provide a rough estimate of where the 1,035,528 votes that went to Labour in 2010 were actually reassigned. The figure also doesn’t show individuals who decided to back Labour in 2015, but who had voted for another party (or did not vote at all) in 2010. In the end, Labour’s final tally of votes in 2015 amounted to 707,147, a vote share of just over 24%.

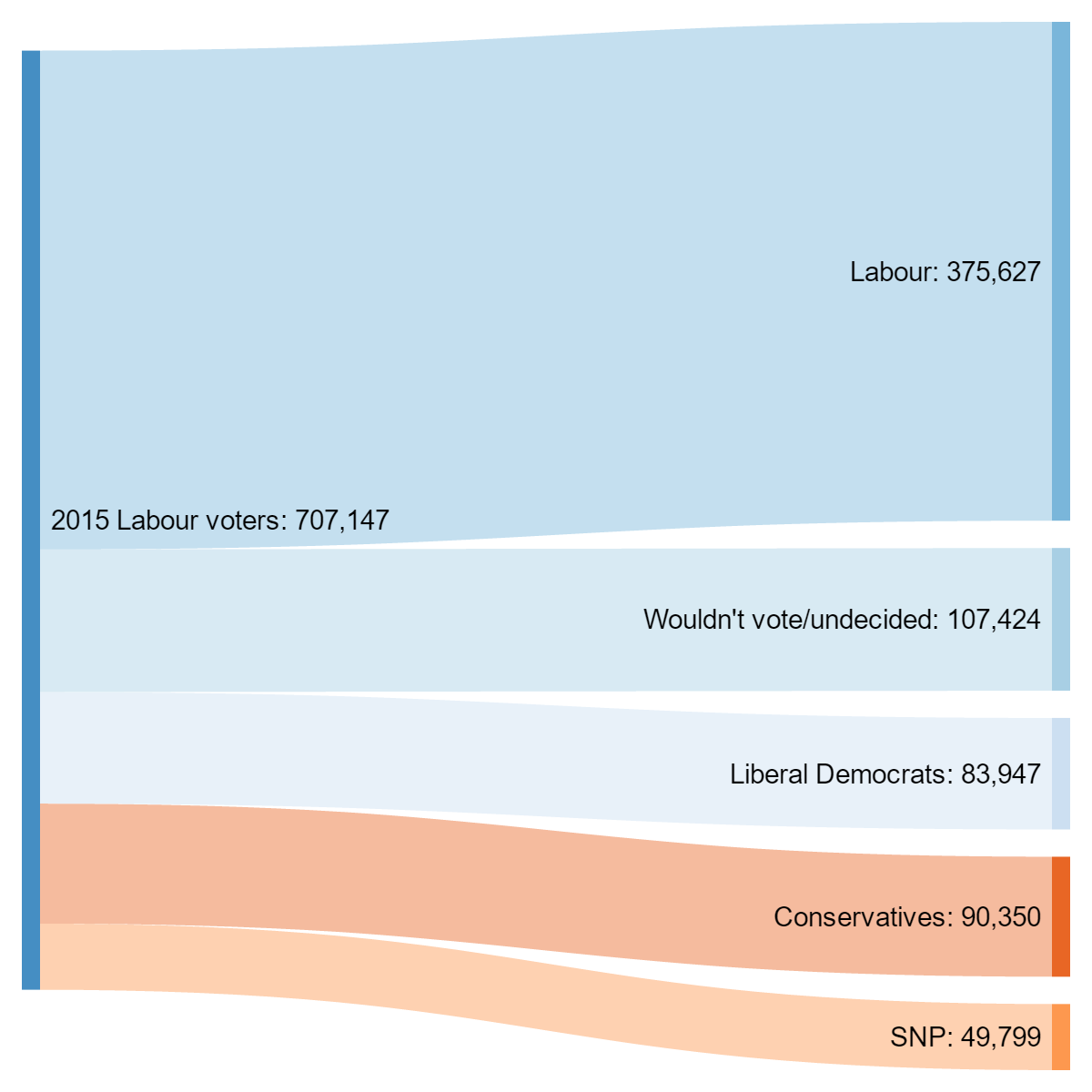

At the time, this was viewed as a catastrophic failure for the party, but if the polls are to be believed, the picture for the 2017 general election could be markedly worse. However, the change in Labour’s polling numbers since the 2015 election – the second period under consideration – has been altogether different. Figure 2 below conducts the same exercise as above using Survation figures from 21 April 2017.

Figure 2: How 2015 Labour voters could shift their support at the 2017 general election in Scotland (Survation poll, April 2017)

Note: Compiled by the author using polling figures from Survation (April 2017)

Remarkably, these numbers indicate Labour is on course to retain a lower percentage of its voters in 2017 than it managed to hold onto in 2015: around 57% of 2010 Labour voters said they would still back the party in 2015, while only 52.8% of 2015 Labour voters stated they would back the party in 2017. The relevant figures from the Panelbase poll released at the same time provide no greater cause for optimism, with only 46% of 2015 Labour voters opting to stick with them in 2017.

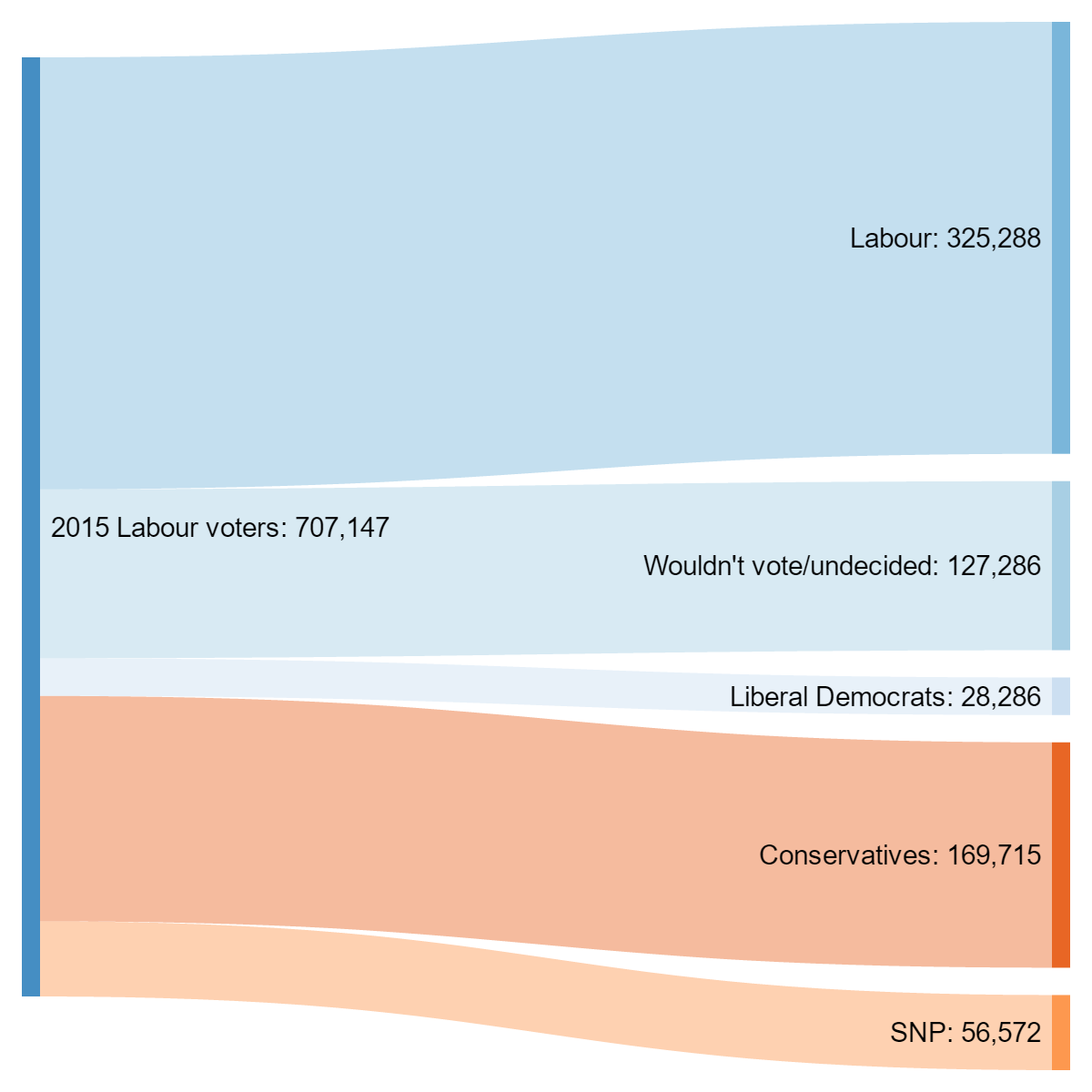

The most notable difference in the figure, however, is that there is now a more even split in terms of the parties that 2015 Labour voters would opt to switch to. Indeed, the SNP receives the fewest number of Labour deserters, with the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats standing to benefit to a greater extent. This may well be a function of the fact that most pro-independence supporters had already withdrawn their support for the party by 2015, but it also suggests there is potential for the Conservatives to pick up larger numbers of disillusioned Labour voters than was possible at the last general election. The Panelbase survey showed an even larger contingent of 2015 Labour voters (24%) switching to the Conservatives, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: How 2015 Labour voters could shift their support at the 2017 general election in Scotland (Panelbase poll, April 2017)

Note: Compiled by the author using polling figures from Panelbase (April 2017)

Both the SNP and the Conservatives appear to be in a far stronger position when it comes to retaining their 2015 voters: 87.6% of 2015 Conservative voters and 75.2% of 2015 SNP voters suggest they will stick with their choice in 2017 according to the Survation survey, while Panelbase records 89% for the Conservatives and 78% for the SNP.

The variations between the Survation and Panelbase polls demonstrate some of the obvious caveats with this kind of polling exercise. Scotland-only polls remain a rarity and subsamples of Labour supporters in such polls are relatively small. But the limited evidence we do have suggests that Labour’s loss of support in Scotland has continued in the two years since 2015, and that the Conservatives may well stand to benefit from the party’s troubles to a greater extent than the SNP – in direct contrast to what occurred in the 2015 general election. It says something about Labour’s demise in Scotland that its chief role in the 2017 election may well be as a third-party influence on contests between the SNP and the Conservatives, rather than as a direct contender to win the largest share of Scottish seats.

______

Note: this was originally posted one LSE EUROPP – European Politics and Policy. Featured image: CC0 Public Domain.

Stuart Brown is the Managing Editor of EUROPP and a Research Associate at the LSE’s Public Policy Group. He recently published a book on the European Commission, The European Commission and Europe’s Democratic Process (Palgrave, 2016).

Stuart Brown is the Managing Editor of EUROPP and a Research Associate at the LSE’s Public Policy Group. He recently published a book on the European Commission, The European Commission and Europe’s Democratic Process (Palgrave, 2016).

The rise of the SNP, and Labour’s wipe-out in Scotland, may owe a lot to the Scottish edition of The Sun throwing its support behind the SNP in the run-up to the general election in May 2015. At the same time the English edition of The Sun remained loyal to the Conservatives.

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/apr/30/scottish-suns-backing-for-snp-while-uk-edition-supports-tories-slammed

Alex Salmond seemed to think that support of The Sun in Scotland was important. Below is a quote from the article in the link above.

“It emerged during the Leveson inquiry into hacking that Salmond had heavily courted Rupert Murdoch, the News Corp boss, and his executives, after the Scottish Sun had published a hostile, anti-SNP front cover with a noose on it on the eve of the 2007 Holyrood elections.”

This second link to another article, by Ron Greenslade, explains Murdoch’s probable motivations for swinging the Scottish edition of The Sun behind the SNP before the 2015 general election.

https://www.theguardian.com/media/greenslade/2015/may/01/why-rupert-murdochs-sun-faces-two-ways-in-the-general-election

Here’s an excerpt from the article.

“In the first instance, it is further proof that Rupert Murdoch – who, as everyone knows, calls the political shots at his best-selling UK newspaper – thinks that his paper benefits from being on the winning side.

“Backing a winner confirms the rightness of the paper’s stance, thereby enhancing its status. That helps to retain and/or attract new readers. So it’s good for sales, and sales help to sustain advertising take. Commerce rules.

“As for the politics, the Sun/Murdoch is supporting the two parties on either side of the border with the greatest chance of defeating Labour. It is aimed at ensuring that Ed Miliband cannot obtain a majority.

“THE SUN REMAINS A UNIONIST NEWSPAPER, so it does not suggest any support for an independent Scotland. It’s all about who rules at Westminster. [My emphasis. The Sun in Scotland sat on the fence during the independence referendum campaign although a couple of years earlier it has supported the SNP in the Holyrood elections.]

“The cynicism? Well, that’s blindingly obvious. There is no principle involved. The Sun is published in the UK, but does not represent the UK.

“It is simply a profit-seeking vehicle that can be used by its owner to further his business and political interests.”

With the Conservatives tipped to take around 10 seats in Scotland in the general election it will be interesting to to if The Sun in Scotland decides that its support for the SNP has done its job, and it is now time to switch to backing the Scottish Conservatives again.

I think a bit of perspective is required when considering a supposed Scottish Tory revival.

In the 2015 Westminster general election the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party returned its worst ever result in Scotland, with less than 15% of vote. In 2016 it came third in the Holyrood election’s first-past-the-post ballot with around 22% of the vote. It came second in the party list vote largely because the Scottish Greens did well and reduced the Labour list vote.

In the 1950s (55GE, I think) the preceding party — the Scottish Unionist Party — took more than 50%, though in those days the voting age was 21.

The Scottish Conservatives’ share declined in part as a result of Scottish antipathy to Thatcherism and its economic effects in Scotland, especially deindustrialisation, and the apparent growth in support of social democratic arguments in contrast to neo-liberalism.

The 2015 election result in Scotland remains difficult to explain. The SNP hoovering up the Yes voters is the easy part. The large independence and/or social democratic-favouring section of the electorate being unimpressed by the Labour offer and, frankly, being unimpressed by the performance of many sitting Labour MPs and councillors in Scotland, is also fairly understandable.

But the atrocious Tory performance when, it has to be remembered, even Thatcher took percentages in the mid to upper 20s, and, it also had to be remembered, “No” had won the independence referendum by 10 clear points, is much more difficult to explain.

Now with the Independence/Union debate crystalising further, Scottish Labour in a decline it apparently won’t escape anytime soon, and the Conservatives in full campaign management mode it’s very likely the Tories will gain share of the vote and maybe a few seats in Scotland at GE 2017. But anything less than say 25% or 26% will be a very poor performance given the historical record and all the current circumstances.

The article graphically charts the decline of labour in Scotland but provides little in the way of explanation. Obviously their support for the Union and siding with the tories in th independence referendum plays major part and the article mentions that. However, the rot had set in before that – the referendum only came about because labour had already lost their holyrood majority to the snp. Since then, labour are perceived in Scotland as red tories – offering little more than token resistance to austerity and nothing more then ‘Snpbad’ as a policy platform in Scotland. Their inability to recognise this and change means they will never recover.

Just to give some colour to the article I can tell you about my family.

I voted Labour; however after Brexit I felt that the time had come to support independence so I switched to the SNP. I feel that Labour have become “no surrender” Unionists who put support for the Union ahead of everything.

My father voted Labour all of his life. He’s in his 80’s (doing well!) and is a huge supporter of the Union as someone who lived through the war. He’s switched to the Conservative & Unionist Party (as they use on the ballot paper in Scotland) because Labour are very shaky on the Union: their Deputy Leader backs “Home Rule”, the most senior Labour MEP is “undecided” on independence. Meanwhile the leader said she might support independence if Brexit happened, then said she’d misspoken but agreed that Scottish Labour MSP’s could have a free vote independence.

So in short, we’ve both left Scottish Labour for opposite reasons!

Given how wide of the mark all polls have been over the last few votes perhaps we should wait and see rather than speculate the outcomes on any poll.