Benjamin de Vet, Monica Poletti, and Bram Wauters examine the limits of party members’ electoral loyalty. They explain how strategic considerations, ideological discontent, and negative leadership evaluations lie at the basis of decisions to cast a defecting vote.

Benjamin de Vet, Monica Poletti, and Bram Wauters examine the limits of party members’ electoral loyalty. They explain how strategic considerations, ideological discontent, and negative leadership evaluations lie at the basis of decisions to cast a defecting vote.

One of the perceived advantages of having many grassroots members is that they supply political parties with a steady electoral base. Not only are members seen as ‘ambassadors’ on the ground that endorse the party in their everyday social contacts: they are also assumed to be loyal voters themselves, who support the party in both good times and bad.

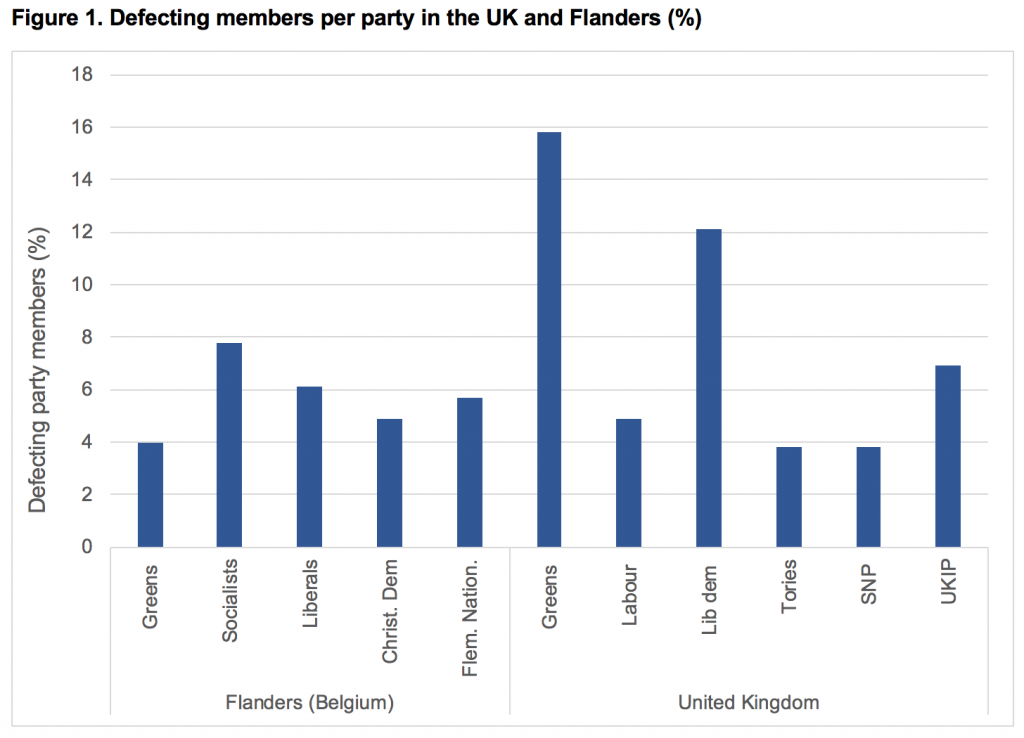

The electoral loyalty of party members should, however, not be taken for granted. Based on survey data of around 9,000 party members in the UK and Flanders (Belgium), we find that some vote for another party than the one they are member of. In Flemish parties, the percentage of disloyal members in the federal elections of 2010 and 2014 lies between 4% and 8%. In the UK, there is more variation. Larger parties, like the Conservatives, Labour, and the Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) saw between 4% to 5% of their members casting a defecting vote in the General Elections of 2015. This percentage is much larger in smaller parties like the Green Party (15.8 %), the Liberal Democrats (12.1%) and to a lesser extent UKIP (6.9 %). Virtually every defecting member of the Green party and half of the Lib Dems voted for Labour, whereas almost every defecting member in UKIP voted for the Tories. Note that our analysis only looks at members who actually voted for a (different) party, not at those who abstained from voting (which very few party members did in both countries).

Already from these numbers, strategic voting considerations seem to be an important factor at play. Party members might not sincerely vote for the party they genuinely prefer, but choose to vote for a party with a better chance of obtaining seats or being pivotal in coalition negotiations. Our explanatory analysis confirms the important role of strategic considerations, at least in terms of smaller parties being the victim of such judgments. This effect is, however, only found in the UK where its majoritarian electoral system decreases the likelihood for small parties to obtain seats, compared to Belgium’s proportional PR-system.

Strategic considerations aside, members’ disloyal voting behaviour is also caused by ideological concerns. First of all, members vote for other parties out of disagreement with their own parties’ ideological positions. Party members who perceive a large distance between their own and their party’s ideological stances (measured on a general left-right scale) are more likely to cast a defecting vote. Also the ideological appeal of neighbouring parties is important. Members who perceive a small distance between their own and other parties’ positions on a left-right scale are more prone to casting a defecting vote. Even though the fragmented multi-party system in Flanders decreases the ideological distance between parties, the effects of ideological concerns on members’ voting behaviour are equally substantial in British parties.

Lastly, leadership evaluations matter as well. In both countries, the more negatively a party member evaluates his or her party leader, the more likely it is that he or she casts a defecting vote. For members who are dissatisfied with the party leader, for instance because of his/her policy preferences or a member’s psychological attachment to another aspirant leader, voting for another party seems a tempting and less radical option than leaving the party. To some extent they remain loyal to the ‘party brand’, perhaps in the hope that one day the leader will resign. They might, however, once or as long as the party leader is in function, cast a defecting vote. Here again, we find a similar effect for British and Flemish parties.

Although a majority of party members do vote for their own party, our analysis shows that the loyalty of party members is neither absolute nor unconditional. A relevant share does defect at the ballot box, which poses a number of practical implications for parties. The strategic considerations of British members should be the least worrisome. Many ‘defecting’ members would probably vote for their own party if they lived in a constituency where the chances of winning a seat would be higher. As their voting decisions seems a pragmatic choice rather than one out of disagreement, they can possibly still act as ‘party ambassadors’, although they might find it more satisfactorily to do so online or in another electoral district.

More problematic is when party members defect because they have negative attitudes towards the party leadership, are displeased with the ideological direction the party is heading, or are attracted to ideologically close competitors. When party members are, in other words, dissatisfied with the current state of affairs within parties, they might not only deny them their own vote, but might also convince other party supporters to do the same. This could have a direct effect in marginal constituencies in majoritarian systems like Britain, but also in multiparty systems with small electoral margins like Flanders. More plausible, perhaps, is the long-term danger that if members remain dissatisfied for an extended period of time, they might consider leaving the party altogether. Notwithstanding some periodic ups and downs, this could further contribute to the widespread declining membership trend in Western Europe.

____________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in Party Politics.

Benjamin de Vet is a Junior Researcher in the Department of Political Science at Ghent University.

Benjamin de Vet is a Junior Researcher in the Department of Political Science at Ghent University.

Monica Poletti isESRC Postdoctoral Research Assistant at Queen Mary, University of London.

Monica Poletti isESRC Postdoctoral Research Assistant at Queen Mary, University of London.

Bram Wauters is Professor in the Department of Political Science at Ghent University.

Bram Wauters is Professor in the Department of Political Science at Ghent University.