The successive waves of strikes by public sector workers from a broad range of sectors testify to deep discontent but talks between the government and unions seem stuck in deadlock. Policymakers and economists disagree over what the impact of pay rises would be for inflation. Paul Whiteley looks at the data to determine whether fears of a wage-price spiral are well-founded.

The government still refuses to negotiate with public sector workers over pay despite continuing large-scale strikes. The reason given is that inflation will remain high or even accelerate if public sector workers are paid increases in line with inflation. Last year, Governor of the Bank of England Andrew Bailey made this claim and urged workers not to press for extra wages. Since then, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has made the same claim.

However, economists tend to disagree with this analysis because public services such as healthcare and education are free at the point of use. This means that consumers do not pay for them directly and so they do not affect the inflation statistics.

On the other hand, it can be argued that increases in public sector pay interacting with increases in private sector pay might end up boosting inflation. But does this actually happen?

Charting the relationship between public sector pay and inflation

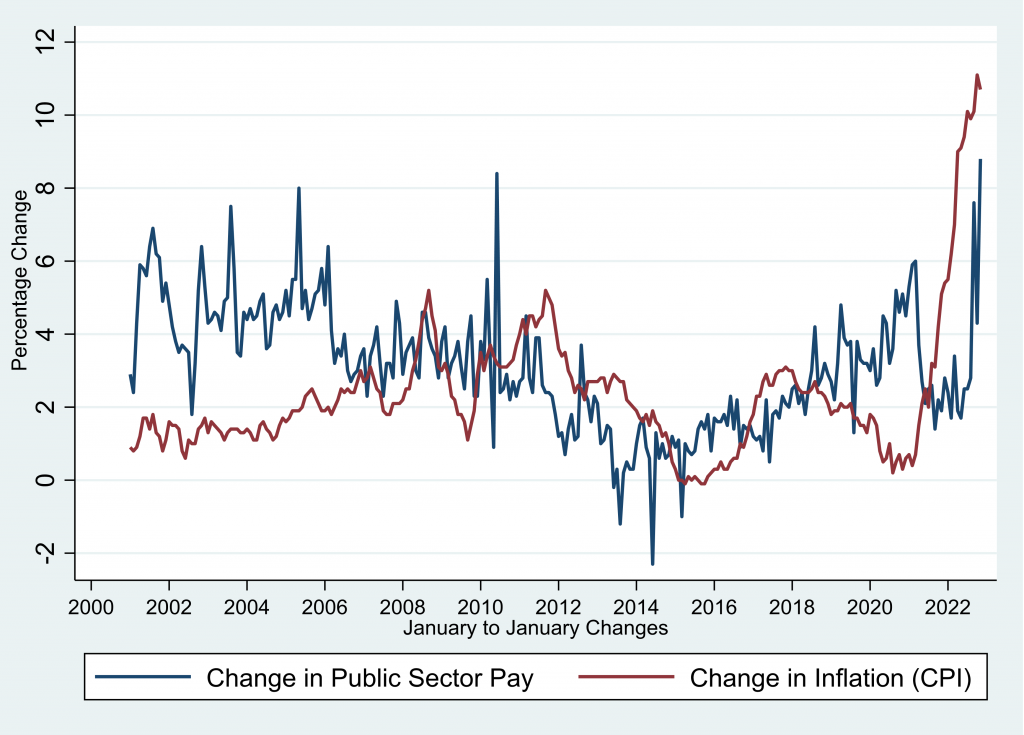

The graph below shows the relationship between changes in public sector pay and the inflation rate over a period of 263 months from January 2001 up to November 2022. It goes a long way to explaining why public sector workers are currently so aggrieved. The data comes from the Employment and Employee Types data collected by the Office of National Statistics.

During the period of the Labour government from 2001 up to the financial crash in 2008, public sector pay moved well ahead of inflation. At that time, standards of living for these workers were increasing at a significant rate. The financial crisis and subsequent recession changed things so that from 2008 to 2010 the gap between the two narrowed. But even then, inflation was below pay increases except for a brief period in early 2009.

This all changed after the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government came into office following the general election of May 2010. The new government embarked on a policy of austerity which involved severe spending cuts, and a freeze on public sector pay. As a result, pay fell well below the inflation rate. This situation continued right through to the 2015 election. In March 2015, two months before the election, inflation fell to zero while public sector pay fell by 1 per cent. At the same time, in that month private sector pay increased by 5.4 per cent.

The pattern of public sector pay falling behind the private sector continued after the 2015 general election and was only mitigated by inflation occasionally falling to zero or below, which meant that meagre pay rises in the public sector were not being eroded by price increases.

The final straw which has triggered this wave of public sector strikes is the dramatic rise in inflation during the COVID-19 crisis and the subsequent war in Ukraine. When Vladimir Putin invaded the Ukraine in February 2022, private sector pay increased by 5.9 per cent, inflation by 6.2 per cent and public sector pay by 1.7 per cent.

Putting the wage-price spiral theory to the test

The evidence that the public sector has been severely squeezed for more than a decade does not, of course, deal with the argument that pay increases could set off a wage-price spiral. However, the data in the graph does not support this idea. The correlation between public sector wage increases and inflation is negligible and not statistically significant (r = 0.04). This means that public sector pay is unrelated to inflation.

Interestingly, the same is not true for private sector pay. In this case, the correlation is weak but statistically significant (r=0.22), indicating that private sector pay contributes to inflation, but it is weak largely because price rises are primarily driven by supply shortages at present, rather than pay.

Private sector pay contributes to inflation, but it is weak largely because price rises are primarily driven by supply shortages at present, rather than pay.

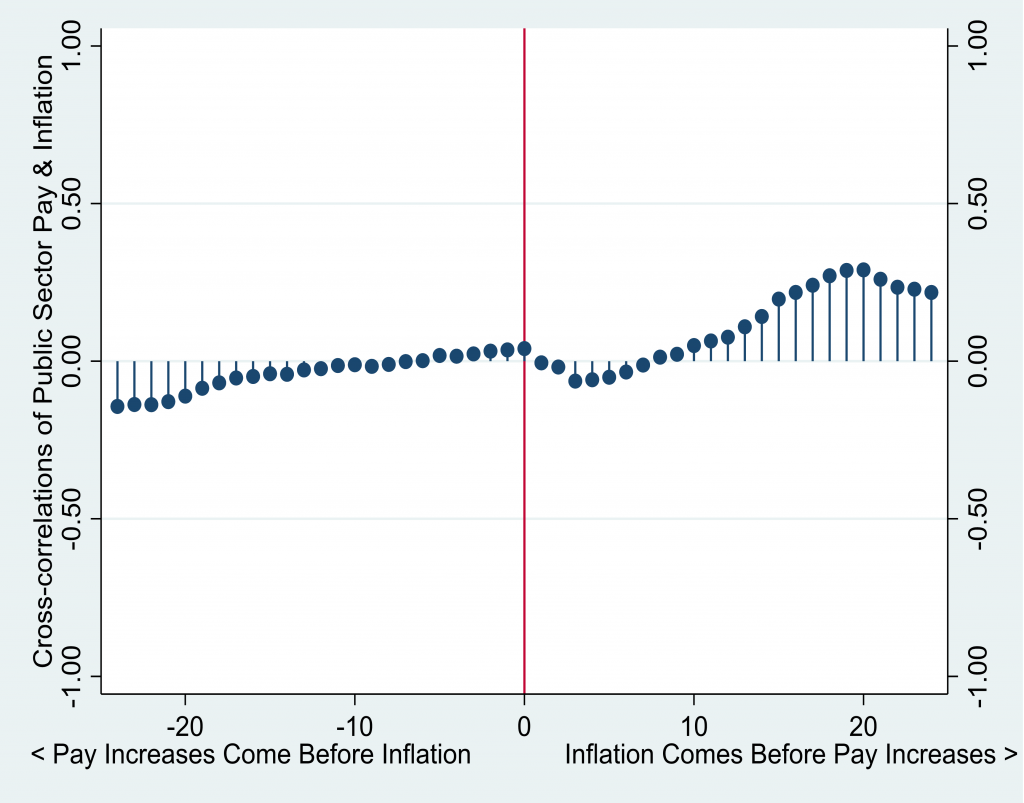

There is a problem with this analysis, however, namely that pay increases and inflation are unlikely to occur at the same time. There are always lags in the relationship between the two, posing the question: do pay rises in the public sector set off inflation in the months after they occur, or is it the other way round?

This idea is tested in the figure below, which examines correlations between public sector pay and inflation over time. The left-hand side of the figure shows the effects of past public sector pay increases on current inflation and on the right-hand side the effects of past inflation on current public sector pay. This is examined over a period of 24 months, and it shows that the effect of pay rises on inflation is negligible, whereas the effect of inflation on pay rises is substantial. The latter kicks in after a period of about a year.

Public sector workers are striking in response to inflation but there is no evidence that their wage increases are producing inflation. In effect, the wage-price spiral does not exist for public sector pay. A key reason for this is that the public sector labour force makes up only 17 per cent of the total work force, meaning that it has much less of an impact on the economy than the private sector.

The upshot of all this is that public sector workers are being penalised by reductions in their pay for reasons that do not bear up to scrutiny. Public sector pay increases do not translate into higher inflation.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Hossam el-Hamalawy, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)