In this post, Anna Valero assesses Labour’s key policies for raising productivity, the main problem facing the UK economy. She finds that claims that the party is “anti-business” are exaggerated; on the whole Labour appear serious about addressing the productivity challenge and the party’s certainty in terms of staying in the EU is good for business.

In this post, Anna Valero assesses Labour’s key policies for raising productivity, the main problem facing the UK economy. She finds that claims that the party is “anti-business” are exaggerated; on the whole Labour appear serious about addressing the productivity challenge and the party’s certainty in terms of staying in the EU is good for business.

In the run up to the general election, Labour have been accused of being “anti-business”. This has stemmed from Ed Miliband’s attempts to crack down on what he terms “predators”, while supporting the “producers”. Business leaders, keen to understand the implications of this, have been concerned about where the line would be drawn. Many fear increased intervention in markets which have become increasingly free since the 1970s. I argue that far from being anti-business, Labour’s manifesto for business takes a pro-business stance on two of the key issues facing the UK businesses: low and stagnant productivity, and the threat of “Brexit” which would lead to an immediate loss to GDP and longer term impacts on productivity growth.

Productivity

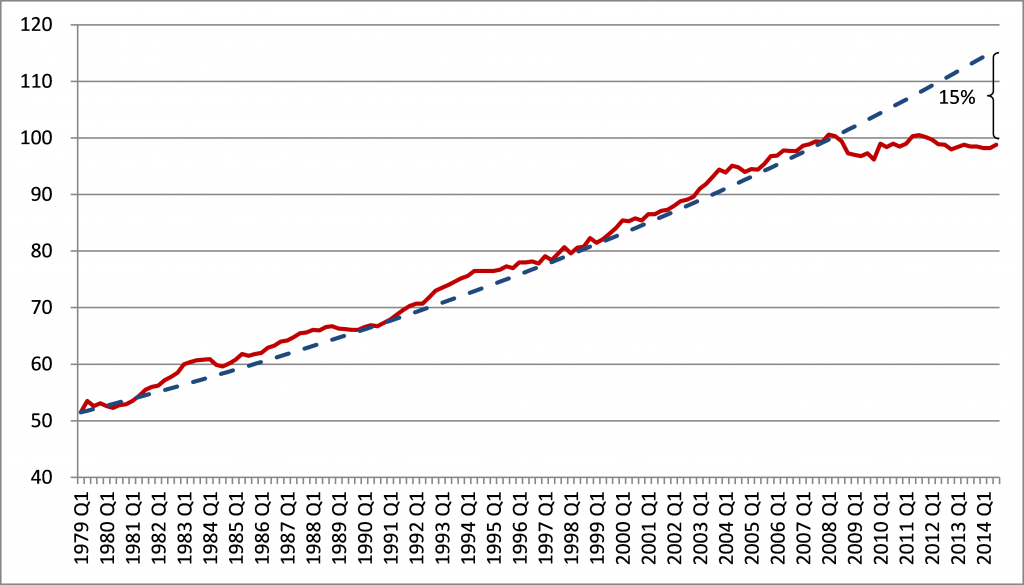

UK productivity levels have been lagging against our competitors for decades. As shown in the CEP election analysis on Productivity and Business Policies, currently, GDP per hour is 30 per cent below France, Germany and the US. The long term gap with other countries has been attributed to chronic underinvestment in innovation, infrastructure and skills (especially mid-level skills). The productivity gap has of course been exacerbated by the “productivity puzzle” – the especially poor performance of productivity since the financial crisis which so far, no one can fully explain. Today output per hour is about 15 per cent below where it would have been if the pre-2008 trend had continued (see Figure 1). Lower capital-labour ratios, and dislocation in the banking sector (which prevents innovative firms accessing finance) appear to be important factors for understanding this.

Figure 1: UK productivity growth – GDP per hour worked, 1979 Q1 to 2014 Q3

Source: Whole Economy GDP per hour worked, seasonally adjusted (2011=100). ONS Statistical Bulletin, Labour Productivity, Q3 2014, downloaded 6 February 2015.

Note: Predicted value after 2008 Q2 is the dashed line calculated assuming a historical average growth of 2.3% per annum (the average over the period 1979 Q1 to 2008 Q2).

Key to addressing these challenges is establishing a long-term framework for productivity and innovation, giving businesses certainty over government policies in these areas. Labour have highlighted this need and are promising a number of measures that could potentially be valuable. What follows is a summary and assessment of some of Labour’s key policies for raising productivity.

Promoting long-termism in business: taxes and governance

A long term outlook is necessary for investment in R&D, the fruits of which are uncertain and may be a long way off. Labour would examine the case for removing the debt bias in UK corporate tax, in favour of incentives for equity finance (which is more conducive to risky, but potentially rewarding projects). A number of adjustments to corporate governance rules could also promote a long-term outlook in business by making it harder to make decisions for short term gain. In particular, new duties for institutional investors to prioritise the long-term growth of the companies they invest in, and strengthening the role of long term investors in takeover situations.

While Labour do tend to favour higher corporate tax rates (and have indicated they would reverse the cut to 20 per cent announced by the Conservatives), they would keep the main rate at the lowest in the G7. But taking a more holistic view, cuts to business rates have been promised, and examining capital allowances (which are ungenerous by international standards) has been hinted at.

Support for small firms

A key bottleneck in the UK is a lack of finance for small, innovative firms. Pro-competition reforms in the banking sector under the coalition government have so far delivered limited results. Moreover, already in existence are a plethora of initiatives aimed at providing finance, information and expertise to small businesses. While these are in principle valuable, there are few robust evaluations of their impacts. Given the large sums involved, and the continued problems faced by small businesses, it would be useful for policymakers to work with researchers to implement controlled policy experiments to allow better informed policy making in the future.

Labour pledges to establish a “British Investment Bank”, strengthening the British Business Bank already in existence, with a network of regional banks. Borrowing the idea from the United States, Labour would also establish a new Small Business Administration which would increase small business representation in policy making and coordinate government activities to support small businesses. In addition, Labour would go further on pro-competition reforms in retail banking: with a new market share test for the banks and at least two new challenger banks. Elsewhere, Labour have also indicated that they would require full structural separation of retail and investment banking (going beyond the current internal separation required by the coalition).

Government funding for R&D

Labour state that they would introduce a new long term funding and policy framework for science and innovation. This is welcome, but more specifics would be useful here. In particular, the science budget has been declining in real terms (the coalition government has ring fenced it only in nominal terms). Furthermore, as a proportion of GDP, government spending on R&D is lower than other countries and has been declining. The hope is that the long-term framework would involve a realisation of the importance of doing more.

Infrastructure and Skills

An efficient infrastructure base and a plentiful supply of skills are crucial for productive businesses. A core recommendation from the 2013 LSE Growth Commission was to create structures for long-term infrastructure planning. In this vein, Labour would establish an independent National Infrastructure Commission. On skills, Labour would remove university students from the Government’s net migration target which should help address skill shortages reported by some businesses. A long-standing skill gap in the UK is at the mid-level. Labour are promising to improve basic skills (ensuring all young people study English and Maths to 18), and strengthen vocational qualifications. Key to the latter is designing qualifications and apprenticeships to genuinely add value to firms.

Economic regulation

Labour would overturn aspects of the regulatory system where there are concerns over the effectiveness of competition. They would freeze gas and electricity bills until 2017 and introduce a tougher regulation regime so that if wholesale prices fall and this is not passed on fairly to consumers, the regulator would have the power to cut prices. There is nothing wrong in principle with delegating extra power to regulators, but ad hoc fixing of prices by ministers is undesirable. It undermines the principle of independent regulation. The much bigger problem is the security of supply of energy as UK generating capacity is running dangerously low. The investment required to address this issue may require price rises in the future.

Brexit

Leaving the EU would be a disaster for UK exporters, since the EU is the UK’s most important trade partner. Analysis at the CEP has shown that Brexit would reduce GDP by between 1.1 per cent and 3.1 per cent due to lower trade alone. These losses would probably double due to dynamic effects on innovation and loss of easy access to future trade agreements, dampening productivity growth. Clearly the risk of lower productivity growth in the future is even more of a concern given our current performance discussed above. Factoring in these costs could lead to a loss in GDP comparable to that suffered by the UK in 2008-09 following the financial crisis. Moreover, there are additional costs that are harder to estimate – related to FDI, immigration and economic regulation. By removing the threat of exit following a referendum, Labour are giving businesses peace of mind in this area.

Conclusions

On the whole, Labour appear serious about addressing the productivity challenge. The focus on long-termism indicates this. Moreover, Labour’s certainty in terms of staying in the EU is good for business. In general the policies aimed at “unfair business practices” (such as the energy companies with market power, banks that are too big to fail, or tax avoiders) may not be popular with the businesses or individuals targeted, but should have mainly positive effects for small businesses. Claims that Labour are “anti-business” are exaggerated.

This article draws on the CEP’s 2015 Election Analysis on business and productivity policies and on leaving the EU.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Anna Valero is in her fourth year of the LSE MRes/PhD in Economics, and works on the Productivity and Innovation programme. Her work is focused on firm organisation and workforce skills, and their effects on productivity and innovation.

Anna Valero is in her fourth year of the LSE MRes/PhD in Economics, and works on the Productivity and Innovation programme. Her work is focused on firm organisation and workforce skills, and their effects on productivity and innovation.

1 Comments