UK productivity has been declining since the onset of the financial crisis, and today the gap with G7 nations is at its widest since 1992. João Paulo Pessoa, Anna Valero and John Van Reenen of the Centre for Economic Performance argue that underinvestment is key to understanding this. The recovery so far seems unbalanced; policymakers must focus on raising productivity to prevent it fizzling out.

UK productivity has been declining since the onset of the financial crisis, and today the gap with G7 nations is at its widest since 1992. João Paulo Pessoa, Anna Valero and John Van Reenen of the Centre for Economic Performance argue that underinvestment is key to understanding this. The recovery so far seems unbalanced; policymakers must focus on raising productivity to prevent it fizzling out.

The latest data from the ONS show that the UK’s productivity gap with other G7 nations is at its widest since 1992. This bad news comes against the backdrop of increased optimism as the economy seems finally to have returned to growth. Unfortunately, this growth seems to be generated by Britain’s usual suspects: consumer spending and a booming housing market (stoked by government subsidies like Help To Buy) rather than from exports and investment. The danger is that a recovery without underlying productivity growth is unsustainable.

Is the modicum of good news a vindication of the Chancellor’s austerity policies? Au contraire, George. The recovery (the slowest on record for the UK) has been in spite of, rather than because of, such policies. What is needed is renewed focus on raising productivity. Business investment is a crucial ingredient, and the government can do more to support this.

Illuminating the productivity puzzle?

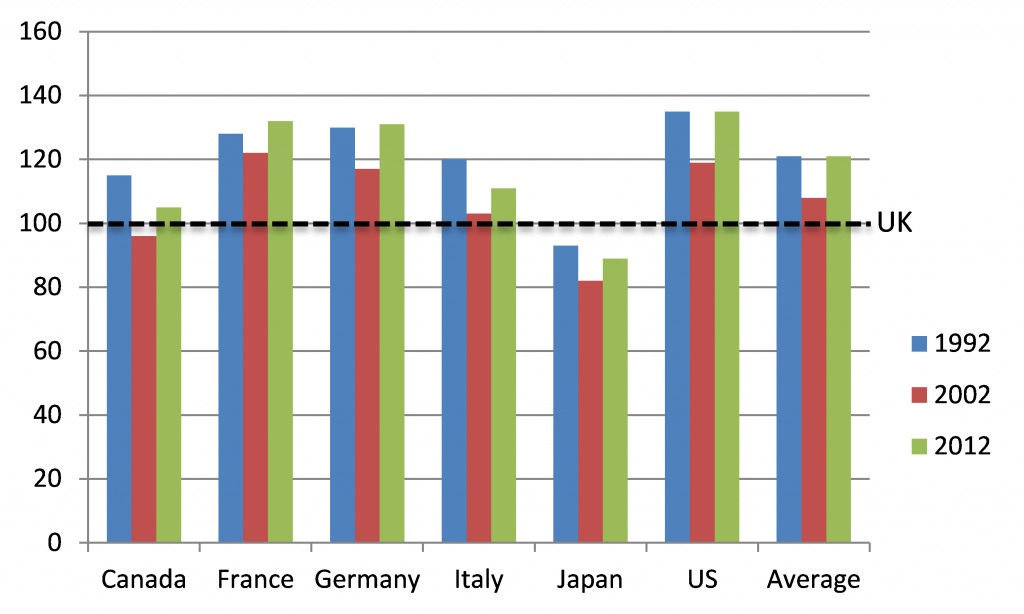

The latest ONS figures show that in 2012 labour productivity as measured by output per hour was 21% below the G7 average (Figure 1) – the widest gap for 20 years. In output per worker terms, the gap was 25%. Moreover, output per hour in 2012 was 3% lower than in 2007, a full 16% below the level it would have been on long-term pre-2007 trends continued. This lacklustre productivity performance since the financial crisis has been dubbed the “Productivity Puzzle” because such a fall has been unprecedented in post war UK history.

Figure 1: Output per Hour Worked, G7 Countries (UK=100)

Notes: Current price GDP per hour worked from ONS data, release date February 2014. Average refers to G7 average, excluding UK.

For many “supply side pessimists”, this indicates a large and permanent loss to productivity. According to this view output is very close to potential and so monetary and fiscal policy must be tightened.

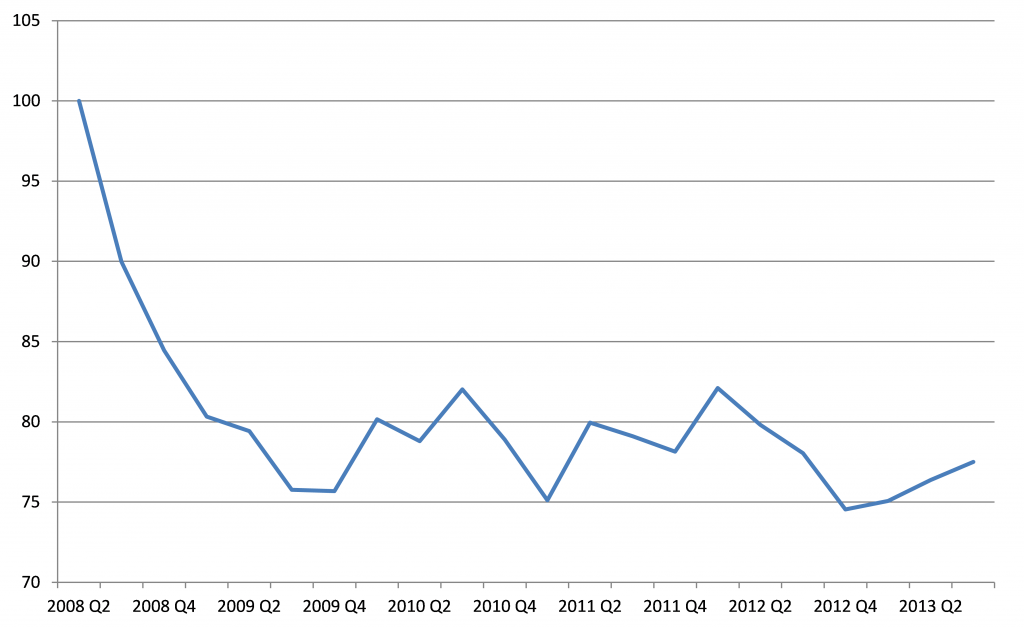

The flipside of the puzzle of low productivity is a jobs conundrum. Given that GDP growth has been so poor, it is remarkable that unemployment is not higher. Central to understanding this is the fact that UK real wages are far more flexible than in past recessions due to weakened union power and welfare reforms. In response to low demand, real wages have fallen by 8% since Lehman’s collapse (based on data to October 2013). This has helped keep labour costs low for employees and sustained higher employment. However, low wages and rising costs of capital due to banking dislocation have deterred business investment, as has high uncertainty and the disastrous decision to slash of public investment by half. Figure 2 shows how real investment has collapsed since 2008.

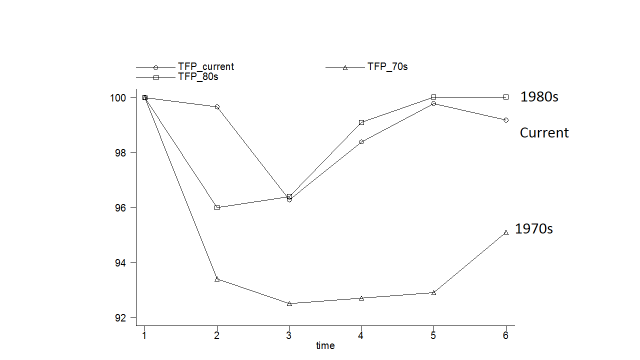

Lower investment can depress the amount of capital per worker and so will reduce labour productivity. Less machines per employee means less output per employee. This is not a fundamental loss of efficiency – as demand improves and credit markets return to normal productivity should rebound. A close inspection of the data, reveals that once we correct labour productivity for these changes to get a measure of efficiency (sometimes called Total Factor Productivity or TFP), things are not so different this time round from other severe recessions (see Figure 3).

Other factors may also matter for the recent productivity puzzle such as misallocation of capital due to forbearance, mis-measurement of intangible capital and labour quality deterioration. But the underutilised resources caused by low demand and “capital shallowing” due to changes in the prices of labour and capital seems to explain a large chunk of the mystery.

The LSE Growth Commission has shown that there is underlying strength in the UK economy built up since the early 1980s when the UK reversed a century of relative economic decline. Productivity growth in the three decades leading up to the crisis was broad based with finance only contributing around a tenth of the improvement. Much of these improvements were due to policy reforms strengthening competition in product and labour markets, the benefits of which are unlikely to suddenly evaporate.

Figure 2: The collapse of real investment, 2008-2012 (2008 Q2=100). Investment defined as total (cross sector) gross fixed capital formation, chained volume measures, seasonally adjusted.

Notes: ONS data, release date December 2013.

Figure 3: Change in Total Factor Productivity across UK recessions

Notes: 1970s and 1980s derived from EU KLEMS data. 1970s recession is 1973-1978; 1980s recession is 1979-1984; Current is 2007-2012. 2000s authors’ estimates in Pessoa and Van Reenen (2013)

Unbalanced recovery

So the story of the supply side pessimists doesn’t stack up. If the demand side is important, then excessive austerity may have led to a slower recovery with the risk of permanent structural damage through “hysteresis” effects. Regardless of how we may quantify this lost growth (e.g. the Jorda and Taylor estimates), the important fact is that we could have done a lot better.

Business investment has stayed flat: the latest ONS data show that while business investment rose 2% in Q3 2013 compared to the previous quarter – it was 5.3% lower than Q3 2012.

Distortions with our financial sector still remain – lending to companies has not picked up, despite favourable credit conditions and lower funding costs for banks. Banks are attempting to re-build their balance sheets which has made them reluctant to lend, and enforce covenants over bad loans. The result: insufficient capital is flowing to high growth potential enterprises.

Long term, pro-growth policies

Most of the recent falls in productivity are due to temporary factors such as weak demand and financial sector turmoil. Poor fiscal policy and a failure to adequately address banking problems has exacerbated these problems, but cannot hold back the rebound indefinitely.

This should not make us complacent over productivity. There was a significant gap with our peers even prior to the crisis (as can be seen in Figure 1) which held back living standards. We need to focus on strengthening the foundations of the UK through long-run investments in infrastructure, skills and innovation along the lines set out by the LSE Growth Commission. Cutting public investment in a depression is bad short-term macro policy as well as foolish long-term growth policy. In political terms it made sense – cuts in investment are bruises that are not usually seen in public. That is, until many years later or, in the case of flood defences, when the water starts coming down.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

João Paulo Pessoa is an occasional research assistant in CEP’s productivity and innovation programme. He started his MRes/PhD in economics at LSE in 2009. Before coming to LSE he worked as a financial products analyst for three years at BBM Bank.

João Paulo Pessoa is an occasional research assistant in CEP’s productivity and innovation programme. He started his MRes/PhD in economics at LSE in 2009. Before coming to LSE he worked as a financial products analyst for three years at BBM Bank.

Anna Valero is in her third year of the LSE MRes/PhD in Economics, and works on the Productivity and Innovation programme. Her main interests are in applied industrial organisation and labour economics. Previously, Anna was a Manager at Deloitte’s Economic Consulting practice where she worked on a number of projects on regulatory, competition and strategic economics across sectors, but specialising in utilities, public sector and media.

Anna Valero is in her third year of the LSE MRes/PhD in Economics, and works on the Productivity and Innovation programme. Her main interests are in applied industrial organisation and labour economics. Previously, Anna was a Manager at Deloitte’s Economic Consulting practice where she worked on a number of projects on regulatory, competition and strategic economics across sectors, but specialising in utilities, public sector and media.

John Van Reenen is Professor in the Department of Economics London School of Economics and the Director Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics. He is also Fellow of the British Academy, Econometric Society and the Society of Labour Economists.

John Van Reenen is Professor in the Department of Economics London School of Economics and the Director Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics. He is also Fellow of the British Academy, Econometric Society and the Society of Labour Economists.

There is definitely a problem in the UK around management. And what management means.

Companies teach managers how to firefight. Which is great. So we have a country full of people who are good at driving firetrucks but not at improving anything to any real degree.

We then wring our hands over why we are not as productive, making the major mistake of management, looking at the outcome and not the people or work process that generates the outcome.

Well, this is a fascinating piece, especially when viewed on the other side of the Atlantic, where productivity was restored, but wage growth was not. I pose the central question here in American: for the three dominant decades of neoliberalism which preached that worker’s wages and their share of the pie could only improve as productivity improves, why now, when it has, has the factoring in of productivity in the calculation of the minimum wage been nearly eliminated from discussion, even on the left?

Here’s my more formal take on that:

MAKING MILLARD TYDINGS PROUD: ECONOMIC “JUSTICE” in ANNAPOLIS

February 27, 2014

Dear Citizens and Elected Officials:

As centrist Democrats fret about the possibility of a genuine left populism rising to challenge them, inside or outside the party, and members of the very top rungs of the financial elite express their feelings of persecution in national media outlets in very unsavory terms, I’ve been trying to follow the minimum wage debate here in Maryland, my home state for the past nine years. I will quickly confess my self interest in this matter, having written about the political economy extensively over the past seven years, and also from the more recent fact that I labor at that convenient borderline of 30 hours per week at $8.75 per hour for a Fortune 100 company. And that princely sum comes after 18 months on the job, winning an 11 cent per hour raise after my first year. Yes, I’m on my way back into the “Middle Class,” climbing the ladder of mobility rung by rung, cent by cent.

When I first began writing about the minimum wage two years ago, I noticed that the entire discussion, even among progressives, which is where it started, was only about making up for losses to inflation since that golden baseline year for labor, 1968, But wait a minute, I objected: whatever happened to the discussion of productivity, which was absolutely and obsessively insisted upon by all the right people in the economics profession and corporate management ever since the mid-1970’s. There could be only a downward escalator, or at best wage stagnation, unless productivity increased. Well, I said, here we are in 2014 after the microchip- computer, Internet and IT “revolution,” the marvels of American invention, the unravelling of the human genome…biotech!…and the “evolution” of the lean and networked international corporation and supply chain…as Thomas Frank wrote in 2000, we would all be in “One Market Under God”…and oh yes, after all those debt fueled corporate mergers which had, as we all know by wrote, only one motivation: to make business more …productive… by the wholesale slaughter – layoffs – of those bloated and despised – unproductive! – middle managers. So there are costs to “creative destruction,” high human costs and many other costs that Americans cannot squarely look in the eye.

Productivity there was, no doubt; now where was labor’s missing share, I asked Dean Baker and at the time I asked him he was just about ready to supply some numbers, the most prominent economist to courageously venture into this logical line of reasoning but explosive ideological minefield…really just picking up where our social betters had led us during the past three decades.

So economist Baker used two sets of conservative assumptions and came out with two numbers. Labor’s missing share of productivity would put a new and fair national minimum wage at between $16 and $21 dollars per hour – phased in gradually of course; no responsible advocate for these numbers could insist upon rapid implementation…certainly it could not be done the way millions were riffed from middle management in the 1990’s…here today, gone tomorrow. Separation stipend and clear out by 4:30. What color is your parachute? Since that time, other progressive economists have piled in, and readers can do much worse than read the New York Times lead editorial from February 8th, here at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/09/opinion/sunday/the-case-for-a-higher-minimum-wage.html?_r=0 which manages to reveal more than most of the liberal lobbying material reamed out by progressives.

The Times points out that “even a boost to $10.10 an hour by 2016 (also adjusted to 2013 dollars) would lift the minimum to just above its real value in 1968. So while it is better than no increase, it is hardly a raise.” The Times makes a case for $11.00 per hour while comparing today’s minimum to the “average” wage for non-supervisory production workers in the private sector. Then comes the shocker: “The problem is that the average wage, recently $20.39 an hour, has also stagnated over the past several decades, despite higher overall education levels for typical workers and despite big increases in labor productivity…If the average wage had kept pace with those productivity gains, it would be about $36 an hour today, and the minimum wage, at half the average, would be about $18.00.”

Well thank you, New York Times. I didn’t expect you to be filling me in on what Centrist and even Progressive Democrats have decided on their own to leave out, skipping the productivity considerations and focusing only on links to lost inflation factors and, of course, silently factoring in the unspoken political “realism.’ These tactics and decision making processes leave me suspicious that this is not going to be a “first step,” followed by many others to bring wages and the missing productivity gains into alignment with historical reality – and economic justice. No, I suspect the Democrats are going to try to do this $10.10 and then it won’t come up again for a decade and productivity can, well, be tossed into the dustbin of history. Unless management finds it again a convenient discussion to have.

This is not an argument to abandon the current minimum wage bills in Maryland(HB 295, SB 331) ,or nationally, please don’t misunderstand me. Millions of workers at the very bottom, at the bare minimum wage, can use any help they can get. But please, please, don’t delude yourself, Democrats, or us, that this figure is going to lift anyone out of poverty, where here in Montgomery County Maryland the County Council itself said a living wage for us was $17.00 per hour but only got a bill passed to get to $11.50 per hour by 2017, and having to give up the linkage to inflation to get that. And I didn’t detect much enthusiasm among the other council members for Councilman Marc Elrich’s bold and skillful tactics in getting it passed. And remember, even many more millions of the working poor are not at the bare minimum, they are earning somewhere between $8.00-$10.00 per hour – that is how EPI reached its astonishing figure of 28 million Americans working for $9.89 per hour or less.

President Obama, I don’t think the nation or your proposed policies include anything close to 28 million, or 14 million even, “ladders of opportunity.” So maybe we ought to put aside illusions of mass mobility and just make the pay and working conditions there “in place,” more humane.

But I am not finished. I have to be true to my own efforts in writing over the past seven years and the ignored and spurned work of many progressive economists like James Galbraith, L. Randall Wray, Thomas Palley and yes even Paul Krugman, who started out arguing for an array of greater stimulus programs, higher wages, direct governmental job creation programs built on infrastructure rehabilitation and expansion, combatting global warming, environmental restoration…and so on…a full array of programs that year by year were stripped off, pared down, whittled away by both the arrogance and intransigence of the Republican Right and the Democratic Centrist collaboration in neoliberal ideology…when the human needs were staring us all right in the face, screaming silently as people were tortured through the foreclosure process, thrown out of work or written off as too old or without the proper skills. So don’t try to convince me or anyone else that $10.10 is sufficient, adequate or some great humanitarian effort…it’s almost a bare skeleton…no not even that, just one bone from a fully human policy response to the great financial crisis.

So now let us pick up the scent on the trail of Maryland’s pursuit of $10.10 per hour, backed by all those national opinion polls as well, and the Maryland Governor, Martin O’Malley, a contender for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016. In testimony given before a Maryland Senate Committee on February 17th, the Governor said this figure is actually “pretty modest.” Yes Governor, it certainly is; that’s the result of leaving out all labor’s share of the missing productivity gains. And ignoring most of what the New Deal did in the 1930’s to create full employment, however incomplete its success, and despite the opposition of Maryland’s famous, or infamous, Senator Millard Tydings, who opposed FDR’s New Deal.

But then, after the 17th, the Maryland trail goes cold. Even some Montgomery County Councilmembers are arguing that maybe it should just be left to Maryland counties; doubtless other legislators none too favorably disposed but reluctant to say it in public, will now argue that Maryland should wait to see if the federal government passes a $10.10 or $9.00 per hour bill. For one has to admit American federalism – that is, what layer of government will or should act – that it is not only the famous laboratory of democracy, but also a great stalling ground for insincere politicians. I kept Googling and looking at my incoming Emails after this initial hearing, and the trail of the bill was dying out; not even its advocacy groups were reporting anything. And then, growing even more curious, I found this alarming piece from the Executive Director of Progressive Maryland (Kate Planco Waybright) at David Moon’s Maryland Juice website:

http://www.marylandjuice.com/2014/02/guest-post-progressive-maryland-sounds.html

I was incredulous at first; then it began to make sense: the minimum wage bill was stalling, and in its place, accelerating – was a bill to change Maryland’s estate tax to mirror the one passed by the Republican Right a few years ago, changing Maryland’s threshold from one million to match the higher federal one – in year-by- year increments of tax break generosity.

And then we have the sponsors of these estate tax breaks bills, SB-602 and HB-739: Senate President Mike Miller, true salt of the earth, friend of the working man, friend of nature too, no doubt and no surprise…but his often times opponent, House Speaker Michael Busch…et tu Busch? , who always was spoken of as many steps to the left of Miller…or was it just several steps…or a baby step…and then the other names supporting it: Senators Jennie Forehand, Karen Montgomery, Brian Feldman…and on the House of Delegates side: Luiz Simmons, Jim Gilchrist, Anne Kaiser…Ana Sol Gutierrez… no, no this can’t be true, can it? But apparently it is. And I noticed an interesting pattern. Most of these surprising co-sponsors of additional tax breaks for the wealthy – and the loss of revenue for Maryland, because that’s what the state’s top legislative analyst projects – are also supporters of the minimum wage bill. If you can ignore 30 years of national economic history, I guess you could call that “fair and balanced” legislating.

Is this a coincidence, or are the Democrats signaling that this minor and in fact harmless gesture to their long forgotten New Deal base, the working class, is so threatening during this period of rising storm clouds on the left – are these Centrists and yes even progressives- listening to Ralph Nader, Gar Alperovitz and Chris Hedges on the Baltimore based RealNews Network, as I am? Are they so afraid of this minor humanitarian gesture to the working poor (and the unemployed can go and eat dandelions in a couple of months, can’t they?) that they have to counter-balance it with tax relief to the wealthiest among us?

Well citizens, I hope I am very, very wrong, but I have already gone out on a limb and predicted no minimum wage bill for Maryland, and passage of estate tax relief for the destitute in Potomac, with Maryland proudly living up to its new ranking as having the highest per capita ratio of millionaires in the nation. Please tell me I am wrong, because if it is true, then I fear for our country because this minimum gesture is just one small step in making up for thirty years of outrageous policy and unfairness towards the majority of our citizens in matters of economic justice – and decency’

Disappointing that inequalities do not figure more in this otherwise good piece. Where the ‘squeezed middle’ of the middle class professionals and working class/blue collar workforce cooperate in productivity enhancing measures and see that they are getting a less and less commensurate share of the additional GDP created, this may negatively impact on workplace and marketplace behaviours. More, significantly the ever-increasing concentration of income, assets and wealth into the tiny minority elites means that potential expenditure and investment activity in and among the broad workforce does not happen. The working class/blue collar workforce was the first to take the hit in this way. The huge and exponential application of technology to services as well as production meant that the professional middle classes have followed. Evidence has emerged for some time now that that has been the scenario in the USA for some decades. There seems good reason to assume that the same trends have been also applying in the UK (as usual after a lag behind the USA). The UK and USA stand as among the most grossly (and increasingly) unequal advanced economies in terms of unearned and unmerited wealth and income.