Yesterday saw the Chancellor’s autumn statement. Tony Dolphin argues that the measures announced in this ‘mini-budget’ are not a real plan for growth. If increased demand is not generated – and only the government is in a position to do this – then unemployment and public sector borrowing will continue to rise in excess of previous predictions.

Yesterday saw the Chancellor’s autumn statement. Tony Dolphin argues that the measures announced in this ‘mini-budget’ are not a real plan for growth. If increased demand is not generated – and only the government is in a position to do this – then unemployment and public sector borrowing will continue to rise in excess of previous predictions.

Eighteen months ago, George Osborne set out the Coalition government’s approach to economic policy. Deficit reduction was the priority for government. If it was delivered, he argued, growth and new jobs would be generated in the private sector. The government could help the private sector only by getting out of its way: by cutting corporation tax rates and axing regulations.

With the economy having expanded by just 0.5 per cent over the last year and unemployment at its highest rate since 1996, this approach is no longer sustainable politically. The government has to be seen to be doing something more positive to support the economy, hence the raft of announcements – on infrastructure, youth unemployment, housing and credit easing – that preceded the autumn statement.

This change of heart is welcome and the new measures are well-targeted at some of the current weaknesses in the UK economy. However, the chancellor has stuck rigidly to his Plan A for deficit reduction. Rather than increase government spending (or cut taxes) to tackle the economy’s problems, he has had to find alternative solutions. In some cases, this means he is saving money in one place to spend more in another; in others, the solutions will only be delivered slowly. As a result, he is not tackling directly the most urgent problem facing the economy: a shortage of aggregate demand.

The latest economic indicators suggest private sector spending is unlikely to expand in coming months, leaving the economy teetering on the brink of a return to recession and unemployment likely to increase further. The OECD’s latest forecasts, released just one day before the autumn statement, show the UK economy falling back into recession, with real GDP contracting at an annual rate of 0.1 per cent in the final quarter of 2011 and of 0.6 per cent in the first quarter of 2012.

Reduced growth

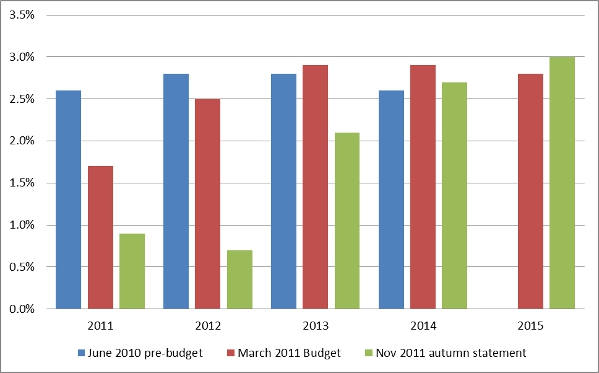

The autumn statement is accompanied by the latest forecasts from the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). These are unremitting bad news for the chancellor. As Figure 1 shows, growth is expected to be significantly lower than previously forecast in both 2011 and 2012. The economy is not forecast to grow at all between Q3 2011 and Q1 2012, coming as close as it is possible to get to falling into recession without actually doing so.

Figure 1 – OBR Real GDP growth forecasts

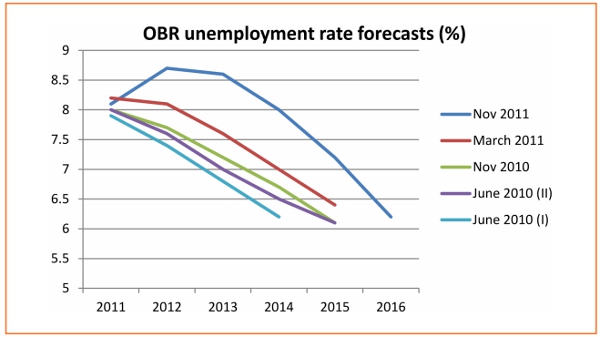

On the basis of the latest forecasts, output will not return to its pre-recession peak until the first quarter of 2014, making this the deepest recession and slowest recovery in the last 100 years. As a result, unemployment in 2013 will still be 8.6 per cent, compared to 5.2 per cent at the end of 2007. As Figure 2 shows, in 17 months, the forecast for unemployment in 2013 has increased from 6.8 per cent in the OBR’s first forecast, made ahead of the June 2010 budget, to 8.6 per cent.

Figure 2

A greater deficit than predicted

Weaker growth means that the outlook for the budget deficit has also deteriorated. Economists focus on two measures of the deficit – overall public sector net borrowing and the cyclically-adjusted current deficit – as well as on the overall level of debt. The chancellor has set himself fiscal objectives for two of these measures:

- To achieve a cyclically-adjusted current balance by the end of the rolling, five-year forecast period

- To have public sector net debt (as a percentage of GDP) falling by 2015/16.

At the time of the March 2011 budget, the OBR judged that he was on course to achieve both of the objectives one year early (that is, in 2014/15). Its latest forecasts show this is no longer the case. The cyclically-adjusted current balance only moves into surplus in 2016/17 and net debt starts to fall in 2015/16. The chancellor is only still on course to achieve his first objective because the end of the five-year period has been rolled forward from 2015/16.

There are two important implications of these forecasts. First, more deficit reduction will be required in the first two years of the next parliament. Previously, the chancellor had created a bit of room for a pre-election giveaway in March 2015; that has now disappeared. The next election, rather than being fought over how to spend the benefits of growth, will be fought over where spending should be cut, with implications for all parties.

Second, there is virtually no more room to manoeuvre on the debt rule. Any future upgrading of borrowing for 2015/16 – whether cyclical or structural – will have to be offset by discretionary fiscal tightening. This is very important. If the eurozone crisis deepens, leading the OBR to further downgrade its growth forecasts for 2012 and 2013 and to increase its borrowing forecasts over the next five years, then it will also be forecasting an increase in debt after 2014/15. Unless, the chancellor is prepared to relax his second rule, he will have to cut spending or increase taxes more than currently planned to get back on track. In other words, from here on fiscal policy will be pro-cyclical: weaker growth will lead to fiscal tightening.

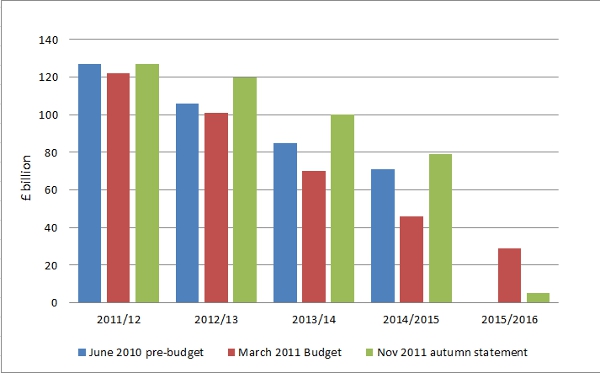

In aggregate, public sector net borrowing is expected to total £111 billion more over the five years 2011/12–2015/16 than was expected in March (see Figure 3). This makes the chancellor vulnerable to the accusation that not only is his plan not working in terms of supporting growth and reducing unemployment, it is not even working in terms of reducing government borrowing.

Figure 3 – Forecast public sector net borrowing

Bond markets

Throughout the last 18 months, the chancellor’s fiscal plans have been framed by the expected response of bond markets. His oft-expressed view is that not cutting the deficit as fast as he is doing would make the UK less attractive to bond investors, risk the UK’s AAA credit rating, and lead to higher interest rates. Events in parts of the eurozone and the current level of gilt yields in the UK – at around 2.25 per cent, close to their historical low – would appear to support his argument.

However, it is not so simple. Japan has a far higher level of public debt than the UK, and has done for many years, yet it has even lower bond yields. Bond yields are not determined by the size of a government’s deficit (or the level of its debt) alone. They also depend on the level of demand for bonds, the outlook for growth and inflation, the level of short-term interest rates, and the degree of risk aversion in financial markets. The fall in bond yields in the UK this year is largely the result of continual downgrades to the outlook for growth, resulting in delayed expectations of increases in short-term interest rates.

If the government had no deficit reduction plan, yields would undoubtedly be higher. If it had started with a plan that reduced the deficit more slowly – say over six years rather than four – yields would probably be little different from current levels now.

Announcements

The chancellor gave some details of how the new policy of credit easing would work. This scheme will underwrite £20 billion (potentially increasing to £40 billion) of bank lending to small and medium-sized businesses (those with a turnover of less than £50 million a year) in the UK. The basic idea is a good one: banks will be more willing to lend to small businesses, and at lower rates, if there is a government guarantee. If it works – and it does require the co-operation of the banks – this should ease the credit constraints facing the small business sector and allow it to expand and take on more employees than would otherwise be the case.

The prospect of higher fuel duties and train fares in the New Year has attracted much criticism in recent weeks, so the chancellor could be accused of pandering to public opinion by deciding to delay the fuel duty increase and moderate the rise in rail fares. He might counter that these measures are designed to ease the squeeze on working families – something his opponents have urged him to do. However, his case is weakened by the fact that these measures appear to have been funded, in part, by extra savings from working tax credits.

The increase in free childcare places for two-year-olds is a welcome move that will help some parents get back into the workforce sooner. It should be a first step towards a system of universal childcare for preschool children. The cut in aid spending is a consequence of the lower growth forecasts. The government still plans to increase spending to 0.7 per cent of GDP, but now that GDP is expected to be lower, this represents a smaller nominal amount – hence the cut.

A real plan for growth is needed

This was more like a mini-budget than an autumn statement. The likelihood that the OBR’s forecasts – and particularly its downgrading of the growth outlook – would dominate headlines following the autumn statement caused the government to preannounce a series of measures designed to support growth. The aim, no doubt, was to give the impression that the government had a ‘plan for growth’ as well as a ‘plan for deficit reduction’. However, it is not enough to agree a number of measures – even if some of them are welcome U-turns from the government’s previous position – and call them a ‘plan for growth’.

A real plan for growth should start by identifying what is needed for the economy to grow. In the medium term, that means increased supplies of capital, labour and land, and better ways of utilising them. But in the short term it means generating additional demand. With our main export market heading into recession and household and business confidence low, only the government is in a position to provide this extra demand. However, this would mean relaxing the pace of deficit reduction; that was a U-turn that the chancellor was not prepared to make on this occasion. It remains to be seen whether the chancellor will take the same approach if the growth outlook continues to worsen next year. On the current rules, any further increase in the borrowing forecasts – whatever its cause – will necessitate spending cuts or tax increases, otherwise debt will not be falling by 2015/16. Will the chancellor be prepared to tighten fiscal policy as the economy deteriorates? If the eurozone crisis escalates, we may find out in March.

This article is a shortened version of the IPPR briefing, George Osborne performs a U-turn, but not on the issue that matters.

Please read our comments policy before posting