Political science has very few ‘laws’, perhaps explaining why the discipline has so stubbornly clung onto Maurice Duverger’s famous claim that countries using first-past-the-post voting systems will always have two party politics. It is no exaggeration to say that this proposition still underpins whole fields of research. Yet Patrick Dunleavy explains that modern theory and better evidence now show that the alleged ‘Law’ has lost all credibility.

Political science has very few ‘laws’, perhaps explaining why the discipline has so stubbornly clung onto Maurice Duverger’s famous claim that countries using first-past-the-post voting systems will always have two party politics. It is no exaggeration to say that this proposition still underpins whole fields of research. Yet Patrick Dunleavy explains that modern theory and better evidence now show that the alleged ‘Law’ has lost all credibility.

All elections (indeed all competitions) have a horse race element in which most attention from the media, elites and voters themselves tends to focus on the top two contenders, as much in proportional representations contests as in British-style voting systems. Yet the most famous ‘law’ in political science, coined by Frenchman, Maurice Duverger in the early 1950s, holds that the operations of first-past-the-post voting system with single-member districts directly and strongly tends to cause two party politics.

So the USA, UK, India, Canada and other Westminster systems should all be two-party polities in this perspective, if not at the aggregate national level, at least at the level of contests in each local constituency. Modernized and made more operational by Gary Cox in an influential 1997 book, Making Votes Count, Duverger’s Law still has so many thousands of cites in political science literature that no practicable citations count is really feasible. (Google Scholar yields over 37,000 references, and Google Books nearly 9,000 more, but both cover mostly since the mid-1990s).

Duverger claimed that his effect operated in two ways. First, politicians know that a party can only ever win a seat by coming top in a local election district (or constituency) – that is, by winning the largest pile of votes (a plurality), whether or not the party has a local majority. So if you are not going to be in the top two parties locally, why stand? Nationally, what’s the point of coming second, third, or fourth in lots of seats without winning any – the traditional fate of liberals in the UK since the 1930s. As a result, third and fourth parties don’t stand, and if they do, they quickly die out.

Second, voters know that only the top two parties are contenders, so why ‘waste’ their one and only vote on supporting an also-ran party that is going to come in at a third, fourth or lower place? The pressure to make a difference pushes voters instead to back the top two and leave the rest to wither on the vine.

The USA

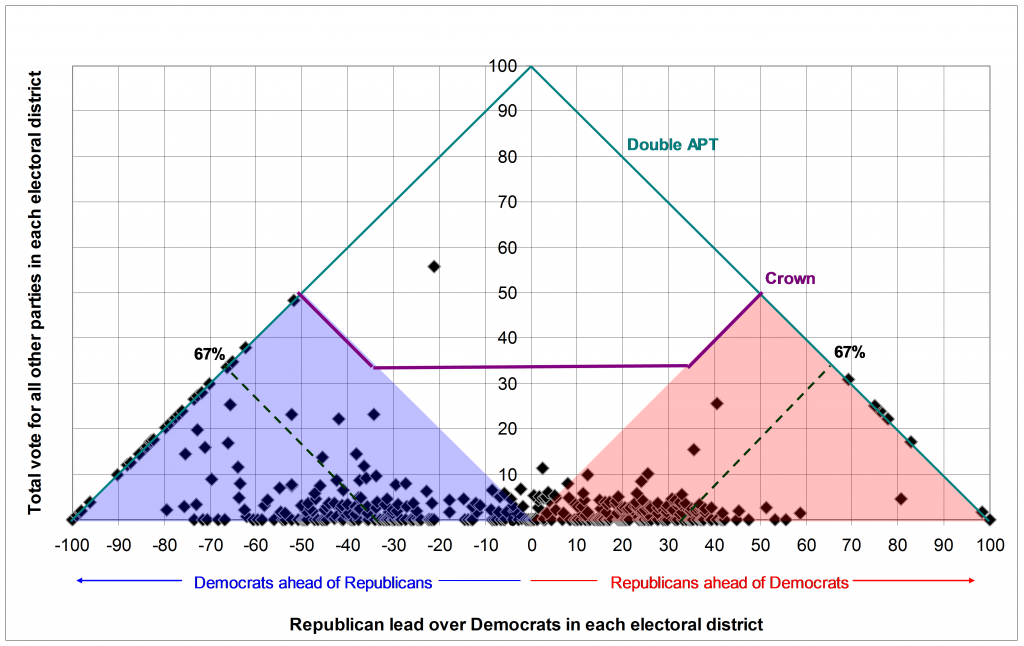

This logic still works in the USA, and my first chart shows how the resulting American party system looks. (This chart and both subsequent ones are drawn from joint work with Rekha Diwakar). Going down to the level of 450 seats in the House of Representatives, the bottom axis shows seats where Republicans are in the lead on the right hand side of the chart, and seats where Democrats lead on the left-hand side. The vertical axis shows the combined proportion of votes in each locality backing third, fourth or fifth parties.

Chart 1: District outcomes in the US House of Representatives, 2006

Source: Dunleavy and Diwakar, 2011.

Source: Dunleavy and Diwakar, 2011.

Duverger’s prediction is completely borne out here. All the seats are piled along the bottom axis, often with zero support for third parties in two-party only contests. When there is any degree of support for third and subsequent parties, it is almost always tiny or very minimal. The two coloured triangles show zones where one of the top two parties wins a clear majority (50% + 1) of local votes in the election district – the red zone being Republican seats and the blue zone being Democrat ones. Virtually all the 450 available seats in the House of Representatives lie in one or other of these coloured zones. Indeed in quite a large number of seats the leading party is piling up super-majority vote shares in the 70 to 90 per cent range.

The only odd seats with higher level of third party support actually occur not in the middle white areas (as one might expect) but in these high dominance areas. These outlier results do not genuinely mean high levels of third party voting however – instead they just reflect a local Republic dominance that is so complete that no Democrat candidate will stand and lose their money doing so, and vice versa in the Democrat majority areas. Here voters denied a major party choice plump for the closest they can get to a viable opponent – for instance, rightwing voters denied a Republican candidate to support will back the Libertarian. So even these cases do not undermine Duverger, but instead underline one-party dominance areas.

But the fact that one country appears to offer strong support to Duverger’s Law is not in itself very helpful, since the USA has many other features that might conduce to the same effect – including a Presidential system, the absence of socialism, a political plutocracy, an absence of much limits on campaign spending and political advertising, etc.

Two other large FPTP countries

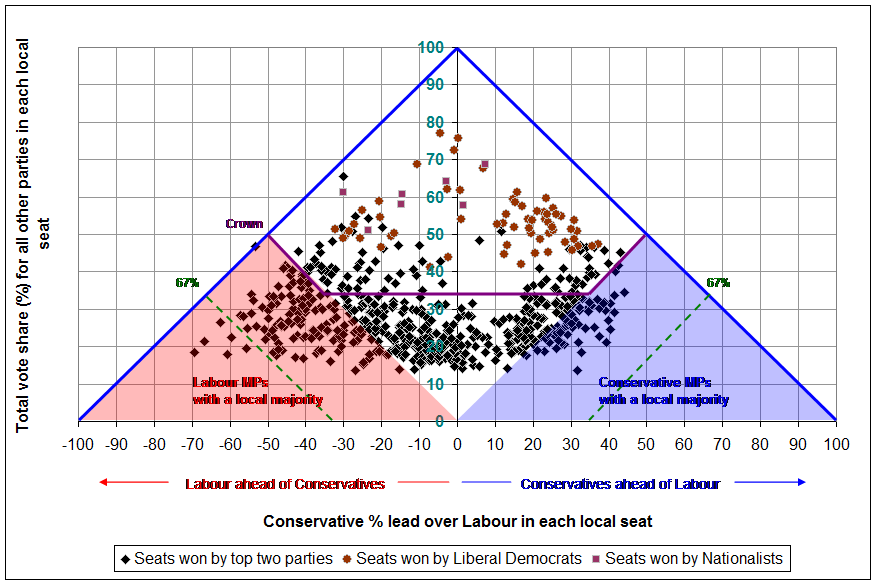

So the question that needs answering is whether this same pattern occurs at the local district level in all plurality rule voting systems, as Duverger deemed it would? My second chart shows the situation in Great Britain and it should be immediately obvious that the pattern here is completely different from America.

Chart 2: Constituency outcomes in the 2005 general election, Great Britain

Source: Dunleavy and Diwakar, 2011

Source: Dunleavy and Diwakar, 2011

Here no local contests at all produce results either on or even near the bottom axis of the chart. And very few lie within the shaded triangle areas for Conservative and Labour local majorities. There are almost no seats where any party gets more than two thirds of the vote. All these effects occur because the whole cluster of seats is lifted off the bottom axis, with more than 15 per cent of the available votes going to third, fourth and smaller parties in virtually every constituency across the country.

There is clearly still some two-party focusing going on in British elections, as there is any election. But in addition, of course, the upper part of the overall triangle here is thickly populated with seats where the Liberal Democrats, Scottish Nationalists and Welsh Nationalists have come first and won the constituency (shown as brown dots). So in every respect, this is a very different chart from that of the USA.

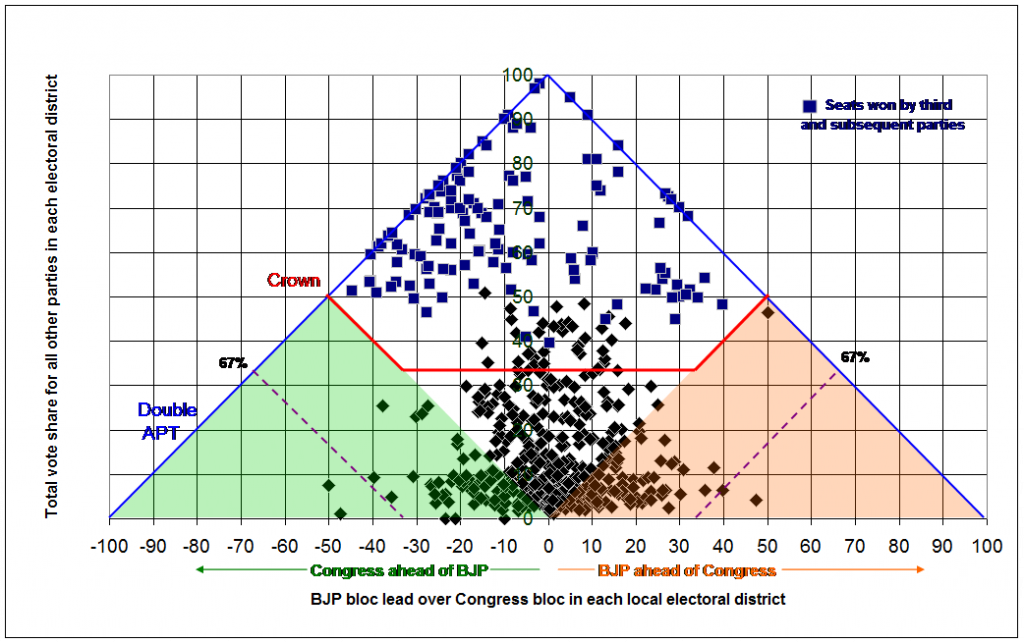

Let’s look now at the world’s largest plurality rule voting country, India, shown in my third chart. There the pattern is radically different again. Here there is quite a big bunching of seats close to the bottom axis, and some even on the axis itself. But even in this minority of seats, almost nowhere does any candidate get more than two thirds of votes. And seats in the areas where the two leading party blocs have local majorities are clearly a minority – the BJP being the orange shaded area and the Congress being the green. Even at the bottom of the chart, most of the seats lie in the middle white area where neither of the big party blocs has a local majority.

Chart 3: District outcomes in the Indian Lok Sabha elections in 2004

Source: Dunleavy and Diwakar, 2011

Source: Dunleavy and Diwakar, 2011

There is a second prominent feature of the India chart, namely the large ‘mushroom cloud’ of seats that surges up from the white areas at the bottom to the top of the overall triangle. The top zone here encompasses seats (shown as blue dots) where parties other than Congress or BJP win or dominate local voting, including the Communists and many different regional and local parties.

Facing facts, revising theories

Any physical scientist looking at these three charts could tell straight away that we are looking at three radically different systems. The idea that parties or voters are behaving in the same ways across them is deeply unlikely. The factors leading to perfect two party politics in the USA cannot be general to all plurality rule systems – they must instead be specific to the American political context. Incidentally perfect two-party systems like this are now found almost nowhere outside the USA, except for a few small Caribbean nations. In particular, all the major Westminster system countries have shown strong trends towards multi-partism. For a time in 2010 indeed the UK, Australia, Canada, India and New Zealand (which moved to PR) all had coalition or minority governments – subsequently Canada moved back to a majority Conservative administration.

There are probably many reasons why political scientists have clung on to the bogus ‘Law’ for so long. American scholars are notoriously prone to ethno-centric thinking, and for them two party politics seems the ‘natural order’ of things, and coalition government dangerously fuzzy and anarchic. This slant is reinforced for rational choice theorists like Cox, who want neat mathematical models with clear equilibrium predictions. And the intuitive tug of Duverger’s two mechanisms (discouraging small parties from standing and voters from backing them) is still strong.

Here, though, new theory has hugely compromised the scope of the Law’s operations. For example, in a fine 2010 paper the US political scientists Eric Dickson and Ken Sheve use rational choice proximity models to predict that no contest should end up with more than two thirds of votes for one party. The logic here is that a local majority of 67 per cent or more can afford to split its vote across two parties, knowing that its biggest faction will still always win over any opposition party. By doing so, the majority of the large local majority can always advance their welfare. This logic works perfectly in the UK and India, as the charts above show (with no seats above the 67% majority level), but not at all in the USA.

There is a huge debate to be had about why Duverger’s law now is junk. Did the Duvergerian mechanisms once work, but have now ceased to apply? Have voters and parties ceased to worry about ‘wasting’ their efforts? Were Duverger’s ‘theory’ elements always wrong intellectually? And so on…

But for now, could political scientists just accept (at last!) that the ‘law’ is bust and cannot be revived or defended any further? Arguing this case with colleagues, I still feel like John Cleese in the famous Monty Python sketch, insisting on the completely, blindingly obvious. Duverger’s law is extinct. It has ceased to be. It is no more. This is a dead parrot.

This blog draws on recently published research by Patrick Dunleavy and Rekha Diwakar, ‘Analysing Multi-party Competition in Plurality Rule Elections’, in the journal Party Politics.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

It’s very odd seeing Canada mentioned here as an apparent example of a country that is not subject to 2-party domination, given that Canadians are very familiar with exactly that. Canada has essentially 2 political parties: the Conservatives, and everyone else on the more socially Liberal side.

At one point there were multiple Conservative parties and to consolidate their power they merged into one. Hence why they’re consistently dominant and in power, despite the electorate generally leaning towards social liberalism. They’re taking advantage of the inherent failure of plurality elections to lead to 2-party domination. The major party against them, the Liberal Party, and the secondary NDP Party both represent similar interests in opposition to the Conservative Party of Canada, but they want to remain separate in the interests of representation. This creates a nightmare choice: do you ask them to group together and form a single party in order to win elections on ballots, or do you keep them split, and be subject to vote spoilers thus allowing the conservatives to win elections?

The truth is they’d be better off joining in one political party, but that is EXACTLY what Duverger’s Law tells us. It is inaccurate to claim that Canada does not have 2-party domination when it is plagued by exactly that. Because we do not use an electoral system that allows us to express an opinion about all the candidates on the ballot (score voting), most of the seats won in our elections are won without any majority. It’s a disaster. For instance, this is the data from 2011:

Conservative 59 of 166 = 36%

NDP-New Democratic Party 67 of 103 = 65%

Liberal 32 of 34 = 94%

Bloc Quebecois 4 of 4 = 100%

Green Party 1 of 1 = 100%

Elections in Canada are fundamentally broken. The fact that the Liberal Party and NDP Party haven’t strategically consolidated to one party yet doesn’t mean that they’re not still subject to the failures of a 2-party domination oriented system. They literally cannot compete with a group that consolidates its party into a single dominant organism, because the election system is setup in such a way to favor 2 major parties above a wider selection of more subtly different parties. I suggest you read up on this and reeducate yourself on FPTP / plurality voting because you’ve come to totally the wrong conclusion: https://rangevoting.org/CanadaSeatsVotes.html

https://rangevoting.org/Plurality.html

It’s not just FPTP that does this either. Instant Runoff Voting / Ranked Choice Voting mathematically leads to the same issues of 2 party domination, as seen in Ireland and Australia: https://www.rangevoting.org/Ireland2002.html

https://www.rangevoting.org/AustralianPol.html

The error in this analysis is that Duverger’s Law has a second condition other than FPTP: winner take all.

All of the so-called exceptions to Duverger’s Law have proportional representation, making more than two parties viable. Even so, while Canada is technically a multiparty system, only two parties have ever held power. As I was reminded by an Indian immigrant at the polls earlier this week, India’s multiple parties are all socialist parties. So it is essentially a one-party system having a plethora of candidates with slight differences of policy. You can see it as a lack of lateral dispersion in your chart.

Duvergers Law also doesnt guarantee two parties all the time, but an equilibrium of two parties. We see this clearly in the 19th century when the once-dominant Whig Party in America fractured over the issue of slavery, the Republican Party rose to prominence, and all the Whig voters and politicians realigned with the two remaining major parties.

This post completely omits a key second part of Duverger’s law, which is that FPTP elections must take place in a system of *representative districts* (which is our constitutional structure here in the US) rather than a system of “proportional representation* (as in the British parliament). Apples, oranges, dishonesty.

Matt, Westminster’s House of Commons (which is where the data above is from) is FPTP with single-member districts, just like the US’s House of Representatives. You might be thinking of the devolved legislatures in Scotland and Wales, which are a mix of single-member and PR. There’s no dishonesty here.

Except that a parliamentary system allows for a third party to hold seats which then requires the major winners to reach a consensus to rule.

I think examining these data OVER TIME is critical. Looks like the study was done in 2011, so why was 2005 chosen for UK or 2004 for India? Why not many elections so that the pattern you suggest is seen as consistent over time? The Liberal Democrats got 57 seats in 2005….then they fell to something like 5-10 seats by 2010 and also 2015 (which you did not have data for in 2015, of course). So, what looked like a viable 3rd party petered out quickly thereafter. And in many years since late 1970s, a major 3rd party was there, but quite small. 2005 was a peak year for a 3rd party. Also, I think either Durverger or others afterwards also added that “regionalized” politics (like Quebec, Wales, Scotland) can create viable third parties with national prominence given the geographic concentration of voters with ‘non-national’ outlooks. I completely agree that Durverger is not “law-like” but I don’t think it is a dead parrot or completely defunct either. Its effects are seem to be still present, just other factors tweak and distort it, making a less-than-perfect fit. But nothing in social sciences is even close to perfect, like the regularity of the pull of gravity. (This is not my area of expertise, so I’m a relative novice).

Exactly! There are no physics-like laws in social sciences. It is really ignorant to “cancel” Duverger’s law just because it does not work in different contexts (almost none of which were taken into account in this research).

The systems examined all differ from the American system in one hugely-important respect: The party that leads their government is not directly elected, but instead selected by parliament, based on the allocation of seats in parliament. This makes the notion of coalition governments possible. In the US, the government is headed by the president, and it’s in that election that Duverger’s law shows itself most strongly. The battle for the presidency in turn biases the battles for house and senate seats, because it orients the focus on the two parties.

But these other countries are parliamentarist. Could it be that presidentialist countries with FPTP tend to become 2-party systems?

bingo.

Thanks a lot to Radical Centrist.

Your comment is completely correct on Canada, and I had meant to say “all had coalition or minority governments”, as the original blog does. We’ve now made that correction above, and I’m very grateful for the rapid feedback.

It is worth saying that Canada had three general elections in a row spread over six years that produced only minority governments, so this was a pretty chronic experience of Canadian voters refusing to give any party a parliamentary majority, despite repeated pushes by elites to force them to do so.

On whether Australia is a coalition government or a minority government – of course, this is a blurred boundary when you have “legislative agreements” with small parties or individuals to support a nominally single-party government. Gillard would not still be there today without signing up to something that looks a lot like a coalition agreement with people outside Labour’s ranks.

Thanks also, C. Terry for your insightful comment. I agree, and there is facinating paper by the Spanish political scientist Josep Colomer that makes the point that “It’s Parties That Choose Electoral Systems (or, Duverger’s Laws Upside Down)”.

Colomer shows that across history when countries transition from first-past-the-post or majority voting to PR voting systems then the numbers of parties rarely increases. Multi-party systems come into being before almost all such transitions, and that change only then forces the introduction of PR voting – rather than PR systems increasing the numbers of parties. The final (paid for) journal version of this paper is at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00514.x/abstract

For a free, open-web and slightly earlier version of the same piece, go to:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=849486

My view is that Duverger’s Law has it the wrong way around. It is not that FPTP creates two party politics, but that electoral systems are designed by politicians. A two party system reinforces majoritarian systems, whereas a multi-party one reinforces proportional ones.

I think there’s an error in the first paragraph after the “Facing facts, revising theories” header. You wrote that in 2010, the UK, Canada, Australia and India all had coalition governments (which is hyperlinked to another article. I think you meant all had hung parliaments. Canada certainly didn’t have a coalition government – we had a minority Conservative gov’t. Australia also did not (and does not) have a coalition government.