Anna Sanders and Rosalind Shorrocks examine the impact of austerity on vote choice in the last two general elections. They find that younger women were particularly anti-austerity and thus less supportive of the Conservative Party. However, the same was not true for older women, who were protected by the Coalition’s policies on pensions and were more similar to men in their assessment of their economic situation.

Anna Sanders and Rosalind Shorrocks examine the impact of austerity on vote choice in the last two general elections. They find that younger women were particularly anti-austerity and thus less supportive of the Conservative Party. However, the same was not true for older women, who were protected by the Coalition’s policies on pensions and were more similar to men in their assessment of their economic situation.

The gendered impact of austerity has been widely documented. The Women’s Budget Group estimates that, between 2010 and 2020, 86% of austerity cuts will have come from women’s pockets. This is largely because women are more reliant on state services, welfare payments, and they are more likely to work in the public sector. Yet we know relatively little about whether and how these policies have affected women’s vote choice in recent elections.

In our latest article in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations, we explore whether austerity policies led to gender differences in voting behaviour in Britain. In doing so, we use the British Election Study’s face-to-face post-election surveys to examine vote choice at the 2015 and 2017 British general elections.

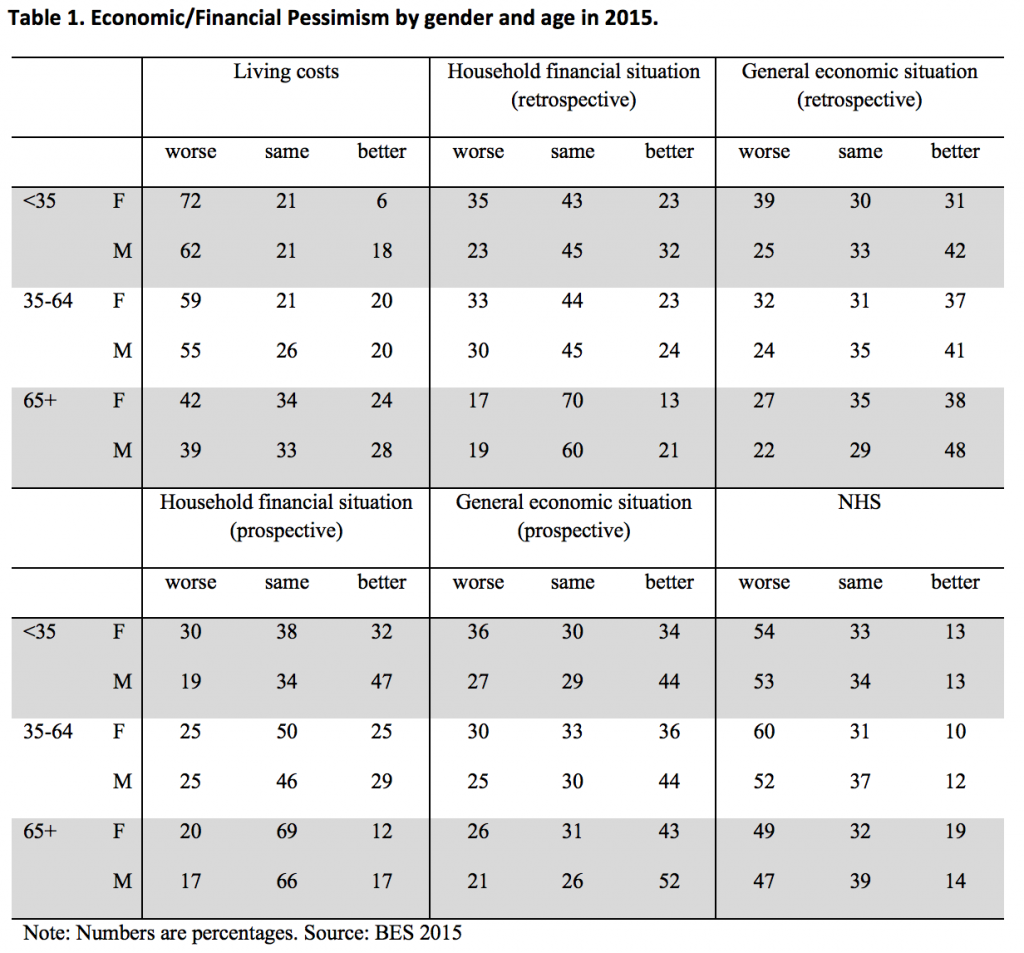

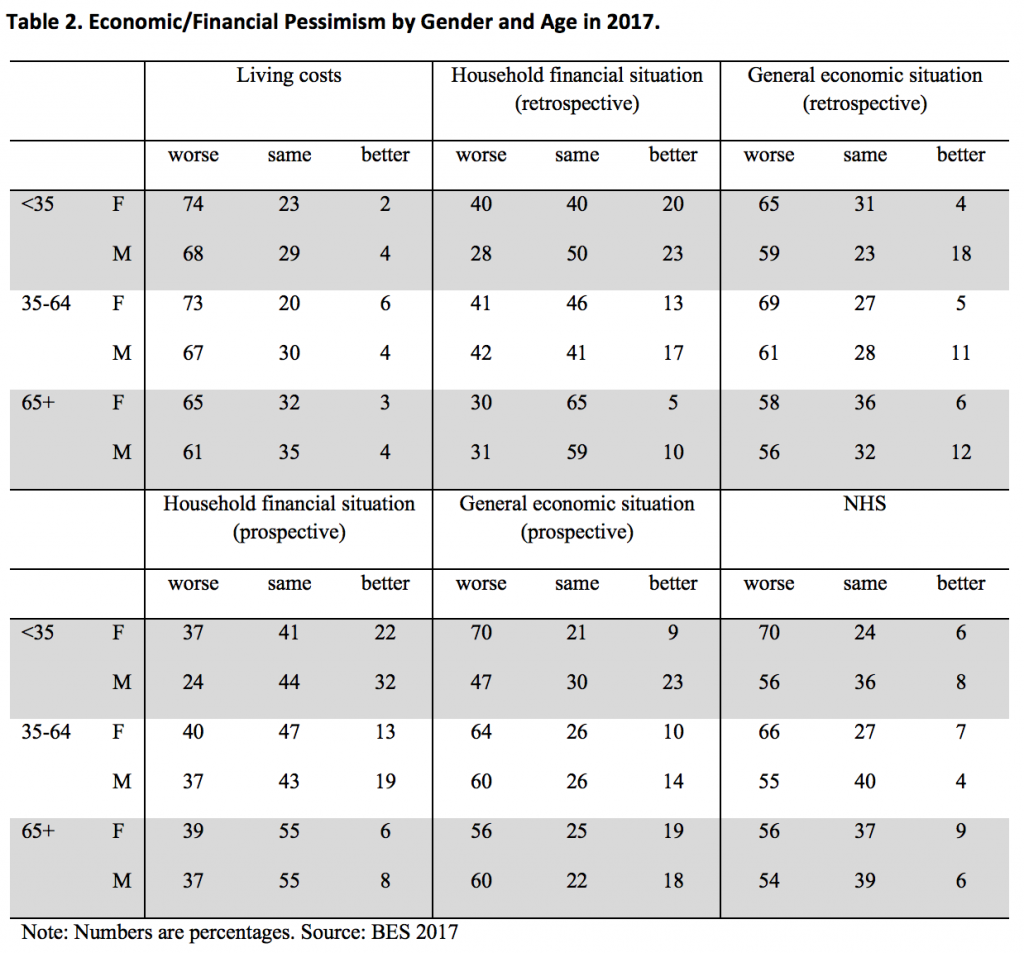

We find that in both 2015 and 2017, women were more likely than men to say that their living costs, household financial situation, the general economic situation, and the NHS had got or would get worse. Given the disproportionate impact of austerity on women, women’s economic/financial pessimism is perhaps not too surprising.

Yet the context of austerity suggests that economic/financial attitudes will differ not only by gender, but by life-stage. Women’s greater reliance on benefits and tax credits has meant that austerity measures from 2010 disproportionately affected women of a working and childbearing age – particularly BME women. Such measures included the abolition of child trust funds, the tapering of child benefit, and cuts to the ‘baby’ element of child tax credits. Meanwhile, thanks to policies implemented by successive Coalition and Conservative governments, older women have been somewhat protected from the harshest impacts of austerity. This was seen especially with the Coalition’s ‘triple lock’ on pensions, which was linked with a significant rise in the basic state pension relative to earnings. Between 2010 and 2016, the basic state pension – upon which women are more reliant as a source of income – increased by 22.2%, compared to a growth in earnings of 7.6% and a growth in prices of 12.3%.

These gender-age differences are reflected in economic and financial attitudes. Table 1 shows that women under 35 were consistently more likely than men their age or older women to think that their financial situation and the general economic situation had or would get worse. There is little gender difference at the older ages, with older women (65+) being no more pessimistic than older men.

Table 2 shows that by 2017, economic/financial pessimism had increased amongst all groups. Despite this growing pessimism, younger women under the age of 35 are still the most pessimistic, being much more pessimistic than men of the same age. Strikingly, in 2017 younger women were 23 percentage points more likely than younger men to say that the economic situation would get worse over the next 12 months.

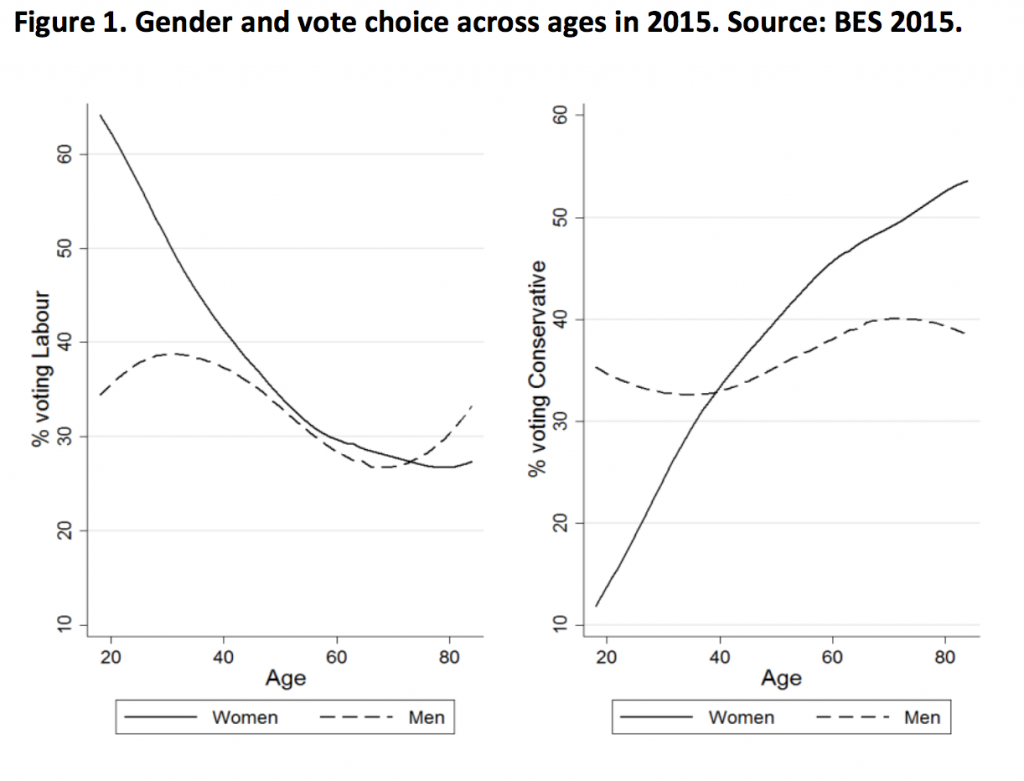

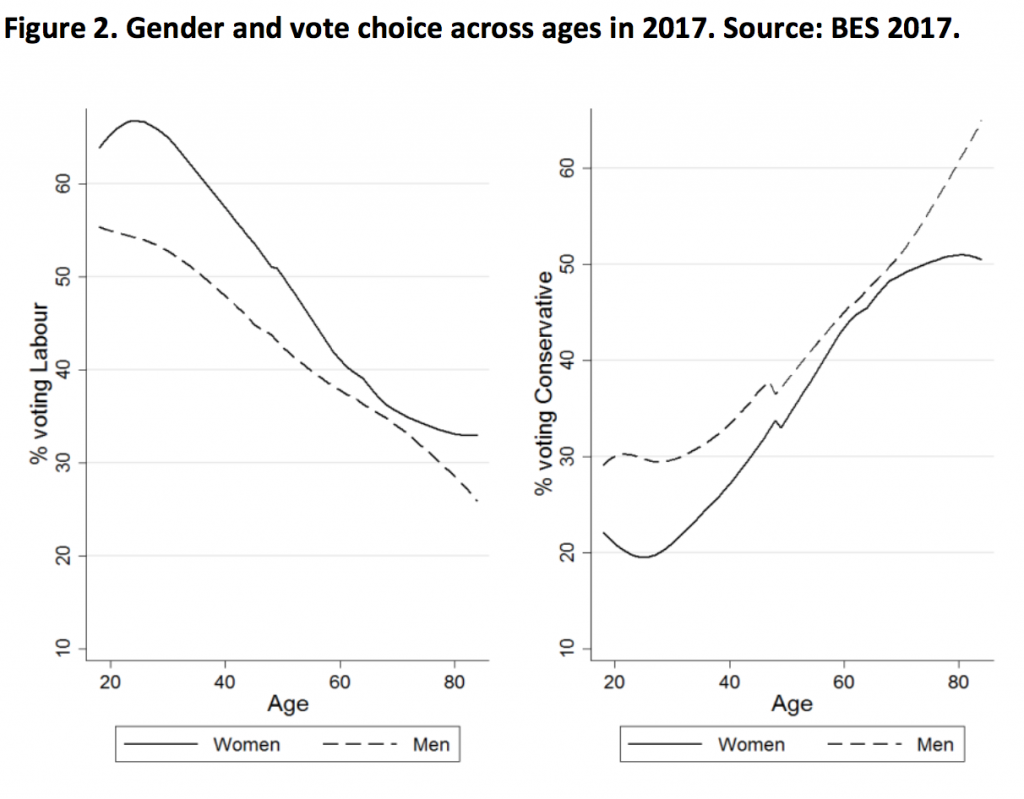

But do these economic and financial attitudes translate into gender-age differences in vote choice? We start by looking at how men and women voted in 2015 and 2017. Looking at Figures 1 and 2, we can see that younger women were more likely to vote Labour and less likely to vote Conservative than younger men at both elections. Younger women were also more supportive of Labour and less supportive of the Conservatives than older women. In 2017, gender differences amongst older age groups are smaller than in 2015, likely as a result of the collapse of UKIP, who older men were more likely to support.

Once we take younger women’s economic/financial pessimism into account, we show that they are no different to men in their vote choice. This is the case in both 2015 and 2017. This suggests that at both elections, younger women’s financial and economic pessimism was associated with their greater likelihood of voting Labour and reduced likelihood of voting Conservative. Notably, gender differences still remain at the older ages – even after taking economic/financial pessimism into account. Women over 65 are still more supportive than their male counterparts of the Conservatives, and accounting for economic/financial attitudes makes very little difference to their Conservative support.

Additionally, we find that younger women’s economic/financial pessimism contributed to age differences in vote choice between women. After we take younger women’s economic/financial pessimism into account, younger women are much more similar to older women in their vote choice in 2015.

In the context of austerity, Labour’s policies in both 2015 and 2017 would have been particularly attractive to women of a childbearing and working age. Many of these policies pledged to dismantle austerity measures that had been implemented by the previous Coalition and Conservative governments. These included pledges to abolish the under-occupancy penalty (otherwise known as the ‘bedroom tax’), reform Universal Credit, end the two-child policy on child tax credits and the ‘rape clause’, and reverse closures in Sure Start centres. These pledges likely appealed to younger women in particular, given their greater reliance on these payments and services. Meanwhile, Conservative pledges – especially in 2015 – likely appealed to older women voters in particular. These pledges included promises to retain the ‘triple lock’ on pensions, maintain universal pensioner benefits and pension flexibilities, which likely exacerbated the age differences among women that we find in 2015.

With the prospect of an early general election looming, it is clear that challenges lie ahead for both Labour and the Conservatives. For Labour, the party will need to consider how to reach out to older voters – particularly older women – with whom they have fared badly in past elections. While Labour did pledge to protect a range of pension-age benefits in 2017, some have raised concerns that such policies were not properly costed. Ensuring properly costed policies will provide a good starting point to ensure the party can reach out to older voters, who are already less likely to trust Labour with the economy.

For the Conservatives, the party will need to consider how to win back the votes of women, with whom they once had a lead. Continued austerity measures could have an impact on Conservative support not only among younger women, but among the party’s core base of older women as well. Despite the Chancellor’s promise of an ‘end to austerity’, there has been no mention of reversing the impact of austerity cuts already made. If the Conservatives are to restore their traditional lead with women voters, they must start by addressing their economic and financial concerns.

______________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work

Anna Sanders is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Manchester.

Anna Sanders is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Manchester.

Rosalind Shorrocks is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Rosalind Shorrocks is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

1 Comments