With the leadership of the European Central Bank set to change hands in November, Stefan Collignon assesses the bank’s performance under the outgoing president Jean-Claude Trichet, and finds that ECB under his leadership prevented meltdown of the European banking system and averted a global depression.

With the leadership of the European Central Bank set to change hands in November, Stefan Collignon assesses the bank’s performance under the outgoing president Jean-Claude Trichet, and finds that ECB under his leadership prevented meltdown of the European banking system and averted a global depression.

The appointment of Mario Draghi as president of the European Central Bank (ECB) after Jean-Claude Trichet is a moment to take stock. Since January 1999, the ECB has gone through three major phases: foundation, consolidation and financial crisis. Throughout this period it has achieved its primary and secondary objectives with remarkable precision, and it has also reacted appropriately to output and financial crises.

By estimating a reaction function between inflation rates and unemployment rates, we found that under Trichet, the reputation gained by the ECB in the early years and a more stable macroeconomic environment in the first half of his presidency allowed monetary policy to shift focus in favour of employment and financial stability. Handling the financial crisis was Trichet’s master piece. The ECB has slashed interest rates and provided liquidity through unorthodox methods, although member states have not made it easy for the bank to sustain financial stability.

ECB built a strong reputation, early

When the ECB started its operations in 1999, it was handicapped by large uncertainties. The new bank had no track record. Because monetary policy operates largely though communicating and sending signals to financial markets, the ECB needed to build up a “conservative” reputation and earn credibility as a tough inflation fighter, who is independent from European governments. The initial years were therefore characterized by a tight monetary policy stance.

However, contrary to a wide spread perception, the Maastricht Treaty does not ask the ECB to focus on price stability exclusively, although this is, of course, the ECB’s primary objective. The treaty also stipulates supporting economic growth and preserving financial stability, provided price stability is achieved. These ordered policy objectives allow us to assess the behavior of the ECB by estimating a Taylor-rule like reaction function, where the ECB responds to deviations from the inflation objective as well as economic activity.

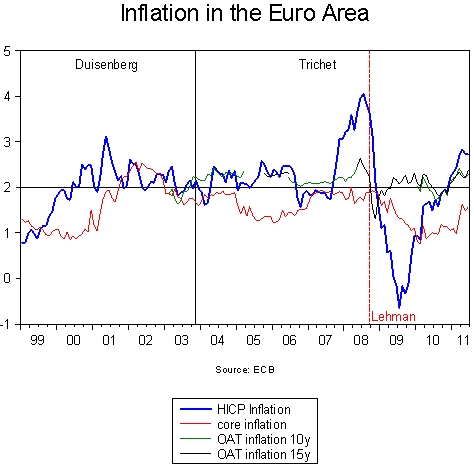

The ECB was remarkably successful in achieving price stability. Except for the peak in energy and food prices in 2006/7, actual and core inflation as well as inflation expectations measured by inflation-indexed OATi bonds were stable and close to the ECB target below 2 per cent, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1

Shift in focus to growth and employment

Once the ECB’s reputation was established and price stability ensured, Trichet could focus on the secondary objectives of growth and employment. We set out to asses the bank’s performance and analyse whether there was a regime shift from the first ECB president Wim Duisenberg, to Trichet

The econometric evidence can be summarized as follows:

- If we neglect interest rate smoothing, monetary policy from 1998 to 2008 was accommodating;

- If we introduce a smoothing parameter, monetary policy was stabilising during Duisenberg’s presidency but became accommodating with Trichet.

- A level shift suggests a break in the equilibrium values for inflation and interest rates, implying a more favourable macroeconomic environment for Trichet.

- The results from the forward looking specification are similar to those of backward looking results, indicating that the ECB has achieved a high degree of credibility as an inflation fighter, even if it has become slightly more accommodating under Trichet.

Crisis management

In the second half of Trichet’s tenure, the economic environment deteriorated dramatically. Inflation started to accelerate after 2005, and the ECB tightened its policy. In 2007, dangers in the US-credit markets became apparent and the crisis exploded with the Lehman collapse in September 2008. Euro Area GDP fell by 5.25 per cent, unemployment shot up and public debt to GDP ratios increased everywhere. Since 2009, the Greek debt crisis has continued to destabilize financial markets massively.

The handling of the crisis was Trichet’s finest achievement. In line with all major central banks, the ECB slashed interest rates to levels close to zero and it provided unlimited liquidity to stabilize financial markets. The ECB was able to prevent a meltdown of the European Banking system and cooperated with other major central banks in order to avoid a global depression. These policies did not ignite inflation and did not reflect a departure from our estimated Trichet reaction function.

In May 2010, after the European Council had agreed to set up the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), the ECB responded by buying sovereign debt in the secondary market. While this is a banal open market operation for most central banks in the world, it was innovative in Europe because the ECB used to provide liquidity to banks through repo operations rather than outright purchases. This policy shift gave the ECB an additional tool for preventing disruptions in financial markets and stabilizing the European banking system. Since 2010 it has made use of this procedure repeatedly, most recently to stabilize the bond markets for Spanish and Italian government debt. However, the operations have also made the ECB more vulnerable.

Sovereign defaults could have serious consequences for the ECB’s asset structure and own funds. Most importantly, however, the ECB has become involved in a power struggle with national governments, while some governments, especially in Germany, Slovakia and Finland, have resisted providing funds to overcome the liquidity crisis. Thus, the ECB under Trichet’s leadership was able to ensure a minimum of European coherence, which national governments failed to do.

We conclude by saying Bravo et merci, Monsieur Trichet! And Buona fortuna, Presidente Draghi!

This article is a shorter version of the draft paper European Monetary Policy under Jean-Claude Trichet, available online here.

Please read our comments policy before posting.