Jack Bailey estimates voters’ economic time frames using a new model that measures both how the economy affects voting behaviour and how voters remember economic change. He shows that after around a year and a half, economic voting effects halve in size. After five years, they approach zero. Yet he argues that economic growth over the past five years affects how people vote nonetheless. This is because as economic time frames grow, so too do rates of economic growth.

Jack Bailey estimates voters’ economic time frames using a new model that measures both how the economy affects voting behaviour and how voters remember economic change. He shows that after around a year and a half, economic voting effects halve in size. After five years, they approach zero. Yet he argues that economic growth over the past five years affects how people vote nonetheless. This is because as economic time frames grow, so too do rates of economic growth.

In 1992, three prominent political scientists argued that researchers had moved ‘little beyond introspection in understanding the processes by which citizens come to perceive economic movement’. Three decades later and we remain none the wiser. Like the early-1990s, research on the economy and voting now holds that voters look backwards but are short-sighted. They consider economic change when they vote, but only over the past year or so. Yet despite all the time that has passed, we still do not know just how short-sighted voters really are.

This matters: short-sighted voters allow governments to abuse their power. For example, short-sightedness allows them to have free rein early in their term, safe in the knowledge that the electorate will have forgotten their behaviour when the next election rolls around. Likewise, we might expect short-sighted voters to fall for the same old cheap tricks and pick not the best economic managers but, instead, the best economic manipulators.

I try to solve this problem in a new paper. While most similar research tests either how the economy affects voting behaviour or how voters remember economic change, I instead test both at the same time. To show how short-sighted voters are, I fit a special type of model to individual-level data from 34 different countries. My model estimates how long economic changes affect voters’ probability of supporting the incumbent party. The feature that sets my model apart from others is that it produces an estimate of the ‘half-life’ of any economic effects. Like an hour, a minute, or a second, a half-life is a unit of time. But, unlike these familiar measures, it does not reflect a fixed interval. Rather, it measures the average amount of time that it takes for the economy’s influence on voting to decay by half.

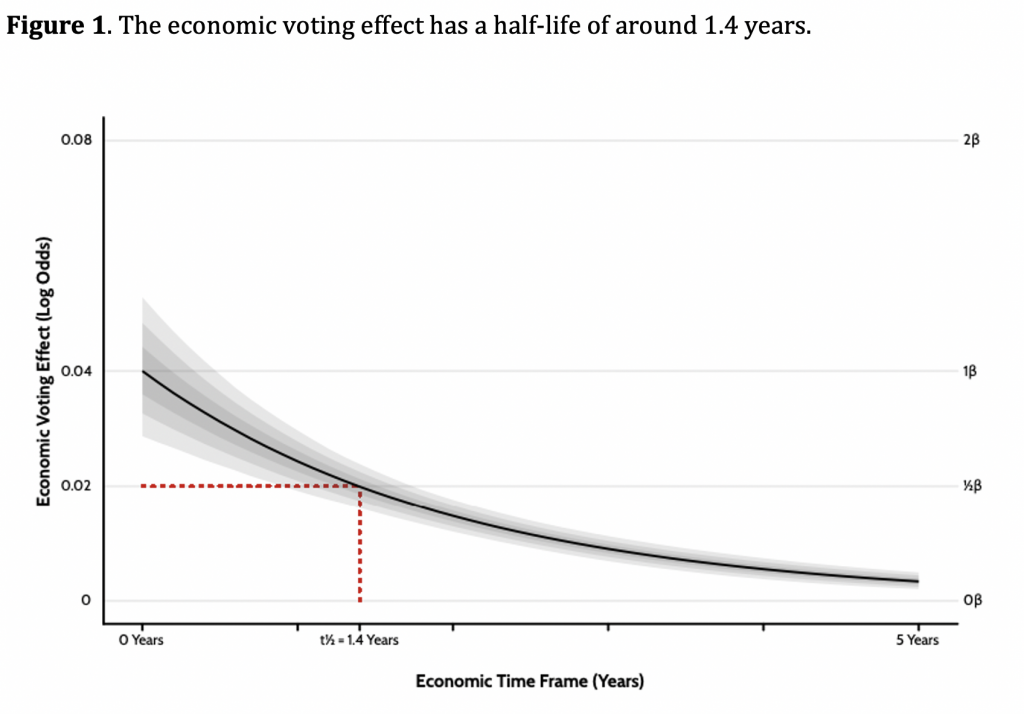

Figure 1 plots how the economic effect decays as potential economic time frames increase. As we can see, the economy’s effect on support for the incumbent government – otherwise known as the economic vote – decays for longer economic time frames. And the rate of decay suggests that the effect has a half life of about 1.4 years. This means that we should expect economic change that has taken place over the past 1.4 years to affect voters’ support for the incumbent party about half as much as any instantaneous economic change happening right now.

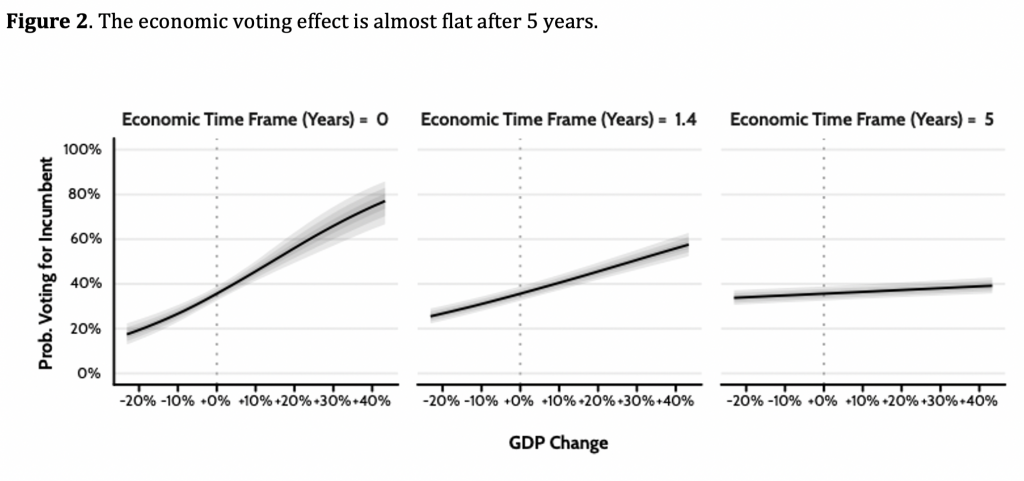

Figure 2 shows how the decay in the economic voting effect itself affects the probability that an average voter would vote for the incumbent party. The strength of the relationship between economic growth and incumbent support is very strong when economic time frames are at their shortest (left-most panel). Unsurprising, economic change over the past 1.4 years where the effect has decayed by half shows a weaker relationship (centre-most panel). And comparing the economy now to the economy five years ago is weaker further still (right-most panel).

Thus, a clear picture has emerged: as time passes, the effect that a given amount of economic change has on the choices voters make at the ballot box diminishes. This makes sense. After all, voters are only human and humans forget all sorts of things that we might otherwise consider important. But it is worth noting that economic time frames and economic change share a positive correlation of around 50%. This is because as time passes economies tend to grow. Thus, longer time frames also tend to coincide with more economic growth and the pattern of decay shown in figure 2 might not tell us the whole story.

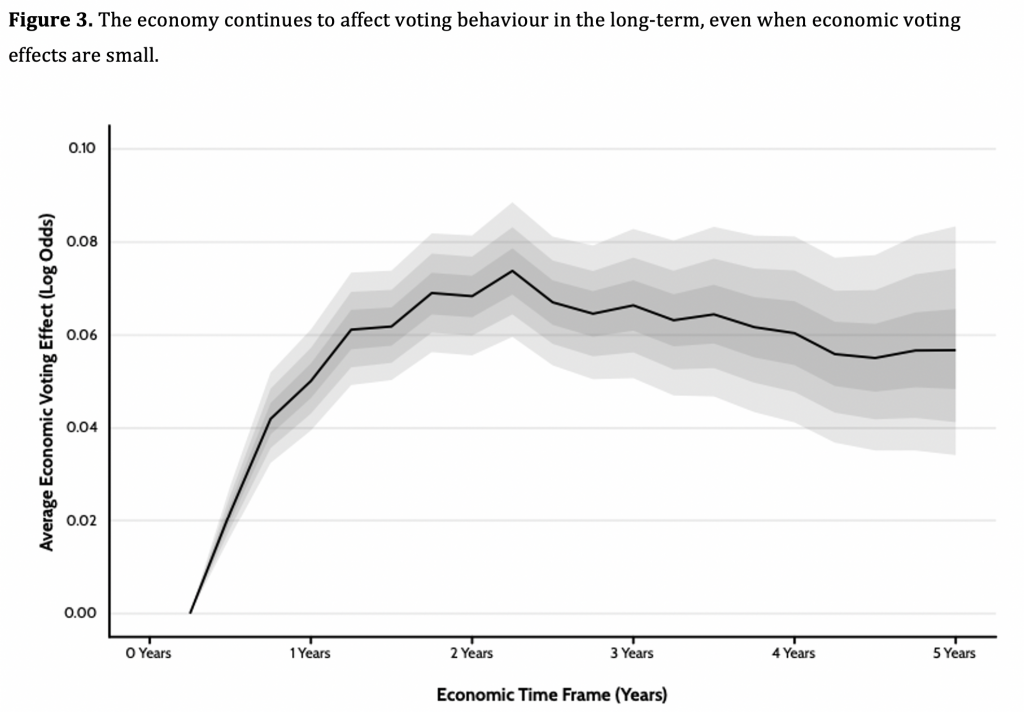

Figure 3 shows the average economic voting effect for different economic time frames based on the average amount of economic growth across the 34 countries in my data. Even if the economy’s effect is small, it can still have a reasonable and persistent impact on support for the incumbent party. Though the amount of uncertainty in this estimate balloons over time, it remains above zero even when comparing economic growth over the past five years.

My results show that voters are short-sighted. As economic time frames increase, so too does the effect of a given change in economic growth. Yet, this effect does not decay quite as fast as some past research would have us believe. It is not only economic change during the election year or even just the past few months that matters. Instead, the economy’s effect is strongest where economic time frames are shortest, falls to half its value after around a year and a half, then continues to reduce thereafter.

Even so, I also show that, while these effects might decay, the effective influence of the economy on how people vote does not (at least over the four- to five-year time span associated with most terms in office). This is because though longer economic time frames bring smaller economic voting effects, they also tend to bring greater amounts of economic growth on average. As such, voters’ short-sightedness and economic growth serve to counterbalance one another, thereby producing a sustained influence of the economy on support for the incumbent party.

In a way, this is a positive outcome. Voters are not perfect and they are certainly not all-knowing. But that they respond to economic change over a long period of time means that governments cannot treat them like fools. Rather, if they don’t deliver the economic goods, they’re likely to have to face the consequences of their actions.

____________________

Jack Bailey is Research Associate on the British Election Study and PhD candidate at the University of Manchester.

Jack Bailey is Research Associate on the British Election Study and PhD candidate at the University of Manchester.

Photo by Glen Carrie on Unsplash.