Ministerial proposals to establish elected city mayors in England date back to the early 1990s, but have struggled to gain traction, despite Tony Blair’s support for the idea. Stuart Wilks-Heeg argues that Thursday’s referendums underline that supporters of elected mayors, including the government, have failed to make a persuasive case. A likely lack of public enthusiasm for Police and Crime Commissioner elections later this year will make elected mayors an even harder sell.

Ministerial proposals to establish elected city mayors in England date back to the early 1990s, but have struggled to gain traction, despite Tony Blair’s support for the idea. Stuart Wilks-Heeg argues that Thursday’s referendums underline that supporters of elected mayors, including the government, have failed to make a persuasive case. A likely lack of public enthusiasm for Police and Crime Commissioner elections later this year will make elected mayors an even harder sell.

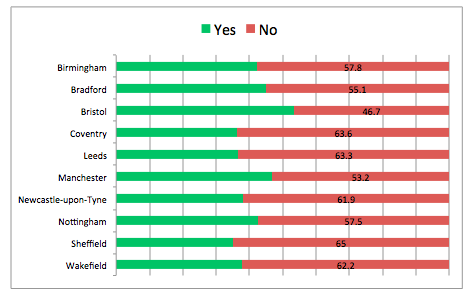

Voters in nine of the ten English cities which held referendums on Thursday have rejected the idea of adopting directly-elected mayors. As the chart below shows, only Bristol voted ‘yes’ to a mayor, with a clear majority of voters in the other nine cities opting to retain the existing system of a council leader and cabinet. The proposed change was most clearly rejected in Sheffield, Coventry, Leeds and Wakefield, but none of the ‘no’ votes, with the possible exceptions of Manchester and Bradford, could be described as particularly close.

Chart 1: The outcome of the mayoral referendums held in 10 English cities on 3 May 2012

The results will clearly disappoint advocates of directly elected mayors, who argued that they can boost local election turnouts, ensure local councils are more directly accountable to local electorates, and foster stronger city leadership, particularly around economic development objectives. There is some implicit logic to these arguments, even if the evidence available to support them is limited (before Thursday, there were only 13 elected mayors in addition to the mayor of London, and the experience had clearly been mixed). Nonetheless, given the claimed advantages, why were voters so reluctant to embrace the mayoral system?

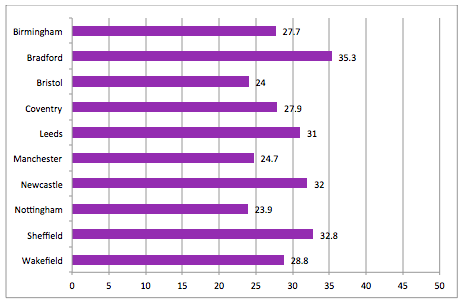

One reason was that no serious attempt was made to promote the case for elected mayors and to ensure that electors in the ten cities had the opportunity to debate the issues. The government itself did very little to explain the proposals to electors. Meanwhile, the ‘yes’ campaigns were lacklustre and will have made little or no impression on electors in most of the ten cities. The low salience of the issue is reflected in the turnout figures which, as the chart below shows, varied between 24 per cent in Bristol and 35 per cent in Bradford.

Chart 2: Turnout in the mayoral referendums held in 10 English cities on 3 May 2012

Making the case for elected mayors was not made any easier by the fact that it remained unclear what additional powers, if any, city mayors would acquire in each of the cities. Rather than define a new set of general powers for elected mayors, the government ran a consultation exercise, promising to establish bespoke sets of powers for each individual city. The consultation infamously yielded only 19 responses from members of the public, and by the time the referendums took place, no real progress had been made in clarifying how mayoral powers for each city were to be determined. Within each city, policy-makers want more powers and resources for transport and economic development, but on a city-regional scale rather than for the core cities alone. This is a view which many residents share, particularly in those areas which were part of the Metropolitan District Councils, abolished in 1986. A case for city-regional mayors, similar to the London model, may have had more appeal.

A final reason why voters were reluctant to embrace elected mayors may have been the way in which the question was phrased. Referendums tend to reinforce the status quo, particularly where most voters have little idea of what a proposed change to existing arrangements would mean in practice. By specifically asking voters if they would prefer to stick with ‘how the council is run now’ or otherwise adopt a system which ‘would be change from how the council is run now’, it is possible that the question prompted many voters who knew little about either system to stick with what seemed most familiar. It was not difficult for local councillors and parties opposed to the change to raise serious doubts about the virtues of moving to a mayoral system. Given a particularly negative London mayoral campaign, those details of London’s Boris and Ken show reached voters in other English cities are only likely to have played into the hands of those resisting the change.

Proposals for elected city mayors have long struggled to gain any real purchase in British politics since the idea was first mooted by Michael Heseltine, as Secretary of State for the Environment in John Mayor’s Conservative government, in the early 1990s. Under Tony Blair’s premiership, central government embraced the idea enthusiastically, yet all but a few local authorities opted to move to a leader and cabinet model ,rather than to an elected mayor.

None of this had dimmed Conservative enthusiasm for elected mayors, until yesterday. But nine cities rejecting the government’s proposals for elected mayors is a clearly major blow for the coalition’s localism agenda. It seems unlikely that any further attempt to introduce city mayors will be made in the current parliament, although it is not impossible that local campaigns to move to a mayoral system will emerge, particularly in light of the adoption of a elected mayors in Liverpool and Salford, and now Bristol, so far this year. If Liverpool, for instance, appears to be advantaged by having an elected mayor, whether in terms of having the ear of government, or in becoming better placed to attract inward investment, it is clearly conceivable that Manchester or Leeds will decide to follow suit.

In the medium-term, however, the prospects for more widespread adoption of elected mayors is likely to be strongly influenced by the experience of Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) elections, the first of which will be held in Autumn 2012. If, as many expect, the public show little appetite for PCC elections, the case for directly-elected mayors will become increasingly difficult to make. The prospect of the Conservatives being able to boast that they have established ‘a Boris in every city’ seems as distant as ever.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Dr Stuart Wilks-Heeg is Director of the research and campaign group Democratic Audit and a Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at the University of Liverpool.

All excellent points, Stuart….

I have been in favour of a proper debate on localism (perhaps best to be represented in future by elected mayors?) for years, and even I found it very difficult to promote any meaningful discourse. I have serious misgivings about central government’s current political motives for mayors, but these are important issues which deserve far more attention than thus far publicly accorded.

And there is one particular aspect, however, about which I am especially vexed almost the entire discussion seems to have been couched in terms of what ‘he’ will do if / when an elected mayor takes post.

OK, there were a couple of women candidates for mayor in London; but then none at all e.g. for Liverpool! So perhaps a lot of ‘ordinary people’ (half of them female) think this is not a conversation of much relevance to them?

Has ‘localism’ eclipsed the so-called softer issues which concern more women than men?… Watching over several years now, I suspect it has.

This is an issue which the political parties must consider from their centres out, rather than blaming individuals because these fallable folk don’t seem engaged: http://pinkpolitika.com/2012/05/03/age-related-sexism-women-candidates-for-mayor-and-commissioner-elections/ [article written by me].

It’s my call that localism in any sense won’t work properly until it’s more gender (and other ‘minority’ interest) responsive. The dialogue on the ground will need to accommodate difference a lot more than it does now before it becomes real to most people; and the political responses will have to do the same.