Support for Brexit was higher among those who identify as English rather than British, even after accounting for relevant economic factors. But what is it that connects English identity to a preference for Brexit? Anthony Heath and Lindsay Richards outline some key characteristics that go some way in explaining the association.

Support for Brexit was higher among those who identify as English rather than British, even after accounting for relevant economic factors. But what is it that connects English identity to a preference for Brexit? Anthony Heath and Lindsay Richards outline some key characteristics that go some way in explaining the association.

‘Identity politics’ is a phrase that can be heard a lot these days, although it has been around for a while. It’s a phrase that captures the idea that people are forming political preferences on the basis of who they are (or who they feel they are) and the groups they belong to. This is in contrast to the ‘classic’ treatments of British politics which tended to focus on divisions between social classes, their economic interests, and the left-right ideological dimension which pitted free market policies (of the sort particularly associated with Margaret Thatcher) against the kind of socialist policies followed by the Atlee government. In this classic divide, political choices follow one’s own economic position, with the well-off voting for lower taxes and lower redistribution (the Conservatives) and trade unionists and the worse-off voting for the opposite (Labour). But, while economics has been highly relevant to the debates over Brexit, issues over identity, particularly national and European identities, are also an important part of the mix.

“When you strip away the rhetoric”, wrote Fintan O’Toole in the Guardian in June 2016, “Brexit is an English Nationalist movement”. Englishness has also been called “the invisible driver” behind Brexit. These assertions have been borne out by a number of post-referendum studies that have demonstrated higher support for Brexit among those identifying as English rather than British (see here for example). Importantly, in light of the ‘classic’ political divides, these findings about Englishness hold true after accounting for relevant economic factors; that is, identity matters over and above any economic concerns the individual might hold.

And it is an English phenomenon: the distinction doesn’t hold in Scotland or Northern Ireland or Wales. But just what is it about Englishness that connects one’s feeling of belonging to the nation to preferences for Brexit? Do the English identifiers place greater emphasis on nationalism, on protecting national boundaries? And is Englishness an ‘ethnic’ identity where Britishness is more ‘civic’?

National identity represents a social identity. According to social identity theory a social identity represents a self-concept based on perceived membership of a social group and is associated with in-group favouritism and discrimination against members of outgroups. Conceptually similar is the idea that national identity/membership of a nation represents membership of an imagined community – imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign. A nation always implies a boundary between those who are conceived to belong to it and those who are excluded from membership. Key ideas in both set of theories are that boundaries between members and non-members exist, and that feelings differ towards those on different sides of the boundary.

We can think of these symbolic boundaries as being more, or less, “bright” or “blurred”. In effect the brightness of the boundary tells one how easy it is to cross the boundary and for newcomers to be accepted as a member of the specific national community. A further set of distinctions include the criteria for crossing the boundary and being accepted as a member of the national community in question.

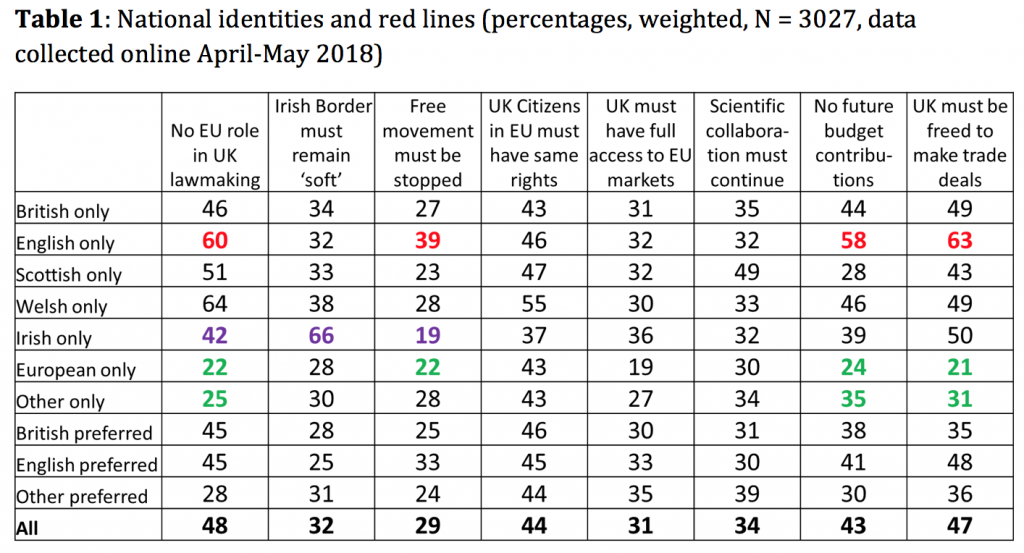

To explore these ideas – of nationalism, of symbolic boundaries, and of nativism – we investigated how Englishness and other identities are linked to Brexit preferences. In our on-going Brexit survey, we asked respondents about various aspects of the Brexit negotiations: what would be their ‘red lines’ and where would they be willing to negotiate? (Read more about these attitudes here.)

Our results (table 1) show that exclusive English identities are associated with a hard Brexit, with strong emphases on the red lines of regaining sovereignty, ending free movement, ending budget contributions, and restoring the freedom to make independent trade deals. European (and other) identities are associated with significantly weaker emphases on these red lines, with British identities falling somewhere in between. Irish identities are distinctive in their emphasis on maintaining a soft border in the island of Ireland.

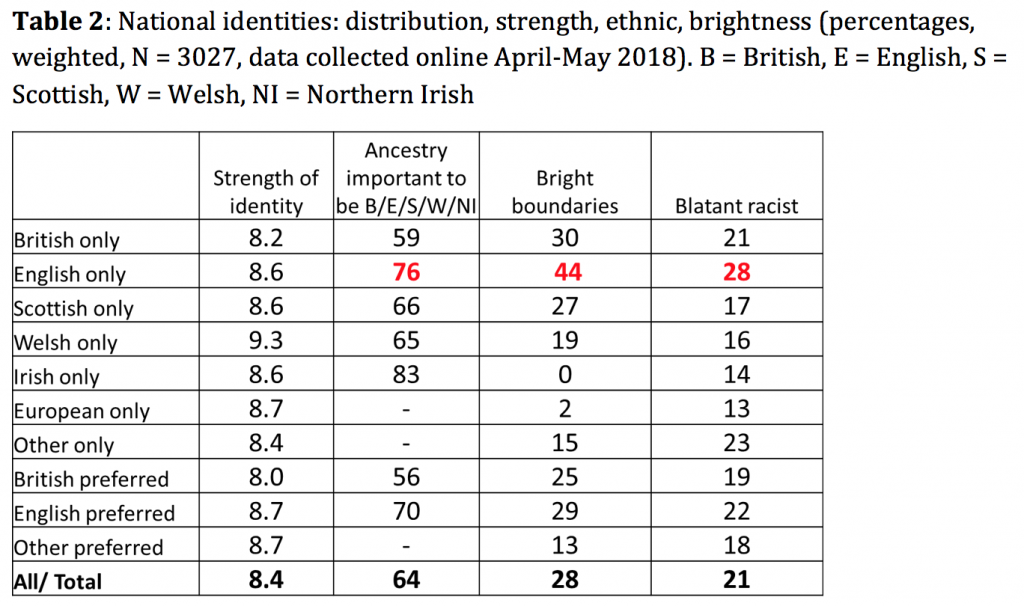

We also collected measures of people’s symbolic boundaries by asking how important various factors are for being English/ Scottish/ Welsh/ British etc. The questions included the importance of ancestry, speaking the language, respect for laws, and being born here. We also asked a set of questions intended to garner beliefs in biological racism. We asked, for example: “Do you agree that some races or ethnic groups are born less intelligent than others? Do you agree that some races or ethnic groups are born harder working than others?” From these we derived a measure of ‘blatant racism’ for those who agree with these questions (in contrast to those who disagree but may hold more ‘subtle’ forms of racist views).

In table 2 we can see that an exclusive English identity does seem to have a distinctive, rather ‘nativist’ or ‘ethnocentric’, character with bright boundaries against outsiders and an emphasis on ancestry as a criterion for national belonging. People who subscribe to an exclusive English identity are also more willing to express racist views, while those with European identities tend to be the opposite.

Our research shows that these characteristics go some way towards explaining the association between an English identity, a preference for a hard Brexit, and the red lines of restoring British sovereignty and the ability to make independent trade deals and ending free movement and budget contributions to the EU. This is not to deny that there may simultaneously be affinities between these Brexit red lines and Margaret Thatcher’s free market vision with its emphasis on deregulation, a small state, and consumer choice. Identity politics is not necessarily antithetical to economic ideology. Perhaps the power of the Leave movement was its ability to harness these two sorts of politics together.

____________

Anthony Heath, CBE, FBA is the Director of the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford. He is Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the University of Oxford and Professor of Sociology at Manchester University.

Anthony Heath, CBE, FBA is the Director of the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford. He is Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the University of Oxford and Professor of Sociology at Manchester University.

Lindsay Richards is Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford.

Lindsay Richards is Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

The fact that “English” is spoken all over the world means that we must not rub people’s noses in it by asserting our patriotism. One instantly starts to sound like Enoch Powell.

What this research fails to acknowledge is the fact that Englishness is still a “forbidden” identity, often conflated with “Britishness” as a consequence. If I may paraphrase Neil Ascherson, Englishness has slumbered under the cloak of Britishness for 300 years, and as that cloak is slipping off it has awoken in a sour temper. Many English people actively do not define themselves as English due to the negative connotations of racism and reactionary politics with which they don’t wish to be associated.

The constitutional infrastructure of the UK is under strain as never before. A rebirth of Englishness as a mainstream identity would threaten the British establishment hegemony so it’s both convenient and necessary to cast Englishness as too big and too ugly to predominate within the UK.

This surely skews your sample. The toxification of Englishness leads to a situation where English people who aren’t “blatant racists”, to coin your term, fear to define themselves as English thus leaving much of the territory of Englishness occupied by those who are “blatant racists” or who don’t care much if people think they are.

As well as skewing your sample I do think this research unwittingly contributes to the problem, not to the solution, which is the detoxification of how Englishness is perceived. I think the title of this article: “Nationalism, racism, and identity: what connects Englishness to a preference for hard Brexit?” is especially unfortunate in this regard.

Michael, don’t you think it a little odd that 84% of the UK population live in England yet somehow they have been forbidden to use English as a description of their identity. Forbidden by whom? This is quite like the thought I’ve heard expressed that England is unique in the UK by not having its own parliament, and therefore there is a democratic deficit. Obviously this is technically correct in one way, there being no devolved English administration. But since it is impossible for England (represented by 533 MPs of English constituencies out of a total of 650) to be out-voted at Westminster, there doesn’t really seem to be any need for one.

English people have chosen to conflate England and Britain for a long time, possibly for hundreds of years. It seems only now is a sense of Englishness re-establishing itself. It’s only a pity that it’s the quite dark nativist aspect of Englishness which seems to be shaping the future under Brexit.Those people are, in my estimation, by no means the majority. What worries me is that the majority seem to be reasonably prepared to go along with it.

There is a need for Brexitherapy at the moment. I am patriotic, not racist. The big businesses, too many M.P.s and the national press are all Remoaners. So you are not hearing how angry people like me are becoming. We have been betrayed. It will not just be the donning of yellow vests. We want the Burghers of Brussells to stop treating N.Ireland as their new ‘colony’ and leave us to self-govern. It’s not more simple than this.

Jim, I guess you’re filtering out the loud voices like Dr Kehinde Andrews – “The English flag isn’t just ‘a’ symbol of racism, it may be the primary symbol of racism in this country”. No, it’s not like he’s a writer for the Guardian or anything.

Whatever conclusions are drawn by the author, one thing is clear. Despite being told that there is no such thing as English, politicians saying ‘this country’ or Britain when they are talking about England, a lack of English political institutions, sneering at things like St George’s Day while celebrating St Patrick’s Day, saying the English flag is racist and so on and nauseum, we English are fighting back.. A lot of people now identify as English and that is a significant fact in UK politics. Ignore us at your peril!

There is a resentment or at least a bafflement and sense of unfairness in the minds of many English people against the fact that current and historic nationalism (and the corresponding embodiment of them in emerging national pollical structures culminating in nationhood) is seen as good and progressive for the Irish, the Scots, the Indians, the Palestinians and the Catalans, but that for England it is bad. It feels as if England is being unjustly held to a higher standard than other countries. Now, I understand why this is the case historically. It has to do with colonialism and subsequent decolonisation. It is simple historical fact that UK-Irish encounters in the past tended to have Ireland as the oppressed and the UK as the oppressor. Being on the side of the underdog or just simple justice in such circumstances would lead a progressive to be more inclined towards Irish nationalism than British nationalism. BUT that was then, this is now, the Empire has gone and those who remember it have mostly died. The average English person today doesn’t feel as if he is the oppressor and yet any stirrings of English nationalism are answered with cries of racism or accusations of little-Englanderism.

Brexit is connected to the UK’s post-imperial role. But not in the way most people think. It isn’t about trying to recreate Empire 2.0. For some Brexiters it is about looking at how well successful other countries have become since throwing off foreign-rule and deciding that we’d like a bit of that ourselves. The EU may or may not be an appropriate target for such feeling, but the feeling is real enough.

I have to agree with Tim, above.

The thing that connects Scots, Irish, Welsh and British identities is that they all have national democratic political institutions and representatives, for the most part promoting a civic nationalist (plural, inclusive, tolerant, multicultural) form of those identities.

English identity has no such luck. Not only is England denied institutional political expression but the very word ‘England’ is not mentioned by the UK political class. Witness Matt Hancock speaking at the Conservative Party Conference on Health and Social Care in England without mentioning England once (he mentioned ‘Britain’ twice & ‘our nation’, ‘this nation’, ‘our country’, etc. – anything but England).

Even worse was James Brokenshire who spoke for 19 minutes at the conference on English housing, communities and local government without once mentioning England. Brokenshire may not be able to say England but he did say ‘Britain’ (5 times) and ‘our country’ (7 times).

Labour and the Lib Dems do exactly the same.

If you want a more inclusive English identity then acknowledge England as a political community in which everyone is a stakeholder (irrespective of class, ethnicity, national identity or birth) by letting us elect an English parliament and government.

Interesting but inconclusive. You seem to be saying that people who identify as English /tend/ to be a bit more racist and a bit less EU-friendly than English people who identify as British and/or people who are Scottish, Irish, etc. I can’t argue with that, but is it not the case that the UK has over recent decades become less racist? English people today are less racist than English people in the 1970s just as Scottish people today are less racist than Scottish people in the 1970s. Progress may be uneven across the nations (and maybe complicated by sectarianism-as-a-different-kind-racism in Scotland and Ireland), but the arc of history tends towards diminishing racism so offering racism as an explanation for Brexit requires you to answer why the UK became more anti-EU simultaneously with it becoming less racist.

And might the reason that Englishness tends to be a more nativist identity rather than a political/civil one be because unlike Scotland (and to a lesser extent Wales and NI) the English have been denied any pollical/civil recognition as a unit? It is hard for Englishness to be a civil identity concept without structures of civic society (parliaments, language, national government etc) for it to hang off.

Yes. And your point is?

The number that really leaps from the page is the 83% of Irish who think ancestry is important in being Irish. I think if you’re going to use survey data to comment on nationalism and politics, that number deserves a comment particularly as you reference Fintan O’Toole earlier.

Could that be as simple as Irish nationality law? I am lead to believe that having a half Irish grandfather makes you eligible for an Irish passport even if neither you nor your parents have set foot on the Emerald Isle.. From a legal point of view having Irish ancestry *is* important.

Tim – Could that be as simple as Irish nationality law? – well I guess it could, but the existence of such a law is revealing. We don;t have any such equivalent law for being English, and any attempt to have such a law would undoubtedly be regarded as racist (which it clearly is).

I think an obvious reason for the rise in English nationalism and associated racism is the rise in non-English nationalism and identity politics across much of the UK. If we are to live in an identitarian world, where one’s lot in life is determined not by your individual qualities but by the labels society decides to put on you, it shouldn’t be a surprise when people begin to align their politics to those identities.