While the No Deal parties may have won the 2019 EP election in terms of seats, the clear winner were the explicitly pro-Remain parties, explains Thiemo Fetzer. He also illustrates how the electoral losses of Labour and the Conservatives appear not to be aligned across the Leave vs Remain dimension that the referendum revealed, highlighting further the need for the two parties to articulate a clear policy on Brexit.

While the No Deal parties may have won the 2019 EP election in terms of seats, the clear winner were the explicitly pro-Remain parties, explains Thiemo Fetzer. He also illustrates how the electoral losses of Labour and the Conservatives appear not to be aligned across the Leave vs Remain dimension that the referendum revealed, highlighting further the need for the two parties to articulate a clear policy on Brexit.

The underlying changes in support for Brexit and, in particular, no deal Brexit that are becoming increasingly clear in opinion polling have influenced the 2019 European Parliament election. The results suggest that the substantive gains of pro-Remain parties were distinctly larger compared to those of No Deal parties, even in the most pro-Leave districts. Meanwhile, neither the Conservative nor the Labour party’s losses appear associated with an area’s 2016 support for Leave.

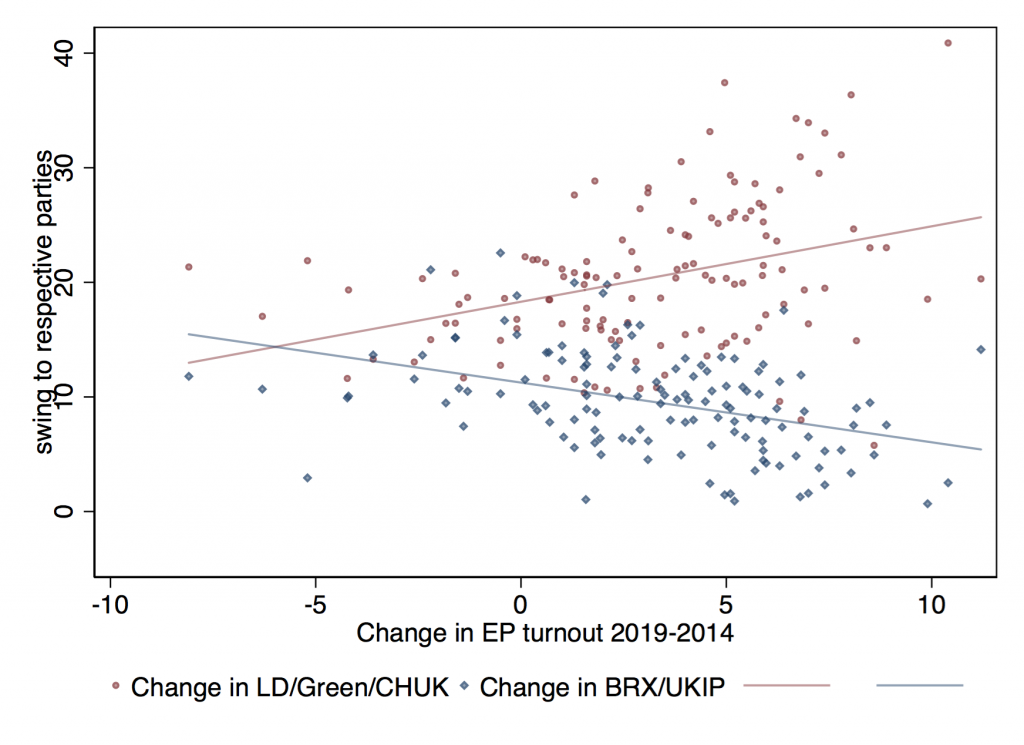

This may indicate substantial changes in the composition of the turnout. Incomplete turnout data does suggest that the gains for the pro-EU parties are particularly concentrated in areas that saw the most marked increase in turnout relative to the last EP election in 2014. This pattern holds in reverse for the No Deal advocates.

The 2016 referendum and the electoral swings in 2019

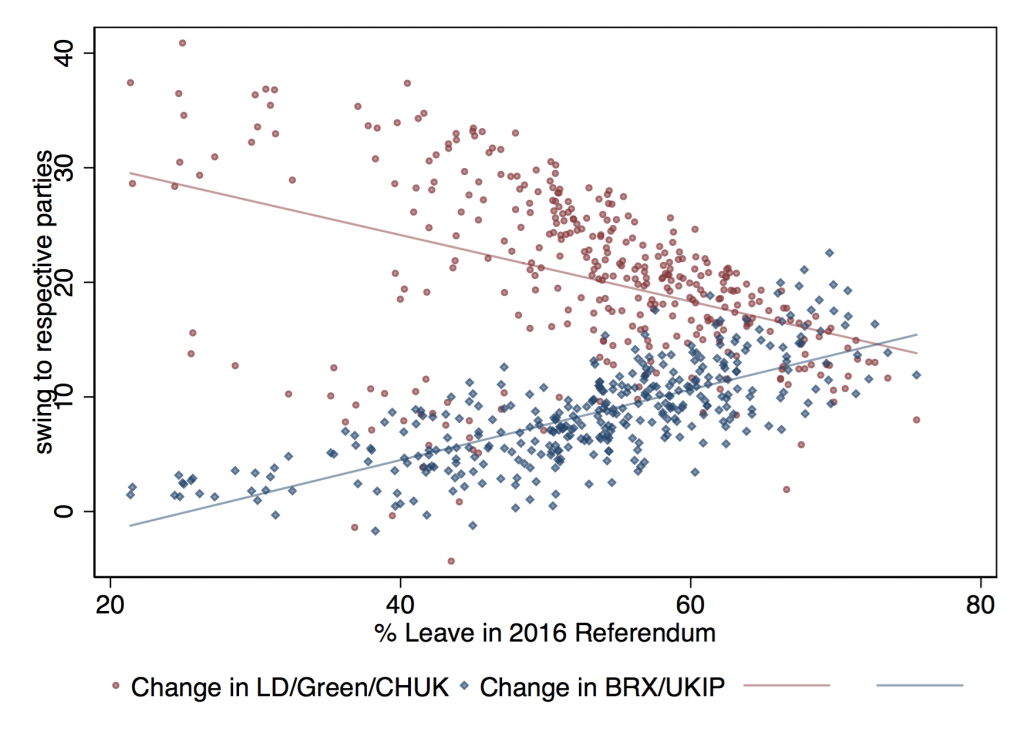

What happened in the 2019 EP elections is probably best presented in Figure 1, which summarizes the swings for the parties with an explicit policy on the EU issue relative to the 2014 EP election. Support for the Brexit Party and UKIP has increased most in those parts of the country that saw the strongest levels of support for Leave in 2016. On the other hand, support for the explicitly pro-Remain parties has increased most in the parts of the UK that voted in favour of Remain.

The net difference, however, is clearly in favour of the explicitly pro-Remain parties: almost across the board is a stronger increase in support for the unambiguous pro-Remain parties, compared to those advocating a hard Brexit. If those turning out in the EP elections were a representative sample of the population living in a district, then weighting by the size of the electorate, e.g. in 2016, would suggest that pro-Remain parties gained 20 percentage points in votes, while explicitly pro-Leave parties only gained 8 percentage points. In 71 out of 360 districts, the Liberal Democrats, Change UK, and Green Party vote share combined was above 50% of the vote. For the Brexit Party and UKIP this was only the case in 48 districts. In contrast, in 2016 the vast majority of districts saw a plurality for Leave.

Figure 1: Vote swings between the 2014 referendum and EP 2019

Are the Labour and Conservative losses aligned along the 2016 Brexit divide?

Are the Labour and Conservative losses aligned along the 2016 Brexit divide?

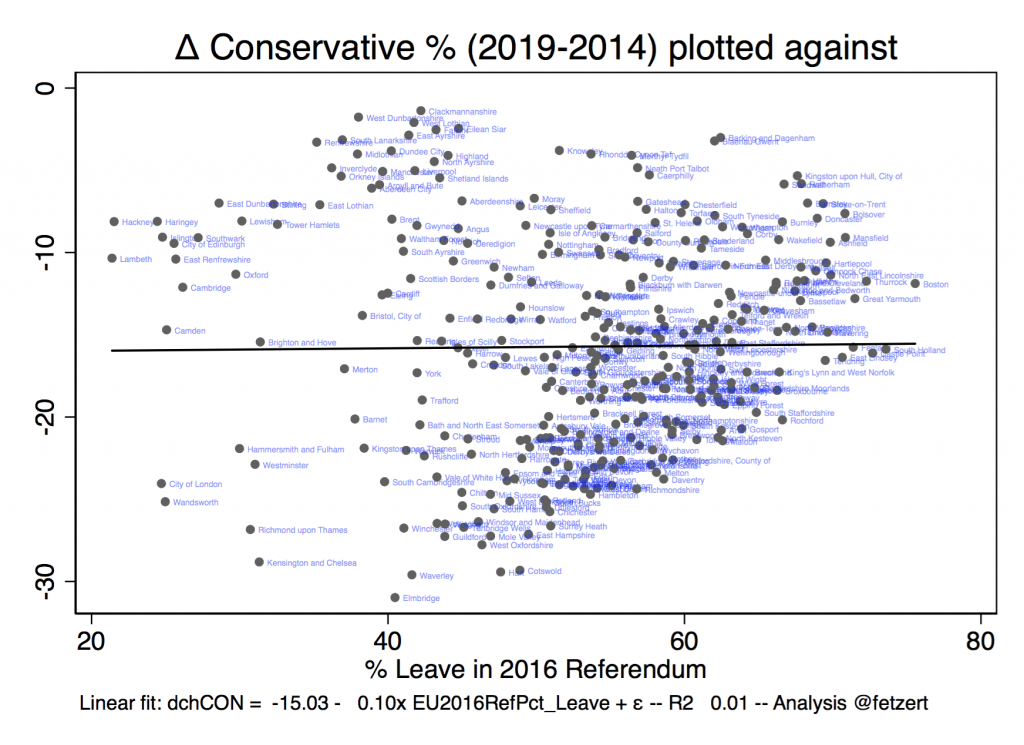

Given the shifts in electoral support, a central question for Labour or Conservative Party strategists is whether their losses may be due to their approach to Brexit. For the Conservative party, there appears to be a flat relationship between their electoral losses along the 2016 Brexit divide. In other words, while the Conservatives dramatically lost votes across the board, these were not concentrated in the most pro-Leave districts. This is important, as it suggests that the average Conservative voter, even in Leave supporting areas, may be much less inclined to support a No Deal Brexit, compared to the Conservative Party membership. The fact that the membership is out of sync with the general public, and even with Conservative voters, is not a surprise. Without the support of moderate Conservatives, this may be consequential and can produce an electoral wipe-out for the Conservative Party in future elections – with only the first-past-the-post system possibly preventing a thrashing.

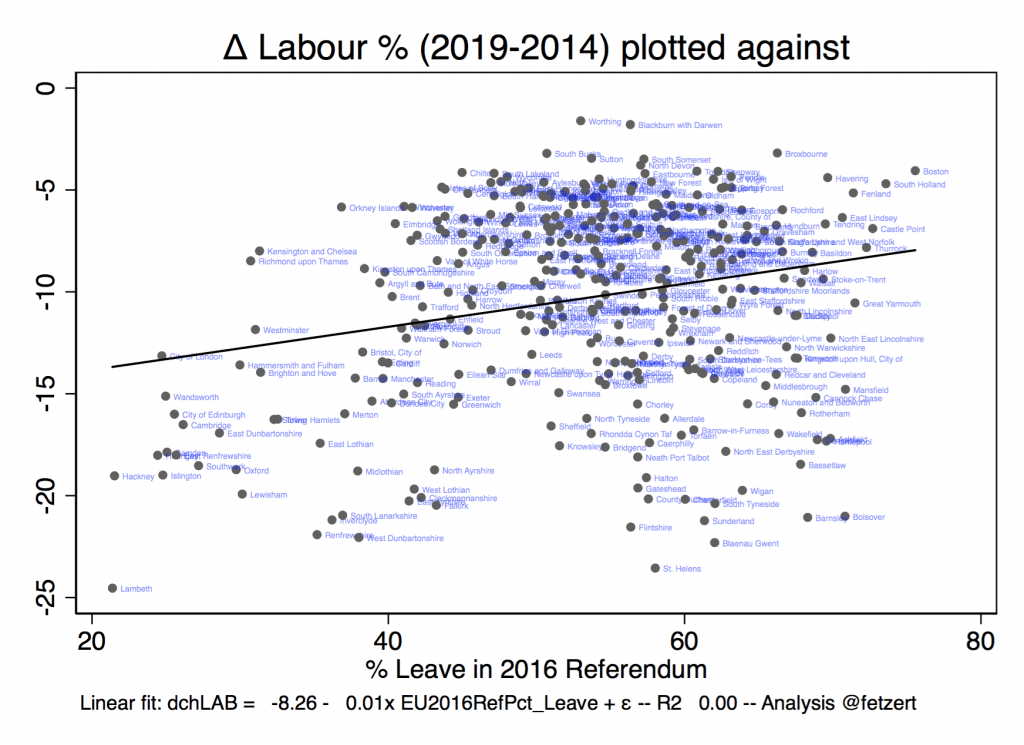

For Labour, there appears to be a very weak positive sloped relationship. Without a careful read, this would suggest that Labour did loose distinctly more support in the most pro-Remain areas. Yet looking at the R2 and indeed, even the coefficients, the 2016 vote seems hardly able to explain where Labour lost in vote share – which is similar as for the Conservative Party. This highlights that neither parties’ losses can really be explained by the Leave or Remain divide that was opened up in 2016. Rather, it may suggest that the referendum was decidedly swung by a change in the composition of those who turned out.

Figures 2 & 3: Conservative and Labour vote swings between the 2014 and 2019 EP

Turnout in 2016 may have been remarkable, yet micro level data suggest that especially those who did not vote in 2016 are more likely to be unhappy about the referendum outcome. A comparison of electoral gains in 2019 vis-à-vis 2014 and turnout in the 2016 referendum does suggest an important pattern: support for explicitly pro-Remain parties grew distinctly more vis-à-vis support for hard-Brexit parties, and this is happening across the board, no matter what the levels of turnout were back in 2016.

Figure 4: Electoral gains in the 2014 and 2019 EP, and turnout in the 2016 referendum

At the time of writing full turnout data is not available, though among the districts for which data was available, the 2011 census population weighted turnout suggests it increased by 3.5 percentage points relative to 2014. This increase is not that large, which is particularly interesting, given the salience of the European topic over the past three years and also, due to concerns that thousands of EU citizens in the UK and British citizens abroad may have been disenfranchised.

At the time of writing full turnout data is not available, though among the districts for which data was available, the 2011 census population weighted turnout suggests it increased by 3.5 percentage points relative to 2014. This increase is not that large, which is particularly interesting, given the salience of the European topic over the past three years and also, due to concerns that thousands of EU citizens in the UK and British citizens abroad may have been disenfranchised.

Yet, even if turnout did not increase by much, it may still mask significant compositional effects. There is some indication that turnout changes are favouring a more pro-European demographic (many of which did not vote in 2016). As opinion polls do not explicitly incorporate the turnout dimension in 2016, we know very little about that demographic that is set to bear most of the legacy cost of Brexit – which, in the end, still makes up around 30% of the UK electorate.

The below plots changes in turnout across 140 councils for which data has been available at the time of writing. This incomplete data suggests that changes in turnout between 2019 and 2014 benefited the explicitly pro-Remain parties and much less so the hard-Brexit supporting parties.

Figure 5: Changes in the 2014 and 2019 EP turnout

This is an observation that appears to hold true across Europe: turnout increases seem associated with the weaker than expected performance of populists across the board. That this pattern is driven by an increase in mobilization among remain-minded voters relative to leave-minded voters becomes clear when looking at opinion polls that study turnout intentions around the 2014 EP elections vis-à-vis turnout intentions in 2019. Most polls conducted prior to 2014 suggest that 66% of UKIP supporters indicated that they would definitely vote – this compares to 53%, 52%, and 47% among the Conservative, Labour, and Liberal Democrat voters). In 2019, there are much more balanced turnout intensions among the Leave and Remain groups.

This is an observation that appears to hold true across Europe: turnout increases seem associated with the weaker than expected performance of populists across the board. That this pattern is driven by an increase in mobilization among remain-minded voters relative to leave-minded voters becomes clear when looking at opinion polls that study turnout intentions around the 2014 EP elections vis-à-vis turnout intentions in 2019. Most polls conducted prior to 2014 suggest that 66% of UKIP supporters indicated that they would definitely vote – this compares to 53%, 52%, and 47% among the Conservative, Labour, and Liberal Democrat voters). In 2019, there are much more balanced turnout intensions among the Leave and Remain groups.

This highlights that the swing to Remain that became apparent in the 2019 elections is, to a significant part, driven by the increased mobilization of Remain-minded voters many of whom were absent from the polls in 2014 (and, to a significant extent, also in 2016). Similarly, there was significantly less mobilization of former UKIP-turned-Leave supporters compared to 2014, which simply reflects the fact that a sizable chunk of Leave supporters voted Leave (and UKIP) as a protest vote – in 2014, 26% of all UKIP voters stated that they voted UKIP ‘to send a message or as a protest vote’, while only 43% stated they support UKIP to strengthen the case of the UK leaving the European Union.

While the No Deal Brexit parties may have won the 2019 EP elections in terms of seats, the clear winner was actually the explicitly pro-Remain parties, which just appears more distributed across a set of parties. What is even more remarkable is that the electoral losses of Labour and the Conservatives appear to not be aligned across the Leave versus Remain dimension that the 2016 referendum revealed. This highlights that the established parties could gain by clearly positioning themselves on the future of Brexit – though it appears that a Conservative Party endorsement of a No Deal Brexit could clearly put it on the losing side. The elephant in the room, however, is how the UK’s electoral system would skew and turn such a result on its head.

______________

About the Author

Thiemo Fetzer is an Associate Professor in the Economics department at the University of Warwick.

Thiemo Fetzer is an Associate Professor in the Economics department at the University of Warwick.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.