COVID-19 is putting unprecedented pressure on European healthcare systems. Tamara Popic draws together some early lessons, arguing that the crisis should prompt a rethink of the direction of healthcare policies across Europe, and that the principle of solidarity must now move to the forefront as countries seek to mitigate the impact of the outbreak.

COVID-19 is putting unprecedented pressure on European healthcare systems. Tamara Popic draws together some early lessons, arguing that the crisis should prompt a rethink of the direction of healthcare policies across Europe, and that the principle of solidarity must now move to the forefront as countries seek to mitigate the impact of the outbreak.

The spread of COVID-19 has put new pressures on already strained national health systems across Europe. In Italy, the country reporting the highest number of deaths linked to the virus in Europe so far, hospitals are facing severe crises trying to deliver the necessary care, while doctors are making heart-breaking decisions on how to distribute scarce resources. The usual stereotypes of Italian dysfunctionality notwithstanding, the 2018 Bloomberg ranking of the countries with the most efficient healthcare systems around the world places Italy fourth. The Italian population also ranks as the second healthiest population in the world. As one of the most efficient health systems and one of the healthiest populations in the world is struggling under the pressure, there are at least two lessons that could already be learned from the present crisis.

All that glitters is not gold

First, European governments should re-think the direction they have pursued with their healthcare policies over recent decades. A breakdown of coronavirus risk by demographic factors shows that those most likely to die are the old and the sick, population groups most dependent on the public healthcare system. Yet, European health systems in 2020 are less public than they were 30 or even 10 years ago. The logic behind these developments, guided by the New Public Management approach, has been that scaling down of the public sector would make health systems more efficient and responsive to the population’s needs.

The consequence of this approach has been a slow but steady reduction of public spending for healthcare. OECD Health Data show that since 1990 public spending as a share of the total spending for healthcare has decreased in most European countries. In some countries in Eastern Europe the decline has been even higher than 30 per cent.

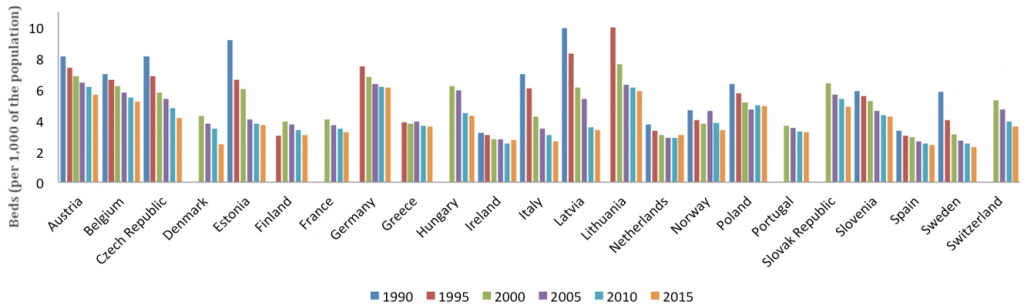

While this trend has produced a variety of effects, a reduction of hospital capacity is one of the most important. As hospitals deliver costly specialised care and as European hospitals are still predominantly public hospitals, one of the key cost-containment measures has been to reduce the number of hospital beds. The figure below shows there has been a significant decline in curative hospital beds since 1990 across the whole of Europe (with the notable exception of Finland). In Italy, the number of beds per 1,000 people declined from 7 in 1990 to 2.6 in 2015. The tragedy is that these beds are now among the most needed elements of healthcare system capacity in the context of the present crisis.

Figure: Curative (acute) hospital beds per 1,000 of the population (1990-2015)

Source: OECD Health Data 2019

A call for solidarity

Second, the current crisis underscores the key principle of public healthcare – solidarity. A reduction of public spending for healthcare across Europe was paralleled with a series of policy measures that involved privatisation and the introduction of market-like instruments in the provision of medical care. In the hospital sector, these measures involved the privatisation of hospital beds and changes in the model of hospital ownership, including transformation of public hospitals into private-for-profit hospitals and joint-stock companies. The logic, similar to the one applied to reductions in public funding, has been that replacement of the public sector led by the state with private and competitive, market-oriented care provision would make health systems more efficient and responsive.

However, research shows that these types of policy changes have contributed to the creation of two-tiered healthcare systems. In this kind of system, access to necessary care is dependent on one’s capacity to pay for it and solidarity granted by the public system is eroded. And this is happening at a time when the general trend in inequality has spared neither our health nor our health systems, as countries face persistent inequalities in health and in access to healthcare services.

If these developments were not worrying enough, then the current health crisis caused by the coronavirus demonstrates that solidarity matters now more than ever. A quick look at the United States reminds us that having universal access to care is key in responding to the present crisis. News that the UK’s NHS will use private beds for virus sufferers may have seemed encouraging at first, but the subsequent announcement that private hospitals will be charging the NHS £300 per bed suggests that solidarity risks disappearing at the time when it’s most needed. Having resilient, well-funded public health systems with universal access to healthcare is key not only for solidarity, but also for national if not global salvation. It’s time to come together.

_________________

Note: This article was first published on LSE EUROPP. Featured image credit: Marcelo Leal on Unsplash.

Tamara Popic is a Research Fellow at the Max Weber Programme of the European University Institute.

Tamara Popic is a Research Fellow at the Max Weber Programme of the European University Institute.

But should we be judging the number of hospital beds we need by a crisis that occurred not because of the shortage of hospital beds but because preventive, primary care and public health systems failed? The key breakdown has been – to use a hackneyed metaphor – “the fence at the top of the cliff” not the ambulance at the bottom. If we build ore hospital beds, these will inevitably suck resources from prevention and public health