The EU and the UK have yet to reach an agreement on their future relationship, but if an agreement is reached, will it be possible to ratify the deal before the transition period expires at the end of 2020? Nicolai von Ondarza and Dominik Rehbaum look at the role of the European Parliament in previous trade agreements, concluding that a deal will likely have to be done by mid-November at the latest.

The EU and the UK have yet to reach an agreement on their future relationship, but if an agreement is reached, will it be possible to ratify the deal before the transition period expires at the end of 2020? Nicolai von Ondarza and Dominik Rehbaum look at the role of the European Parliament in previous trade agreements, concluding that a deal will likely have to be done by mid-November at the latest.

The negotiations on the future relationship between the EU and the UK are nearing crunch time. In order to avoid a ‘no trade deal Brexit’, an agreement must enter into force by the end of 2020 when the current transition period expires. Most recently, Boris Johnson set mid-October as a deadline to reach a deal. But how much time is there really left to negotiate? One crucial aspect of judging this is the amount of time needed to scrutinise and approve an agreement by the European Parliament, even if both sides manage to strike a deal.

The European Parliament as the ‘bad cop’

The framework of the negotiation process is eerily similar to the Brexit drama of 2019: although the UK has left the EU in an orderly fashion, the major questions of the future trade relationship remain unanswered. If the deadline of 31 December 2020 passes without a new agreement, the UK will leave the transition period without a new cooperation regime with the EU in place. Four months before the end of the transition period, both sides remain far apart on core issues such as the level playing field, state aid and fisheries, with very tough negotiations ahead. But when exactly will the negotiators have to overcome the stalemate and broker compromises to avoid a ‘no trade deal Brexit’?

In order to gauge the remaining time, we can look at the steps that are needed once an agreement is struck. Formally, any agreement(s) must be fully translated into legal text and then, like the Withdrawal Agreement, get the consent from both the European Parliament and the EU Council. Incidentally, this time around the UK House of Commons is not required to consent to the future relationship agreement(s). The EU Council can approve such an agreement within a few days, but the length of time required for the European Parliament is a more unknown quantity.

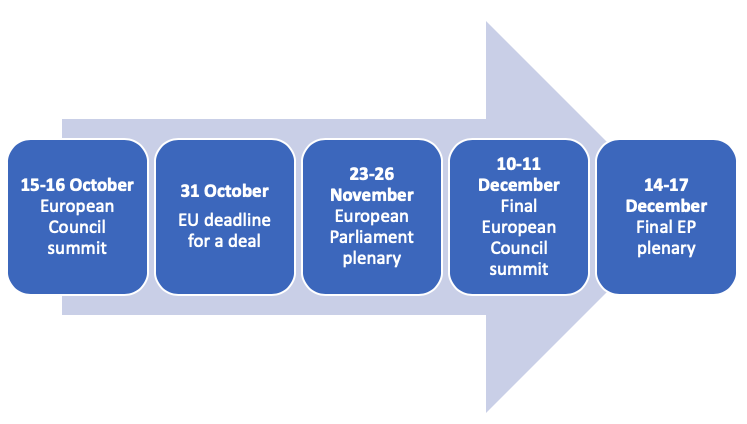

Figure: Timeline for the Brexit negotiations

Credit: UK in a Changing Europe

First, looking at the Article 50 negotiations suggests that the EP is likely to play a supportive role. Unlike the House of Commons, which was the centre stage for much political drama in the UK and rejected the proposed Withdrawal Agreement three times, the majority of MEPs generally backed the EU negotiators around Michel Barnier. In six resolutions over the last four years, the Parliament underlined the major aims of the EU in the Article 50 negotiations – in particular, the safeguarding of citizen’s rights, the UK commitments to the EU budget and keeping the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland open. It also threatened to vote down any agreement that disrespects these principles. Thus, it played the role of a ‘bad cop’ to Michel Barnier, who could point to the EP’s red lines in addition to the European Council mandate when negotiating with his UK counterparts.

When the time came to consent to the Withdrawal Agreement, however, the European Parliament was satisfied and demonstrated its capabilities for swift action. After the Withdrawal Agreement Bill finally passed both House of the UK Parliament and gained royal assent on 23 January 2020 after almost a year of political struggle, the EP conducted its consent procedure within six days, including an approval by 621 to 49 and an emotional ‘Goodbye’ to (most) of the UK MEPs on 29 January. If willing and its demands are met, the EP can give its consent within the space of a couple of days.

The pace of democracy

In the Political Declaration that accompanied the Withdrawal Agreement, the EU and the UK agreed to ‘develop an ambitious, wide-ranging and balanced economic partnership’ for their future trade relations. While the Withdrawal Agreement represented an absolute novelty for the EU, negotiating a trade agreement with the UK puts the Union right on its home turf. The Lisbon Treaty anchored international trade matters as an exclusive competence of the EU. Furthermore, the treaty established that the EP’s consent is necessary before the Union can enter into trade agreements – including a potential trade agreement with the UK.

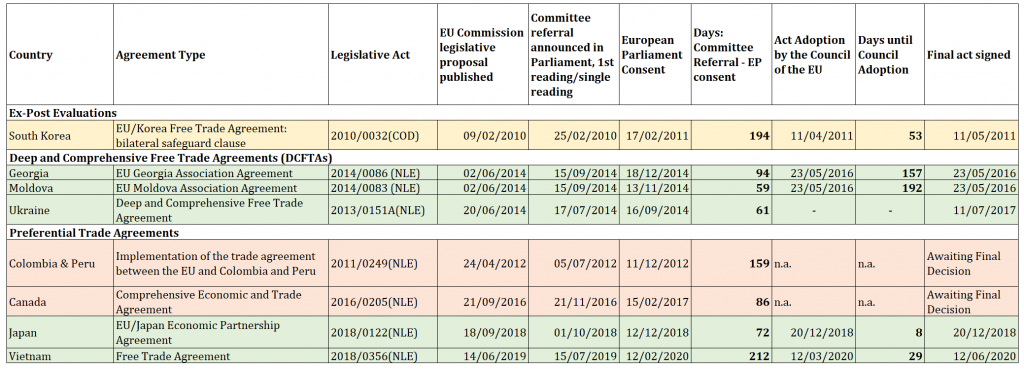

Table: The European Parliament’s role in ratifying trade agreements

Note: Compiled by the authors.

Since the 2009 treaty changes, the European Parliament has consented to eight trade agreements. Not least due to their variance in scope, depth and their distinct political context, there is no blueprint for the duration of the EP’s consent procedure. It requires MEPs to scrutinise the agreement in the relevant committee(s) and negotiate a joint position within their national delegations and their party groups. Trade agreements such as CETA have, in the past, led to significant disagreements within party groups such as the Socialists and Democrats (S&D).

On average, this process in the EP lasted about 117 days. However, the Parliament demonstrated in the case of its Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with Ukraine and CETA with Canada that it can act swiftly when required and give consent within just two months. What is more, there does not seem to be a direct correlation between the length of a trade agreement, its political salience and the duration of the parliamentary procedure. While 61 days should not be mistaken as the absolute minimum amount of time for the parliament’s consent, this nonetheless demonstrates that parliamentary processes are to a certain degree lengthy and require coordination and debate.

Finally, it should be kept in mind that in the case of the Ukraine DCFTA and CETA, trade negotiations had lasted for six plus years already with only a few controversial issues left on the table. The current Brexit negotiations are nowhere near a similarly promising stage with no consensus on a legal text in sight. It is therefore unlikely that the European Parliament will grant consent much quicker than in the past and thus the situation points to a lengthier consent procedure than on the Withdrawal Agreement.

Conclusions

With the clock once again ticking in the Brexit negotiations, the last parliamentary session is scheduled for 17 December 2020. After analysing the lengths of previous legislative procedures on preceding trade agreements, it is evident that the final legal text of the agreement needs to be agreed by mid-November at the latest in order to provide the European Parliament with enough time for thorough scrutiny of the draft. The examples both of the Withdrawal Agreement and previous free trade agreements suggest that the EP can act quickly even on politically contentious dossiers, but any agreement after mid-November would be a serious risk.

A further complication is that unlike both previous trade agreements and the Withdrawal Agreement, just four months before an agreement should enter into force there is not even a joint draft in sight. The UK after Brexit will become one of the EU’s most important trading partners, and thus the potential EU-UK free trade agreement will be a cornerstone agreement for the Union and the UK alike. This will require proper scrutiny, and thus at least a month’s time in the European Parliament.

_________________________________

Note: The above was first published on LSE EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: CC BY 4.0: © European Union 2020 – Source: EP.

Nicolai von Ondarza is Head of the EU/Europe Research Division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

Nicolai von Ondarza is Head of the EU/Europe Research Division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

Dominik Rehbaum is an Assistant in the EU/Europe Research Division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

Dominik Rehbaum is an Assistant in the EU/Europe Research Division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).