Most referendums ask voters whether they want to join a political project. Britain’s EU referendum did the opposite. Elliott Green argues the campaigning was suffused by appeals to nostalgia and to a past in which Britain “took control”. He identifies four groups of voters to whom this message appealed: imperialist nostalgists; racists; non-racist and non-imperialist nationalists; older voters.

Most referendums ask voters whether they want to join a political project. Britain’s EU referendum did the opposite. Elliott Green argues the campaigning was suffused by appeals to nostalgia and to a past in which Britain “took control”. He identifies four groups of voters to whom this message appealed: imperialist nostalgists; racists; non-racist and non-imperialist nationalists; older voters.

Now the dust has settled a bit on last month’s vote, we should reflect on the deep conflicts it revealed about sort of nation the UK’s people would like it to be. One little-noted fact is that the referendum asked voters about leaving or retreating from a political project. Most referendums do the opposite. The vast majority of modern national referendums are about undertaking a new project, whether joining the EU, approving a new constitution or constitutional amendments, becoming a republic or an independent state. In these cases, the referendums invited countries to take a step forward into a new future – one in which life would be better than it had been before.

In contrast, the Brexit vote was a choice between the status quo or returning to what the UK looked like before it joined the European Community in 1973. This was a very rare example of giving voters an option to go back to the past, rather than the future, and it was explicitly sold as such by the Leave campaign. The common phrase used by Brexit supporters was “take back control” (in addition to “take control”), with an implicit appeal to the idea of returning the UK to what it looked like before it joined the EU Boris Johnson similarly talked about the UK’s “loss of sovereignty,” with the implicit idea that the UK’s sovereignty would be “regained” if voters chose to leave the EU. Nigel Farage also campaigned on the slogan that “we want our country back” – again, yet another clear call for returning to an unmentioned, halcyon past before the UK was overloaded by EU bureaucracy and European immigrants.

Far from appealing solely to a narrow group of anti-EU activists, these calls for returning to the past were directed at a variety of voters – in particular four overlapping groups of people:

1) Imperialist nostalgists. In 1973, the UK had only recently given up its Empire and still clung on to some of its smaller colonies like Belize and Hong Kong. The memory of the imperial past was quite fresh. Indeed, in the 1975 referendum to confirm Britain’s membership in the then European Economic Community, one of the major No campaigners was Enoch Powell, famous not only for his “Rivers of Blood” speech but also for his earlier ambitions to become Viceroy of India, while other No supporters argued that the UK should focus on its links with the post-imperial Commonwealth, rather than Europe. This nostalgia is still present today among the Brexit supporters, and it is not specific to the UK: the right-wing Austrian Freedom Party, for instance, has arguably drawn upon imperial nostalgia, as have Marine Le Pen and the Front National in France.

2) Racists. A huge amount of ink has already been spilt on how anti-immigrant racism contributed to the Leave victory, and one can easily see how invoking a Britain before mass immigration would encourage people to vote for leaving the EU. Indeed, the sharp rise in racist attacks after the referendum has included shouts of “make Britain white again,” despite the fact that leaving the EU will probably see a rise, not a fall, in non-white immigrants to the UK. Here again, there is nothing specifically British in this regard: just take a look across the Atlantic to Donald Trump, whose rise to power has been built largely on the support of white Americans with racist, anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim attitudes, and whose major catchphrase is ‘Make America Great Again,’ not ‘Make America Great’.

3) Non-racist and non-imperialist nationalists. Scholars of nationalism such as Anthony Smith have long pointed out that nationalists commonly believe in the concept of a ‘golden age’ of the nation, such that their goal is to return their nation to its glorious past and revive it from its slumber. In many cases this ‘golden age’ is often set in the ancient past, but it need not be so distant. Indeed, for many British nationalists the golden age is World War II, when the UK resisted the Nazis and won a bloody war over great odds. Of course, World War II has long featured as a major feature in British national identity, and thus it was not surprising that references to the war featured prominently in the Leave campaign. Indeed, many Brexit supporters, including one 81-year old woman whom I met before the vote, cited Britain’s ability to ‘go it alone’ in World War II as a reason why it could survive outside the EU today, while others such as Boris Johnson compared the EU to Hitler and Napoleon.

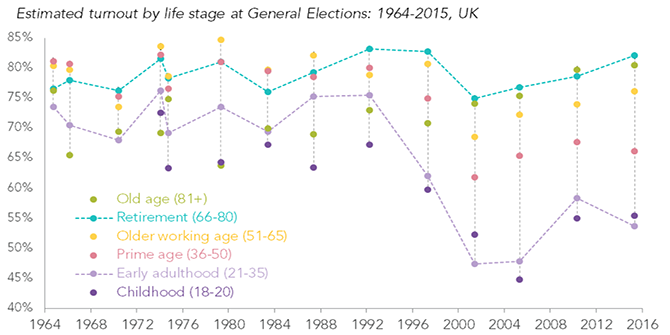

4) Older voters. The Brexit referendum exposed a generational split in the UK. Age was one of the most important correlates of voting for Leave. What was surprising about this support for Brexit among older voters was that, in general, they tend to be risk averse as regards political change. However, in this instance they had a rare chance to vote to return to the UK of yesteryear, which in some cases certainly provoked nostalgia not only for what the UK looked like before 1973 but also what they themselves looked like. Mixing up happy memories of one’s youth with memories of society as whole is not uncommon: in one study conducted among elderly Roma in Bulgaria and Hungarians in Romania, the former group had much less attachment to the past on both a general and a personal level. Arguably, this difference lies in the fact that Romanian Hungarians can look back positively to a period when they were still part of Hungary and not an ethnic minority in another country, while the Roma have no comparable happy past to recall. This last point can also help to explain at least part of the strong support for the Remain camp in Northern Ireland and Scotland, inasmuch as the period prior to 1973 evokes the Troubles for the former and a period before devolution and the discovery of North Sea oil for the latter.

The one silver lining in this analysis is that, if another referendum were to be held again but with different wording, it is likely that the UK would vote differently. More specifically, if the question posed was not one of leaving the EU and implicitly returning the UK to what it looked like in 1973, but instead asked voters’ opinions about the specifics of the UK’s relationship with the EU going forward, then appeals to history would be much less salient. Whether or not there is a second vote on Brexit, one hopes that future referendums will be worded in such a way that encourages voters to think more about the future than the past.

____

This post was originally published on the Brexit blog.

Elliott Green is Associate Professor of Development Studies in the Department of International Development at the LSE.

Elliott Green is Associate Professor of Development Studies in the Department of International Development at the LSE.

Older people, certainly anyone over the age of 40 would have made their minds up about the EU quite some time before the referendum.

It’s easy to claim there are people who have emotive motives to leave the EU, but the same could be said of *some* people who want to remain.

I believe it would be difficult to get any kind of concensous on people’s motives….sometimes for a laugh I tell people that I voted to leave because I could really do with a 1300 watt hoover!

My mind was made up with Black Wednesday. After that, I despaired when listining to middle-class students tell me that the Euro is a fantastic idea because there’s no changing currencies faff if we was in the Euro.

There’s a complete disconnect.

A while back, I was on a JSA training day to help us get a job.

The trainer was stood there telling us that the EU is great because we can get a job in Europe.

I mean, he’s talking to a bunch of unskilled, semi-skilled people who have families and littel qualifications. What hope do they have competing with millions of unemployed people in Europe? To get what kind of a job, that pays what kind of money?

What about EU grants being used by companies to close up in the UK and relocate to Eastern Europe where costs are lower?

How can you expect people on a zero-hours and minimum wage to be pleased that the EU is all about supressing their wages and taxing them so that they pay for the relocation of their own job to continental Europe, while the middle-class young tell them that the EU is great because they have fun in their gap year?

People are crying themselves to sleep. They believe most of the middle-classes and the rich absolutely hate them and enjoy seeing them living in such misery. It’s like the hunger games.

In defence of the older voter…

In 1975 I also voted Leave.

This was largely because this was the prevailing view amongst the history and economics academic staff, which strongly influenced me. There always seems to be a prevailing fashion in academia doesn’t there?

However in 1975 most of my student contempories, and indeed the rest of the country begged to differ.

Yet 40 years on it seems our generation has largely changed its mind.

Nostalgia?

Not really. Try disenchantment with Brussels self serving power grabbing, imposing one bad pork barrel policy after another, which are impossible to reverse through the democratic process..

And from Maastricht onwards both the denial of promised referenda to transfer further powers, and the manipulative overturning of lost ones This surely removed any last semblance of democratic legitimacy in many peoples’ eyes?

And finally the virtual coup d’erats in Greece and Italy of legitimately elected governments.

No alternative. I voted for my granddaughter to inherit a democratic country. Somewhere where the popular vote both changes the government and the policies it pushes.

Maybe a better word would be “experience?” Yes, you can’t beat historical experience to add context.

This was a decision about our future, made in a large part by people looking firmly backwards. Today is in 2016 but this poor preparation for the ramping up if the fourth industrial revolution. We are stronger inside the third largest trading bloc on the planet than as an irrelevant island. Remember the brain drain from the seventies? You’ve just voted for an even bigger one as our young reject this nationalistic madness.

“The one silver lining in this analysis is that, if another referendum were to be held again but with different wording, it is likely that the UK would vote differently. More specifically, if the question posed was not one of leaving the EU and implicitly returning the UK to what it looked like in 1973, but instead asked voters’ opinions about the specifics of the UK’s relationship with the EU going forward, then appeals to history would be much less salient. Whether or not there is a second vote on Brexit, one hopes that future referendums will be worded in such a way that encourages voters to think more about the future than the past.”

Definitely there are lessons to learn from Brexit, especially in terms of political communication. Back in February, I advocated much in line with your conclusion warning that referendum was not the right format for the issue addressed and if opted for it, then (a) the question should be correctly formulated to escape narrow framing and instead broadening the perspective and forward-looking; and (b) the plebiscite to be postponed (say, until March 2017) and a proper consultation and civic education campaign organised by the Government (through a body representative of both camps but also independent experts) to explain to citizens what might be the realistically forecast consequences of either choice so that they would be in good position to make informed decision and not being mislead by false expectation (on either side). One of possible outcomes of this deliberative process well might have been the rejection of the very idea of holding referendum and instead finding some other way to address Britain’s concerns with regards to EU membership and think of solution to many real-life problems which are not necessarily the outcome of EU failures but for which the domestic political system shall take responsibility.

…’and a proper consultation and civic education campaign organised by the Government (through a body representative of both camps but also independent experts) to explain to citizens what might be the realistically forecast consequences of either choice’. So they will Vote the way the Government want them to; in this case, vote to stay in the EU. Still; hopefully the deed is done.

First, the government was divided over the issue, and therefore ‘what Government wants’ doesn’t stand for any position in this case. Second, the Government had called for referendum and therefore it is its job to ensure the quality of the outcome (meaning that people are aware of the issue and consequences for both the outcomes–independently of what they choose to vote for).

‘What the government wanted’ was very clear during the referendum campaign, with the PM, the Chancellor, and about three-quarters of the Cabinet campaigning for Remain. Those few ministers campaigning for Leave were clearly putting their jobs at risk, for the future if not immediately. Believing that the Government saw its responsibility being to ensure the quality of the outcome in the terms you describe it is frankly naive- in fact the Government tried very hard to ensure that a particular outcome eventuated, not anything about its quality. I would guess, comical though this now seems, that even the timing of the referendum was probably chosen by the Government to maximise the chances of a Remain result.

Given the outcome and its aftermath, maintaining a faith in ‘independent experts’ also seems odd. The IMF has already had to admit, to its embarrassment, that its predictions regarding the short-term results were wrong. Maybe, given their directorate, they aren’t independent though they seemed to masquerade as such pre- referendum.

Personally, I think that the genuine role of experts in a referendum is to choose the wording to be fair, and then to slug it out on either side without the pretence of independence.

In another 41 years time you can have another referendum and the god news for Remoaners is that they would then get to play the nostalgia card. Maybe the slogan wil be ‘take undemocratic beurocacy back’ and hark back to the bygone age when electorates never had to bother their pretty little heads about any serious issues as these were handled by technocrats.

If any Remoaners doubt their future prospects on such a premise, maybe it indicates that Leave won this time for good reasons that have nothing to do with nostalgia or emotional arguments. Fact is that the Remain campaign relied on Fear rather than any rationale arguments for a superstate, and since Project Fear is already a busted flush they won’t even have that in the unlikely event there is any 3rd UK referendum on EU membership.

I’m surprised you couldn’t include two further groups of voters in those to whom Brexit appealed- the idealists and the realists.

The *idealists* can see that the arrangements for democracy in the EU, are very poor; were designed as such by those who did not trust their own electorates; have shown no improvement in 50 years; and are structurally immovable. They know that the only way to a demcratically- functioning EU is to dismantle it and start again.

The *realists* can see that creating a common-currency area without massive flows of money to the poorer-performing zones was economically illiterate, and dooms it to initial underperformance, then total failure. They believe that not participating in the Euro only distances the UK to a small extent from the forthcoming Euro-smash, and that Brexit gives the. UK a little more distance from the future financial fall-out.

You’ve claimed here that the EU’s system of decision-making is “structurally immovable” and has “shown no improvement in 50 years” despite the fact that the legislative process is radically different today than it was 50 years ago. The European Parliament was a non-factor 50 years ago, now it’s a co-decision maker in the vast majority of areas. QMV didn’t exist 50 years ago, now it’s a necessity in getting things done in many cases.

I also can’t for the life of me see why “dismantling” the EU and starting again is a better route than reforming it. How on earth would that work in practice? And what exactly would this new democratic system involve in precise terms (what would the specific decision-making process be, what institutions would exist, how would decisions be made, etc.) We only ever seem to discuss these issues in vague terms (soundbites about the EU disrespecting electorates, general moaning) but if the EU’s system is wildly undemocratic, as you imply, then propose an alternative.

The EU Parliament continues in its itinerant path and is now allowed to send an observer when the grown-ups are conducting negotiations. On the one occasion it exerted itself slightly in the direction of trying to rein in the corruption in the Commission, the Commission showed their cotempt for us all by appointing an innumerate windbag with no business experience, no finance experience, and no accounts experience, to investigate its own financial shortcomings. Have the EU accounts been signed off for last year? Thought not. QMV was just the minimum change to prevent a total logjam due to the increase in the number ofcountries involved. I understand that people in countries with corrupt governments may be accustomed to this, but that does not excuse it.

Why dismantle the EU? Let’s look at its record. Fisheries: When the EU had finished raping the fisheries arond Europe they proceeded to do the same around Africa. Why did Iceland withdraw its application for EU membership? EU Agriculture: who is that a succes for, do you think? EU foreign policy: failure in the Ukraine, failure in the Balkans, failure in Syria. The Euro: ill conceived and causiing untold misery for a whole generation, mainly in Southern Europe. I could go on.

To build a democratic Set of institutions needs a democratic mandate across all the countries involved. It needs to be built, brick by brick, so we grow together, and high- handed actions like destroying Greece to defend the Euro,is just the opposite of what we need.

Do we want the return the UK to what it looked like in 1973? No; it’s 2016. No; we just wanted out of the EU. Something that some people fail to grasp.