Has political science generally failed to fulfill its broader social responsibilities in terms of cultivating political understanding and stimulating engaged citizenship? asks Matt Flinders. The increasing evidence of political disaffection stems from the existence of an ever-increasing “expectations gap” between what is promised/expected and what can realistically be achieved/delivered by politicians and democratic states.

Has political science generally failed to fulfill its broader social responsibilities in terms of cultivating political understanding and stimulating engaged citizenship? asks Matt Flinders. The increasing evidence of political disaffection stems from the existence of an ever-increasing “expectations gap” between what is promised/expected and what can realistically be achieved/delivered by politicians and democratic states.

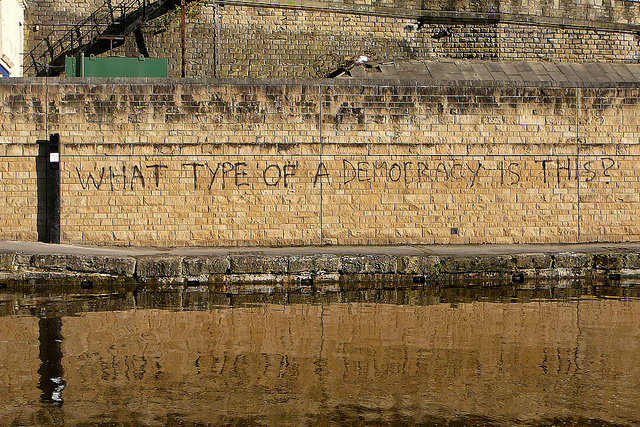

If the twentieth century witnessed “the triumph of democracy” then the twenty-first century appears wedded to “the failure of democracy” as citizens around the world (setting recent developments in North Africa and the Middle East aside for the moment) appear to have become distrustful of politicians, sceptical about democratic institutions, and disillusioned about the capacity of democratic politics to resolve pressing social concerns.

Even the most cursory glance along the spines of the books on the library shelves reveal a set of post-millennium titles that hardly engender confidence that all is well (Disaffected Democracies; Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices; Political Disaffection in Contemporary Democracies; Hatred of Democracy; Why We Hate Politics; Democratic Deficit; Vanishing Voters; Democracy in Retreat; Uncontrollable Societies of Disaffected Individuals; etc.). And yet if democracy is in crisis then it must be said that this has been the dominant narrative for at least half a century. “Is democracy in crisis?” provided the opening line of the Trilateral Commission’s 1975 report into evidence of growing dissatisfaction among the public with political processes, political institutions, and politicians. The “civic culture” so endeared by Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba had somehow mutated into a “critical culture” with parallel pessimism about the future of democracy.

In contextual terms the social and political fabric has changed arguably beyond contention in the last half-century. The decline of deference, increasing levels of education, growing levels of mobility in all its forms, the existence and perception of “new” social risks, an increasingly aggressive media, the impact of ever more immediate and sophisticated forms of communication technology, the influence of three decades of neoliberal dominance have all, in their own ways, increased the demands on democratic political systems.

And yet the pressures created by the changing context have not generally been matched by related increases in the capacity of democratic governance to deliver. The rise of globalized networks, the transition from “government to governance,” declining levels of social capital, and a host of other factors have arguably combined to ensure that the conclusion of the Trilateral Commission’s 1975 report—The Crisis of Democracy—that “[t]he demands on democratic government grow, while the capacity of democratic government stagnates” continues to hit a contemporary chord.

The nature of political rule has changed in ways that have generally made the business of government more difficult. This has implications for both the politics and management of public expectations, on the one hand, and for public attitudes toward political processes and institutions, on the other, which scholars have generally been slow to acknowledge.

The Politics and Management of Public Expectations

Lying beneath a focus on the changing nature of political rule is therefore a deeper and more basic question concerning the nature of public expectations vis-à-vis democratic politics. My argument here is both bold and sweeping: the politics and management of the public’s expectations (regarding lifestyle, health care, education, pensions, travel, food, water, finances, the environment, etc.) will define the twenty-first century.

Let me explain this argument by reference to a simple model. Imagine for a moment two horizontal bars placed one above the other with a significant gap between them. The upper bar relates to demand and specifically to the promises that politicians may have made in order to be elected (in addition to the public’s expectations of what politics and the state could and should deliver). The bottom bar relates to supply in terms of what the political system can realistically deliver given the complexity of the challenges, the contradictory nature of many requests, and the resources with which it can seek to satisfy demand. The distance between the two bars is therefore an “expectations gap” and recent survey evidence seems to suggest that in recent years the expectations gap has widened. With this simple framework in mind my argument is straightforward: The increasing evidence of political disaffection stems from the existence of an ever-increasing “expectations gap” between what is promised/expected and what can realistically be achieved/delivered by politicians and democratic states.

Three short observations before moving to the final question. First and foremost, the analysis of public expectations regarding public services and the capacity of politicians appears to represent something of a terra incognita for political science. Mass data banks and survey results provide rich data about the state of public attitudes but provides far less in terms of why the public hold such views or exactly how their expectations have been shaped, let alone the theories and methods through which political science can generate more sophisticated insights. My argument here is not in line with advice of Bernard Baruch about “voting for the man who promises the least as he’ll be least disappointing” but it does begin to open fresh questions about whether democracy really is failing or if society is simply expecting too much. “If we understood politics rather better,” Colin Hay argues in his award-winning Why We Hate Politics (2007), “we would expect less of it. Consequently, we would be surprised and dismayed rather less often by its repeated failures to live up to our over-inflated and unrealistic expectations.”

Political Science and Society

A focus on the politics and management of public expectations vis-à-vis democratic politics brings us to the hook, or the barb, or the twist in this commentary and a questioning of the role of political science itself within the demos. The Trilateral Commission of the 1970s went to great lengths to highlight the intrinsic challenges to the functioning of democracy by which it meant the simple fact that democratic government is not perfect, it does not operate in an automatically self-sustaining or self-correcting fashion, and mechanisms must be put in place, and constantly reviewed, to prevent the abuse of power.

A more subtle intrinsic challenge lies in the straightforward observation that politics (and therefore politicians) is tasked with squeezing collective decisions out of multiple and competing interests and demands (as Gerry Stoker argues in his excellent book Why Politics Matters). The political process is therefore inevitably based on compromise, negotiation, and incremental adjustment—Max Weber’s “strong and slow boring of hard boards”—for the simple reason that there are no simple solutions to complex problems. My question here relates to whether political scientists have some form of professional responsibility to the public to stimulate public understanding and debate about the existence of these intrinsic features and how they play out in relation to a myriad of issues and questions as a counterweight to unrealistic (or what Weber labeled “infantile”) expectations. Put slightly differently, whether political science might play a valuable role in closing “the expectations gap” or at the very least playing a more visible role in public debates.

“Politics is the master science, both as an activity and as a study,” Bernard Crick wrote, “[but] neither the activity nor the study can exist apart from each other.” In making this point Crick sought to highlight a link between the health of democratic politics and the health of the study of politics. A quarter of a century later Samuel Huntington would use his Presidential Address to the American Political Science Association to reemphasize this link in his argument, “Where democracy is strong, political science is strong … where democracy is weak, political science is weak.” In making this point Crick and Huntington were attempting to expose the deeper social purpose of political science in the sense of cultivating public understanding and promoting engaged citizenship by daring to emphasize the inescapable moral dimension of politics in both theory and practice. In doing so Huntington quoted Albert Hirshman’s adage, “Morality belongs [at] the center of our work; and it can get there only if social scientists are morally alive and make themselves vulnerable to moral concerns—then they will produce morally significant works, consciously or otherwise.”

Political scientists possess a professional obligation not just to each other in terms of disseminating their research findings but also to the wider public in terms of explaining why their research matters (i.e., why it is relevant) as a contribution to cultivating active citizenship and political literacy. The discipline must therefore learn to “talk to multiple publics in multiple ways”—to adopt Michael Burawoy’s phrase—in order to not only increase the visibility and leverage of the discipline among potential research funders or to improve levels of public debate and understanding about pressing political issues but also to improve the overall standard of scholarship.

This is a critical point. As Michael Billig argues in his Learn to Write Badly (2013) not only has the general standard of writing deteriorated in the social and political sciences but scholars also deploy verbose terminology in order to exaggerate, conceal, and succeed. Bernard Crick highlighted and warned against exactly this trend in his “Rallying Cry to the University Professors of Politics” and his complaint about “all the author’s chaff on everything before ever the grain is reached.” My point here is that presenting and testing the findings of research beyond the lecture theatre and seminar room or writing for a public audience offers great potential in terms of stress-testing ideas, assumptions, and conclusions. Moreover, in relation to the analysis and understanding of whether democracy really is in crisis such a model of “engaged scholarship” may also play a small—but no less important—role in closing the gap that appears to have emerged between the governors and the governed.

A longer version of this article appears in the latest issue of Governance and is entitled “Explaining Democratic Disaffection: Closing the Expectations Gap”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Politics and Founding Director of the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. He is the co-author of the international journal Policy & Politics and is Visiting Distinguished Professor in the Sir Walter Murdoch School of Public Policy and International Affairs at Murdoch University, Western Australia. His books include Multi-Level Governance (coedited, 2004), Democratic Drift (2008), Walking without Order (2009), The Oxford Handbook of British Politics (coedited, 2010), and Defending Politics (2012) (all Oxford University Press).

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Politics and Founding Director of the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. He is the co-author of the international journal Policy & Politics and is Visiting Distinguished Professor in the Sir Walter Murdoch School of Public Policy and International Affairs at Murdoch University, Western Australia. His books include Multi-Level Governance (coedited, 2004), Democratic Drift (2008), Walking without Order (2009), The Oxford Handbook of British Politics (coedited, 2010), and Defending Politics (2012) (all Oxford University Press).