In the course of a year and a half, Labour Party membership has increased massively. The number of full members has moved from 190,000 in May 2015 to 515,000 in July 2016 – an influx of 325,000 new members. Monica Poletti, Tim Bale and Paul Webb explore how we can explain the pro-Corbyn surge in this growth.

As part of our ESRC-funded Party Members Project (PMP), we fielded a first survey with existing Labour members in May 2015 and a second one with post-election members in May 2016. We now know that at the most recent leadership election those who were members before May 2015 voted predominantly for Owen Smith, whereas the new members opted mainly for Jeremy Corbyn. This prompts a key question: in what respects did the ‘new’ members differ from the ‘old’ members?

In order to find out, we compare these two groups: older members (pre-GE2015) and newer members (who joined after May 2015 but before January 2016 and were therefore eligible to vote in the leadership election). A number of features stand out: gender; left-wing identity; social liberalism; campaign activism; feelings about the leadership; and the possibility that the ranks of the newer members, and those that support Jeremy Corbyn, may have been swollen by what we call ‘educated left-behinds’ – people who, given their qualifications, might have been expecting to earn more than they currently do.

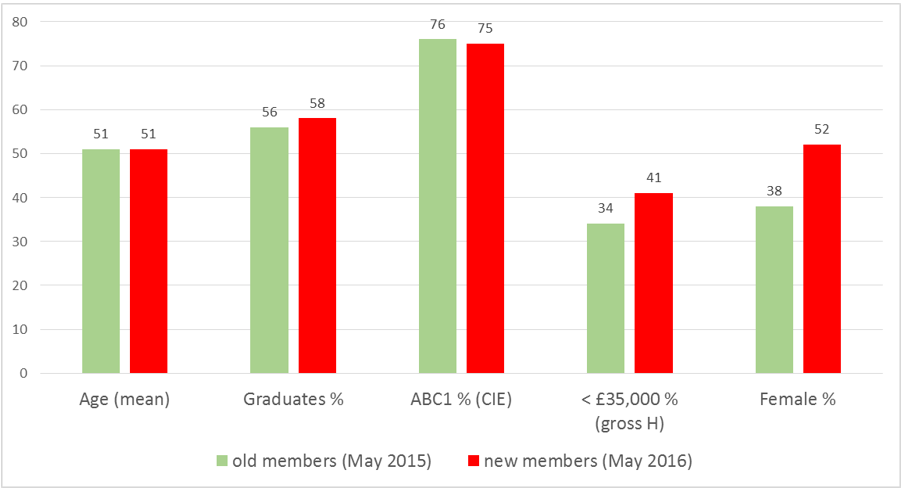

Slightly less well off – and a lot more women

First up, we find that new members are not significantly younger or more working class – but they are more likely to be slightly less well-off and female. The average age of both old and new members is 51 and more than half of them are graduates (56% and 58% respectively). Whereas three quarters of them live in households in which the chief income earner (CIE) has a ‘middle class’ (ABC1) occupation (76% vs. 75%), a third (34%) of old members’ household gross income falls below the national average of around £35,000 –something that’s the case for 41% of new members. Moreover, women make up a greater proportion of the new members than of the older members (52% to 38%). Corbyn, then, does not seem to have attracted a very different type of crowd in many socio-demographic respects, except insofar as it is slightly less well-off and more gender-balanced.

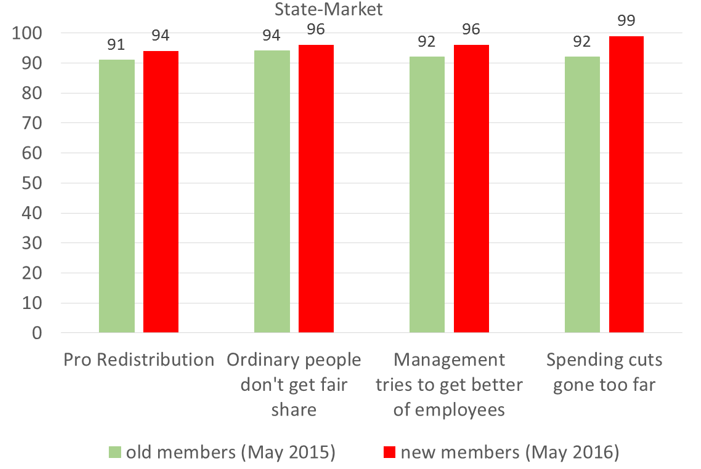

No necessarily more left wing – although some of them think they are

New members are certainly not very different from the old members when it comes to their views on the state vs the market. The overwhelming majority of members are pretty left wing, whether they joined prior to the 2015 GE or after: they are pro-redistribution (91% vs 94%), believe that ordinary people do not get a fair share (94% vs. 96%), think that the management tries to get the better of employees (92% vs. 96%) and think that spending cuts have gone too far (92% vs. 99%).

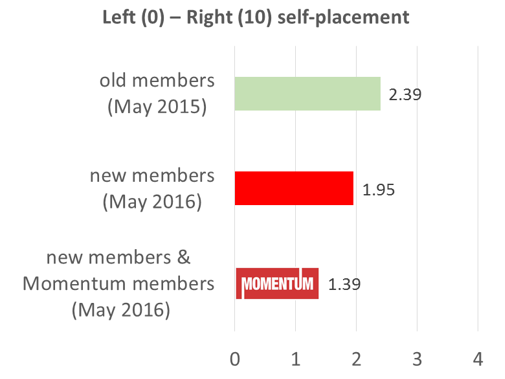

They do, however, self-position differently on a left (0) – right (10) scale, with new members seeing themselves as significantly more left-wing (1.95) than older members (2.39). And if we isolate only Momentum members (10%), this difference is even more accentuated, given that they self-locate a full point further to the left than older members (1.39). Thus, in terms of subjective self-image, which probably embraces more than just state-market opinions, the new members see themselves as something of a leftist vanguard.

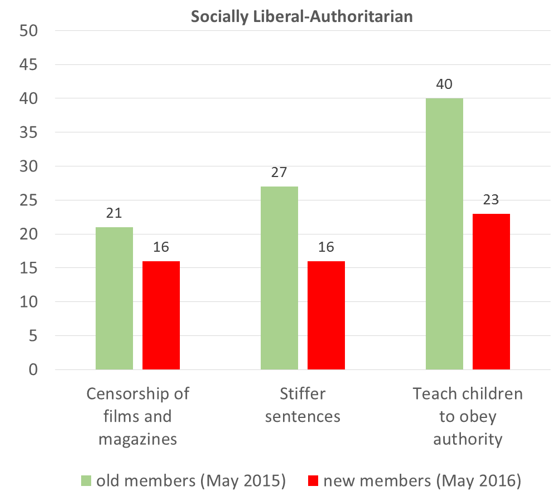

They are decidedly more socially liberal

New members are, in fact, decidedly more socially liberal than older ones on a few central issues: they are considerably less keen than old members on introducing censorship of films and magazines (16% vs. 21%), stiffer sentences (16% vs 27%) or teaching children to obey authority (23% vs 40%).

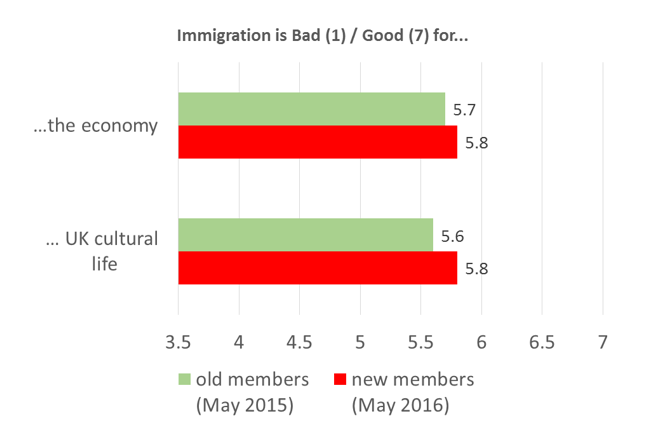

The two groups seem, however, to have similar positions on considering immigration a good thing for the economy (5.7 vs. 5.8 on a scale running from bad (1) to good (7)) and for the UK’s cultural life (5.6 vs. 5.8).

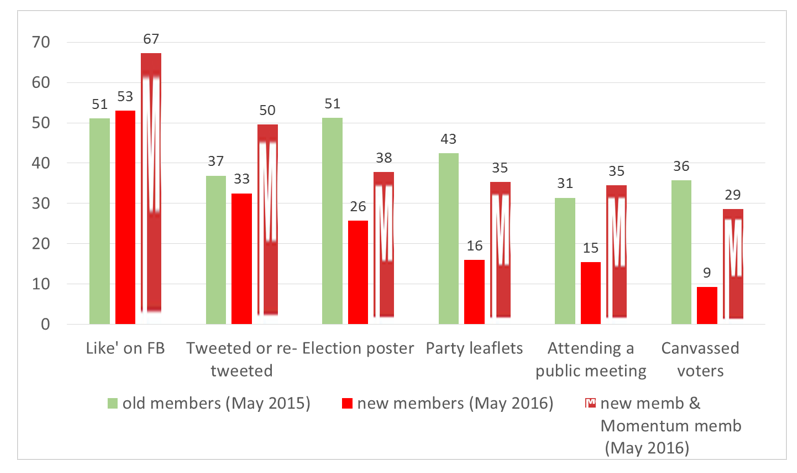

More likely to restrict their activism to online clicktivism

Old and new members tend to participate similarly in online political activity: (Facebook 51% vs. 53%; Twitter 37% vs 33%). When it comes to offline participation, however, there is a striking difference: new members are plainly not as keen to get stuck in. While a third (31%) of the old members attended a public meeting during the GE campaign, less than a sixth of new members did so during the campaign for the 2016 local/regional/mayoral elections (15%). Although less was presumably at stake in 2016 than 2015, an even wider gap is registered when looking at activities such as leafletting (42.5% vs. 16%), displaying election posters (51% vs 26%) or – most notably of all – canvassing voters (35.7% vs 9.3%). The preference for clicktivism over other forms of activity, however, is much less pronounced for those who are Momentum members. Although these people do tend to participate more in online activities than everybody else (Facebook 67%; Twitter 50%), the gap with older members’ participation in offline activities is much smaller (displaying election posters 38%, leafletting 35%, canvassing voters 29%); indeed, Momentum members were actually more likely than old members to have attended public meetings (35%).

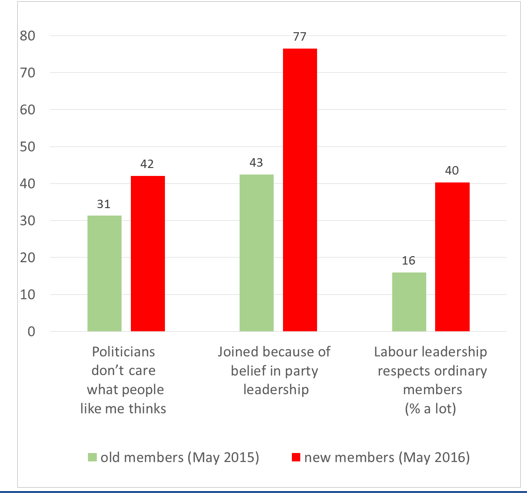

Feel more respected by the leadership

Whereas the new members are more likely to believe in general terms that politicians don’t care what people like them think (42% vs. 31%), they are much happier with what they’re getting from the Labour leadership than members in 2015. Not only did three quarters of them join the party because of belief in the party leadership (76.5%), as opposed to only 42.5% of old members – the difference between Corbyn and Miliband (and his predecessors). They are also much more inclined to believe than those we surveyed back in 2015 that the Labour leadership respects ordinary members (40.3% vs. 16%).

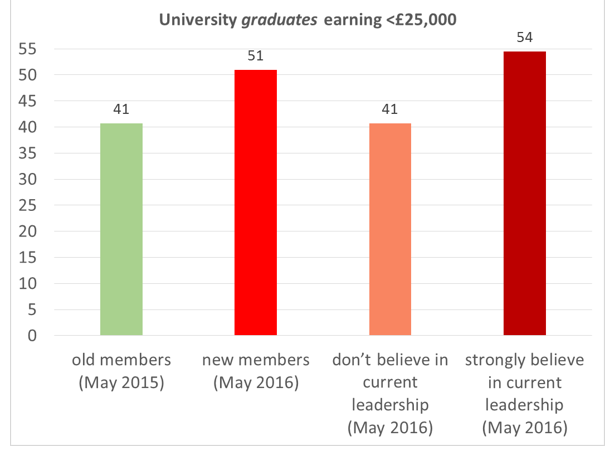

They are more likely to be ‘educated left behinds’

Relative deprivation theory suggests that people tend to make comparisons between what they expect out of life and what they actually experience, looking at people who are rather similar to themselves for cues as to what to expect. Thus, university graduates tend to derive their expectations from looking at other graduates and risk frustration if these expectations are not met. Did a sense of relative deprivation trigger some graduates to join Labour in the hope that the Corbyn leadership would help render their actual economic conditions closer to their professional expectations? Possibly so. The proportion of graduates among Labour members earning less than the average salary (around £25,000) is 10 points higher among new members than among older ones (51% vs. 41%). And a considerable gap also exists between pro- (54%) and anti- (41%) Corbyn new members.

In short, the Corbyn leadership has attracted similar people in terms of age, education and occupational class to those who were Labour members in 2015, although new members are slightly less well-off and more gender balanced than the past. New members are similarly left-wing on the state-market dimension, although they are more likely to regard themselves as further left and are certainly somewhat more socially liberal than older members. Although they tend to participate mainly online and not so much offline, this is less true for those who are also members of Momentum. Clearly, the new members are confident that the new leadership respects them and this is something that distinguishes Corbyn from most other politicians in their eyes. Finally, there is some evidence that the educated left-behinds might have been particularly moved to place new hope in Corbyn. How long they keep the faith, and what that means for the Labour Party, remains to be seen.

—

Note: This blog is based on research from the ESRC Party Members Project: https://esrcpartymembersproject.org/, @ESRCPtyMembers, partymembersproject@gmail.com

Monica Poletti is an ESRC Post-Doctoral Fellow in Politics working on the ESRC Party Members Project (PMP) at Queen Mary University of London, a Guest Teacher at the London School of Economics and a Research Fellow of the COST-Action ‘True European Voter (TEV)‘ project.”

Monica Poletti is an ESRC Post-Doctoral Fellow in Politics working on the ESRC Party Members Project (PMP) at Queen Mary University of London, a Guest Teacher at the London School of Economics and a Research Fellow of the COST-Action ‘True European Voter (TEV)‘ project.”

Tim Bale is Professor of Politics in the School of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary, University of London.

Tim Bale is Professor of Politics in the School of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary, University of London.

Paul Webb is Professor of Politics at the University of Sussex.

Paul Webb is Professor of Politics at the University of Sussex.

The gains achieved by the Labour movement, have increasingly been taken for granted, and still are to a significant extent, especially in more affluent parts of the country. When ordinary people vote Tory it is because they wrongly believe it is in their interest to do so. When things go wrong and life gets tough, people no longer see ‘politics’ as providing solutions. Politicians are seen as individuals who seek to get elected for our own ends, and think we will do or say anything in order to further our careers. Cornyn is seen differently, even by those who do not like or agree with him. That is his greatest strength, and what makes him eminently electable! People now have a choice – the old refrain ‘they are all the same’ has died away. That was part of the politics of the past, we need to move on and embrace this change.

Three things for me initially, recognising:

Overt exploitation of workers through things such as zero hour contracts (affecting my kids)

Continued reduction of services such as NHS and and infrastructure (housing and transport) and the extortion of fees for things that have previously been funded (university) again affecting the next generation

The reality that there was no real material difference between Conservstives and Labour. And both sets of MPs offered me nothing to believe in.

Until Jeremy Corbyn started talking about things I recognised from 35 years ago. Fairness, investment in people and infrastructure, public housing.

Since then I have watched as career politicians from all sides have undermined this approach to politics and the renewed social engagement it has engendered.

The most striking thing I have noticed though is that when you look for, when you realise it is there, it how clear the bias is in the main stream media. The BBC panders to the Conservatives and ukip and prefers to interview PLP MPs less tolerant of Corbyn. The press continually undermines the rising Labour Party.

Your point about clicktivism is very true. I am guilty of this. I am happy to fund and to do my bit 121 with friends but I haven’t yet truly done my bit canvassing. Too busy? Intimidated about the prospect? Don’t consider it important to me? I haven’t yet reconciled it to myself yet. But I do know that what I currently do is not enough.

In terms of sustainability of new members the awareness that the right wing of the party is awaiting our boredom and ultimately our withdrawal is playing

to my contrariness. I will continue to support the socialist element of a party that is returning to its roots and its initial purpose. Defending the rights of workers and those less fortunate. This return of the Labour Party has been a bright spot in otherwise very dark times for many people.

excellent piece of work – if only the mainstream media would use it to dispel the myths and, more important, the PLP read and digest its potential – Corbyn’s support is not the mythical bunch of infiltrators; it clearly has a demographic mix which a united party could develop into an election winning vote if the anti- Corbyn politicians actually bought into what this shows. I live in hope.

I joined when Miliband became leader as he talked socialism, well at least suggested he was left. I have voted Labour for nigh on 50 years. Only now do I feel the leadership has any idea how big a change we need

I am a new member. I was elected CLP delegate, attend every meeting. Branch and CLP. Out canvassing and also acted as auditor. I have felt welcome and mentored. My blog here about why I joined. Lessons for new and old members. The word Hope figures largely for me. More Unites. Members at least. https://tishnaught.wordpress.com

As someone with more education than salary might I suggest that it might not be simply ‘left behinds’ but ‘stay behinds’? Some of us lack conventional economic aspirations – to a degree- and/or are ambivalent about the degree of separation from original social groups that economic ‘success’ tends to imply.

In my area the majority of ‘new’ ‘members seemed to be people who had at some time been members who had resigned or defected over such as Iraq war etc & who had become members again

Barry mirrors my instant thought – did the research include identifying how many of the ‘new’ members were returning old members who left during 1997 – 2010?

I think it is obvious that the membership rose to support the popular Leadership Candidate Jeremy Corbyn and that more joined to vote for him the second time around.

Previously, many supported Ed Milliband as he gave the impression he was leading towards the lef – I was inspired by his stance regarding the ‘Bedroom Tax’ as it appeared to be grossly unfair to so many. When he stepped down there wasn’t a suitable replacement candidate.

I now support Jeremy Corbyn as Leader and admire his integrity.

There is much analysis but it doesn’t cover ‘Socialism’ as the main reason for Corbyn’s support – the PLP has not been strong on that element and that is why division is occurring.

I haven’t joined the Labour Party for any selfish reason, I am more concerned with protecting the vulnerable and maintaining our Rights gained, which seem to be threatened at this time.

The problem for Labour is electability as under Corbyn party policies is now mapped closely on what members want. Members are a narrow cohort that is unrepresentative of the public at large. Witness the around 15% advantage in polls for the Conservatives and the vote for BREXIT. The largest single group that voted ‘out’ were the poor in the regions and the main issue was on immigration which Labour sees as no problem but a plus.i.e..over 50% voted against immigration. Western economic policies and politics are driving rising populism in the US and Europe with nearly half of adults today are Authoritarian Populists https://www.buzzfeed.com/albertonardelli/extreme-views-are-becoming-the-mainstream-in-britain-and-eur?utm_term=.xsWnodGD9#.ts3pmYOxw. Inequality can only rise as the global rich own the Western economic and political system so populism will rise in parallel i.e. further from Labour politics.

It’s a specious argument to pretend that the public will come round to Labour thinking because the conservative cohort has a very different view of what constitutes reality. . Political persuasion is defined by personality type (see Haidt). Very few conservatives will change their personality type to embrace today’s Labour policies in a world that increasingly threatens their values..

This is not a problem so long as Labour sees itself as a party of protest rather than of Government.

Although not a scientific poll, or even a flood of support, but we campaign in the main street every Friday and I am surprised at the amount of Tory voters that want to join Labour to support Jeremy Corbyn and like what he has to say, conversely they hate what the Tory Party has become.

Interesting. If this study continues then it would be interesting to learn members’ attitudes to the EU and the reasons for it, e.g. opposed to EU because it’s a bosses club/ because of immigration/??; pro-EU because of social chapter/ freedom of movement/??

And whether members want Brexit to happen: yes/no to Hard Brexit, yes/no to soft Brexit, no Brexit; want a referendum on the terms &c &c

I struggle to understand the Party’s EU policy given that the leadership and most MPs were Remain supporters. Have they been converted to Brexit? Were they always Leavers (“the bosses’ EU”) and have now come out of the closet? Is it purely electoral in that most face Leave voting majorities in their constituencies? Do they sincerely believe that the June vote on the idea of Brexit has settled the question irrespective of what plan is eventually produced? Or is there a subtle long game where they wait for their chance – perhaps when public opinion swings against Theresa May’s Brexit – and they can say to their Leave voters “We tried to make it work, but we can’t, so let’s Remain after all”?

If we knew more about what the membership thought we might get more of a handle on the Leadership’s approach

Michael

Facebook: Campaign for the Real Referendum on the Terms of Brexit

How many of the “new” members are actually old members returning to the arty because they saw the opportunity to stop the the party veering to the right. most labour mp’s would be better described as centre right rather than left wing politicians.