Posted by Patrick Dunleavy.

Posted by Patrick Dunleavy.

The Liberal Democrat surge puts us into new territory in forecasting how the 2010 Parliament will look. However, things work out from now on, it seems much less likely that David Cameron can command an overall Commons majority. His best outcome may now be a ‘shallow hung Parliament’, with the Tories as the largest party but no majority for legislation – which might lead to a second general election as early as May 2011.

Instead, the odds have dramatically shortened on a “deeply hung“ Parliament. And here the analysis is not as simple as you might think. A great deal depends on two key thresholds:

- Which of the Conservatives or Labour has the most MPs – this is key for which has the moral right to be the first to try and form a government.

- Whether Gordon Brown has to leave Downing Street because he cannot realistically stay on as PM, or whether he could in principle try for a coalition govenrment.

If Brown just does sufficiently well that Labour plus Liberal Democrat MPs could form a majority government between them, then as the incumbent PM he legitimately can try to form a coalition government, or to govern as a minority government with Liberal Democrat agreement. He only needs to resign if this bid fails.

Brown’s case is made stronger here by the fact that Labour has done a lot of preparation for a coalition and has a lot to offer the Liberal Democrats, whereas David Cameron has done nothing to prepare for a hung Parliament. But if the Tories have most MPs, this puts Nick Clegg in a difficult situation, especially since the Tories will almost certainly have more votes in the electorate than Labour.

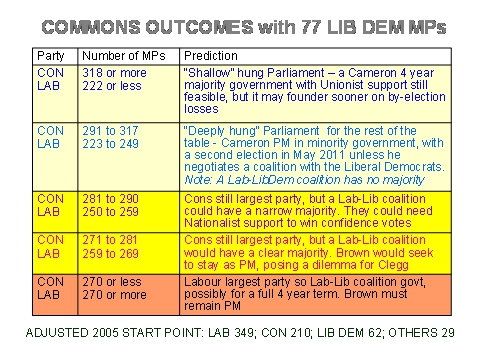

Suppose the Liberal Democrats get 77 MPs

To see how these possibilities work out, I consider a pretty conservative estimate of the consequences of the current polls, which assumes that the Liberal Democrat surge dies away a good deal by polling day (perhaps getting 25-27 per cent support in the final vote) but that they still do well enough to get another 15 MPs.

The pie chart below shows what this means for the two main parties. There are 650 MPs in total, but 18 of these are for Northern Ireland (a completely different party system) and I assume that 15 will be won by the Nationalist parties in Scotland and Wales and a scattering of independents. With 77 Liberal Democrats that means that the combined 3rd, 4th, 5th and smaller parties would have 110 MPs between them.

That leaves only 540 seats for Labour and the Tories to split between them, and the Table below shows how their changing balance of seats would usher in different hung Parliament scenarios. Once the Tories fall into a zone with 280 to 318 MPs, then we are into a “shallow hung Parliament” where the Tories would be the largest party, and Labour and the Liberal Democrats could not form a majority coalition government.

Once Tory MPs drop below 281 seats then a Lab-LibDem coalition could begin to govern with a majority, and once Labour reaches 260 MPs such a government would be able to survive confidence votes. When Labour gets to 270 MPs (highly likely on this scenario) then Gordon Brown would have an unchallenged right to stay in Downing Street and to either form a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats (which could have a full four year term) or soldier on as a minority government (which would be very difficult indeed)

Once Tory MPs drop below 281 seats then a Lab-LibDem coalition could begin to govern with a majority, and once Labour reaches 260 MPs such a government would be able to survive confidence votes. When Labour gets to 270 MPs (highly likely on this scenario) then Gordon Brown would have an unchallenged right to stay in Downing Street and to either form a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats (which could have a full four year term) or soldier on as a minority government (which would be very difficult indeed)

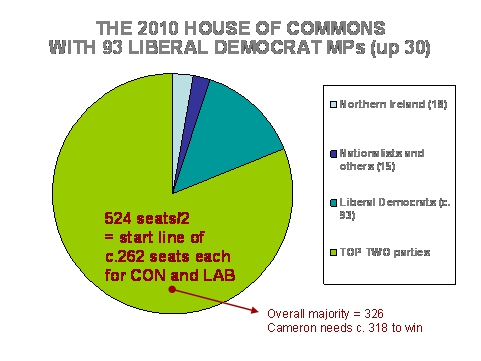

Now suppose the Liberal Democrats do brilliantly and get 93 MPs

If the Liberal Democrat surge does not die away but continues on at full force until polling day, they will still find it surprisingly hard to win MPs – because the electoral geography works against their relatively even spread of support across the country.

Suppose however that Clegg’s wave can somehow break this problem – which might happen, since many bets are now off. A realistic top ambition would then be for the Liberal Democrats to get 93 MPs – improving their current tally of 63 MPs by winning another 30 new constituencies. Again the pie chart below shows that this would further reduce the number of MPs that the Conservatives and Labour could share between them – to just 524 seats.

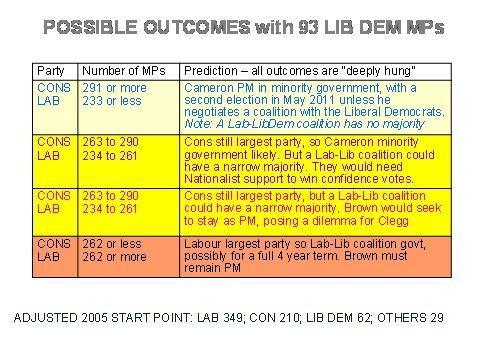

The Table below now shows that only “deeply hung” Parliament scenarios are now foreseeable. In theory Cameron could still lead a minority government, but the Conservatives would need to gain more than 90 seats from Labour to do so – a very hard to achieve objective with Liberal Democrat support riding high, unless the Labour vote should collapse in some way not seen so far. Even for Cameron to be clearly the largest party might be difficult, because Labour should still win many more MPs per million votes than the Tories will.

The Table below now shows that only “deeply hung” Parliament scenarios are now foreseeable. In theory Cameron could still lead a minority government, but the Conservatives would need to gain more than 90 seats from Labour to do so – a very hard to achieve objective with Liberal Democrat support riding high, unless the Labour vote should collapse in some way not seen so far. Even for Cameron to be clearly the largest party might be difficult, because Labour should still win many more MPs per million votes than the Tories will.

If Labour can stem its losses to less than 87, Gordon Brown would lead the largest party in this House of Commons and would need to negotiate a coalition with the newly numerous Liberal Democrats, and would have a strong incentive to do so in order to avoid the risks and perils of a minority government. In which case the many commentators who have written him off and pronounced the death of ‘new Labour’ may suddenly need to revise their views, and constitutional reform in the UK would be back on the agenda with a bang.

If Labour can stem its losses to less than 87, Gordon Brown would lead the largest party in this House of Commons and would need to negotiate a coalition with the newly numerous Liberal Democrats, and would have a strong incentive to do so in order to avoid the risks and perils of a minority government. In which case the many commentators who have written him off and pronounced the death of ‘new Labour’ may suddenly need to revise their views, and constitutional reform in the UK would be back on the agenda with a bang.

I blame the changes in the way we teach History in schools for all this confusion. When I was a lad we was told Britannia ruled the waves and the mother of parliaments was the best and fairest system known to man what was ever invented by God. Maybe if we can all suspend our disbelief again instead of hanging our parliament, we can all carry on the same road as we did fifty years ago, when England was great, the ruling class ruled with an iron hand and everybody that wasn’t happy could shut up or get locked up, as is only right and proper in a civilised country.

Hello! Here in my butcher’s shop in Smolensk, where Yuri, my assistant is today find out if intestines of cat make decent tripes substitute, we are remark similarities of away goals rule in Champion’s League of Footballs and strange first past the post electoral system in UK.

For those of you who unsure about away goals rule, here is explanations. Away goal is count for double. That is, one goal is equal two. So, imagine game in semi-final of Champion’s League between hated Dynamo Kiev and Spartak Moscow. (Stranger things have happen. My mother once saw a levitating horse in Irkutsk.) In first leg, play in Kiev, Spartak is have great start, score 4 goals in first half. These are count for 2. To get back on level term, Kiev is need score 8, which in blistering display of attacking verve, they do. So, score, which look like 8-4 to Kiev, is in reality 8-8. Spartak is only need score one goal in home leg, and they go through 5-8, which in reality is 9-8. (Yuri is look me scepticals now, but I sure right.)

First past post system is many analogies with above situations. There are 650 constituency in UK. So to win election, it is need have won 326. Now, if ruling party is win 326 seat, but is only do so by be one vote ahead nearest party in each seat (let us call this third party, for reasons become apparent), then this create interesting tensions. If second party win most of remaining seats, again by 1 vote over third place party, but ruling party is get no vote at all in second party seats, it possible do very well in popular vote, even have highest votes, and have no seats, while possible win election with pitiful small vote.

So, in this case, like in Champion’s League, some votes is count even more than doubles. Indeed, when compared with third party vote and seats gained, you may express as equation in which 326 is divide by 0, which make one vote INFINITELY powerful.

So, we are make suggestions. If party which win in above scenario is so ingenious in mobilise support, it should be given powers in proportion to power of it vote, that is to say, infinite powers. This allow unpopular but clever governments win elections, while still operate within longstanding British tradition of democratic accountability and fairness.

We seem to give no thought to the pernicious long-term effects of having, mandate after mandate, governments enjoying support of only 25% of the electorate, and when the shape of coalition government looms on the horizon we dismiss it with the phrase “hung parliament” with all the troubling implications of the word “hung”. How is it that so many democracies can live quite happily with coalition government, where one party’s programme is not imposed on the electorate willy-nilly, but where each initiative has to find common support across the ruling parties’ spectrum? Measures that are adopted have a better chance of being properly implemented if the support base is wide. And the politicians do what they should do, namely discuss policies throughout the mandate before adopting measures that achieve sufficient broad political support across the governing parties.